L'edicola digitale delle riviste italiane di arte e cultura contemporanea

Flash Art Int. (1999 - 2001) Anno 34 Numero 216 January-February 2001

Aperto Albania

Edi Muka

Franz Ackermann

Wolf-Günter Thiel and Milena Nikolova

n. 216 Jan-Feb 2001

Shangai Biennale

Satoru Nagoya

n. 216 January-February 2001

Cecily Brown and Odili Donald Odita

n. 215 November-December 2000

Cai Guo-Qiang

Evelyne Jouanno

n. 215 November-December 2000

Aperto New York

Grady T. Turner

n. 213 summer 2000

Sexually Explicit Art

Grady T. Turner

n. 212 May-June 2000

Albania is a state of mind, a metaphor for space, and a rite of passage. As represented by media and politics, Albania runs the risk of turning into nothing but a site of migration: a shelter for the refugees from Kosovo or a point of no return in the escape towards the Western myth. Albania lives the tragedy of distance: its citizens are close to everything and everyone (NATO, the U.N., Italy, the East...), yet they are forced to leave their homeland, and rely only on the image of a future which never happens.

Escape or hope: this is how we picture a better tomorrow. This precarious equilibrium, a hybrid of desire and frustration, often produces a cynical optimism, or generates a feeling of melancholy and uselessness in the face of history.

Albanian artists are reflecting the tragedy of the present, while trying to escape from it: they are walking a tightrope stretched between brutality and comedy, between documentary and metaphors. Theirs is a struggle to articulate new forms and languages in order to come to terms with utopia.

It can't be just a coincidence that three of the most interesting Albanian artists don't live here anymore. Having experienced diaspora and the fall of political and social powers, they have nowhere to return and no unitary style or language with which to express themselves. Albanian art in fact relies on a variety of media and stylistic solutions. We learnt not to trust unity and systems: we prefer accepting heterogeneity and diversity as the only reliable truths.

Videos, documentaries, films, and performances are all interchangeable tools that Albanian artists exploit in order to grasp the complexity of their situation: they document reality and yet they keep their distance.

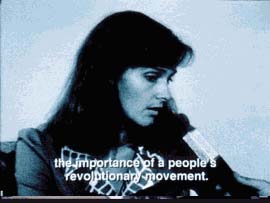

A subtle mistrust towards reality and fiction seems to pervade all videos and films by Anri Sala, who moved to Paris in 1997. Anri Sala belongs to a generation of young artists that received their education after the change of the political system in Albania: a generation that grew up in a communist country and, all of a sudden, had to experience the trauma of capitalism without even enjoying its advantages. From this ideological schizophrenia, Anri Sala has learnt to push the language of documentary to its radical conclusions, working on the borders between reality and absurdity. In Intervista, Finding The Words (1997), his first film, the artist forces his mother to watch an old b/w talk show in which she had appeared as a representative of the communist party. There is no soundtrack to the old found footage, and the artist has to rely on reading his mother's lips in order to reconstruct the dialogues and the slogans pronounced by her. The mother and her son sit in front of the TV set, each trying to shape their own version of the past: she can't admit she had spoken those words, and yet her son has the responsibility of discovering the truth about his family and his country. What we witness in Intervista, Finding The Words is an exercise in interpretation, an effort to bridge the distance between past and present: a story that unravels in a multiplicity of gazes, which neutralize the sense of objectivity traditionally associated with documentaries.

Anri Sala's more recent Nocturnes adopts the same, fragmented narrative, built up with a series of interviews and other visual tropes mediated from the rhetorics of television. Nocturnes is a metaphor for the Balkanian situation, as narrated by a mercenary and by an obsessive collector of fish and aquariums: without ever directly mentioning the words Albania or Kosovo or Serbia, the two characters talk about cruelty and borders, animals and human beings, killing and surviving. In their descriptions, history and geography become slippery territories, bound to endless negotiations: a perennial struggle between truth and desire, fiction and autobiography.

Autobiography is also the starting point of Adrian Paci's work. In 1997, a tragic year for Albania, Paci left his home and moved to Italy, together with his wife and two daughters, leaving behind a country which was on the edge of a civil war.

This experience left a deep trace in Paci's life and family: art became a luxury and all his energies were invested in the very basic task of survival. It was only after having built a new life for himself and his family, that Paci could return to art: he started painting again, but soon realized that he could not possibly compress all his experiences in such a static medium. The idea for his first video came almost accidentally, simply by listening to his three year-old daughter as she told a fairy tale about her escape from Albania, and about her family's fears and hopes. Paci decided to turn the camera on and create a spontaneous ready made, which is far from being yet another intellectual commentary on the status of art. Paci's video, in fact, simply records an innocent, childish game, in which magical animals and funny creatures live in a mythical world populated by soldiers and multinational forces, in a painful synthesis of infantile cosmography and brutal actuality. Shot in a basic, almost primitive style, Paci's video is not just a desperate and moving story: it also takes a critical stand on the manipulative power of international and local media, and their applications in the representation of Albanian culture. Incidentally, Paci's video ended up in the hands of Italian Police, who arrested the artist under the suspicion of producing child pornography. He was interrogated and asked to prove his status as an artist; all of which was video taped at the police station. Afterwards, Paci asked for a copy of the tape, and converted the whole experience into an art piece entitled Believe Me I'm An Artist.

The stereotype of Albania as a land of abuse, violence, and criminals, is reflected in the work of Sislej Xhafa, one of the most established Albanian contemporary artists. Born in the city of Peja, in Kossovo, Xhafa moved to Italy several years ago, and he began to pave his way through the contemporary art scene. But Xhafa's work relies on a continuous friction between cultures: it needs conflicts and negotiations, and that's why Xhafa recently decided to move to New York, turning again into a stranger in a stranger land. In fact, Xhafa's art has become like an exercise in turning weaknesses into strengths: he draws from the controversial imaginary associated with his culture, in order to compose a portrait of the artist as clandestine. All his interventions are carried out with the violence of a criminal act, piling up poor materials such as wood and newspapers, or, on the other hand, mixing cheap jewellery and expensive furniture in a crass imitation of a wealthy, gangster-like lifestyle. As a perfect clandestine, Xhafa doesn't possess any language that he can claim, but he can easily move from one context to another, working in the background, contaminating styles and idioms: photos, videos, objects and performances can all become part of Xhafa's complex and often gigantic installations, or they can be used in a more discrete way, on the verge of the invisible, when the artist decides to disappear and mingle with reality. So you might happen to stumble onto one of his performances without even noticing; maybe when you are on your way to the office or to your summer house, which is what happened to some tourists and commuters at the train station in Lubljiana, Slovenia, where the artist, perfectly dressed up in a black suit, improvised a stock exchange auction just in front of the billboard that usually announces the departures and the arrivals of trains.

Caught in his personal stock exchange frenzy, Xhafa treats people and trains as nothing but shares, numbers, statistics, turning his performance into a sarcastic comment on the burden of bureaucracy, with all its mathematical precision and visas, special permissions and procedures. Bureaucracy is the target of another public installation by Xhafa, built in Ghent on the occasion of the exhibition "Over the Edges." Xhafa transformed the lobby of the local police station into a top class hotel, bringing in carpets, couches, crystal lamps, liquors, and giant Louis XIV mirrors, while classical music played in the background. In this purgatory de luxe, criminals and clandestine immigrants were given a last chance at experiencing a cheap mirage of wealth and success, before being taken away to prison or sent back to their home land. While Xhafa is trying to transform negative stereotypes into a new form of the urban guerrilla, Erzen Shkololli (one of the youngest and most interesting artists still active in Kosovo) works with the local rituals and folklore. His pieces are built with wool and fabrics taken from national costumes and flags, and then reassembled in patchworks and installations. Shkololli acts as a sort of instinctive and biased anthropologist: he re-enacts traditional ceremonies, while insinuating contemporary symbols and disillusions. It's this indecision between past and present that makes Shkololli's work a typical example of what it means to work in the Balkans today: we suffer from a tragic form of ideological strabismus, and we are lost between tradition and modernity, remembrance and hope, freedom and death.

Edi Muka is a critic and curator based in Tirana.