| |

|

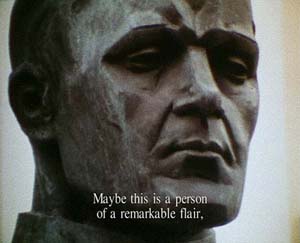

Deimantas Narkevicius, ''Countryman''. Courtesy Galleria Continua S.Gimignano

Deimantas Narkevicius, ''Countryman''. Courtesy Galleria Continua S.Gimignano

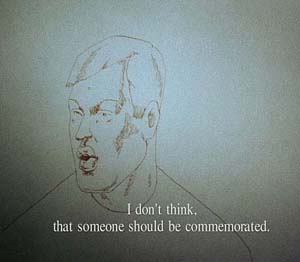

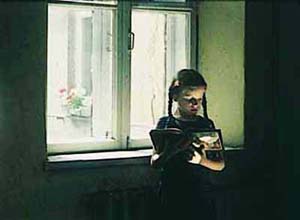

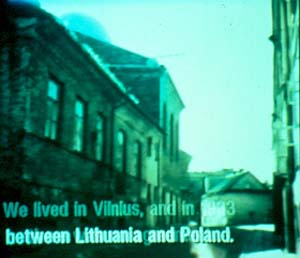

Deimantas Narkevicius: ''Legend coming true'' , 1999. Super 8 mm film on to Betacam SP, 68 min.

Deimantas Narkevicius: ''Legend coming true'' , 1999. Super 8 mm film on to Betacam SP, 68 min.

Deimantas Narkevicius: ''Legend coming true'' , 1999. Super 8 mm film on to Betacam SP, 68 min.

Deimantas Narkevicius: ''Legend coming true'' , 1999. Super 8 mm film on to Betacam SP, 68 min.

Deimantas Narkevicius: ''Legend coming true'' , 1999. Super 8 mm film on to Betacam SP, 68 min.

Deimantas Narkevicius: Energy Lithuania, 2000. Super 8 film on video, colour/sound, 17 min.

Deimantas Narkevicius: Energy Lithuania, 2000. Super 8 film on video, colour/sound, 17 min.

Deimantas Narkevicius: Energy Lithuania, 2000. Super 8 film on video, colour/sound, 17 min.

Deimantas Narkevicius: Feast Calamity. Lithuania at 49th Venice Biennal 2001

'' Europa 54°54'-25°19' '', 1997. 16 mm film, 9 min. Courtesy Galleria Continua S.Gimignano

Deimantas Narkevicius: Too long on the plinth, 1994, shoes, salt, plinth (90 x 40 x 40 cm)

|

|

|

HUO: I hope that we shall be able to arrange an interview which will evolve as a complex dynamic system so that hopefully other people can be invited to ask you questions. But my first question is about your beginnings - where did your work start and how did you become an artist?

DN: I became an artist very early on, and this was because of my parents. We were living in a forest in South Lithuania and they wanted me to move to the city. I went to school in Vilnius and so was separated from my parents - that was when I was fourteen. It was an art boarding school. It was intended for so-called 'talented' people, so I grew up there. I was doing life drawings, modelling and so on. Much later I studied at the art academy and there was always the feeling that something was not quite working. That was even before the '90s, still in the Soviet Union. There was something impersonal in the practice of artists. Everything was quite impersonal. At the beginning I was trying to personalise what I was doing, to motivate myself.

HUO: And that was in the '80s?

DN: That was in the early '90s.

HUO: I started to know your work through Manifesta II, through your filmic work, so I wondered if you could tell me about the origins of your work with film and the context in which this work was born? We have previously spoken about Jonas Mekas and so I was wondering if he was an inspiration for you, or whether there were other filmmakers who inspired you?

DN: I graduated from the art academy as a sculptor. I was not concerned about what was going on in the art academy in Vilnius. I had a chance to go to London for just one year, between 1992 and 1993, which was really great. Coming back I was very much interested in site-specific objects, the places where objects are placed. But somehow it was not enough. I really needed things to tell. So I started to do interviews.

HUO: Recordings of interviews with people in the street?

DN: Just recordings of conversations. Then I found it a really perfect medium for narrative, for exploring sound as well as visual language. For a long time, Jonas Mekas and George Maciunas.

HUO: ...Who is also from Lithuania...

DN: Yes, the works of those artists didn't have a substantial impact on the art scene in Lithuania. Also the relationship to film was very local. So everybody knew their names, but there always was a certain alienation from what they did. In the mid- '90s, perhaps in '96, a big show of Fluxus from the United States and Germany was held at the CAC, which changed this relationship.

HUO: A book has just come out: Flux Friends, edited by Jonas Mekas. It is essentially a conversation between Jonas Mekas, George Maciunas, Yoko Ono and John Lennon. It's very hard to edit the interview, so it leads to a montage. It is almost a new medium, a new literary category, which is the montage book - not unlike the montage film. It prefers to avoid the linear in favour of an informed assemblage of archives, interviews, texts, extracts from newspapers and so on, using all styles from the cinema - flashbacks, ellipse, sequence, the insert and so on. You mentioned that your filmic works start with interviews, so there are perhaps some similarities with Jonas Mekas. Maybe to come back to Mekas and Maciunas - you said that for you they weren't just artists?

DN: They are more than just artists for me, not only because of their connections to the place that I am from. With Jonas' films, it's not that I just put a tape in a VHS player and watch it. There are other things too. It's almost too difficult to describe. Just seeing it on a monitor already means a lot for me. Mekas and Maciunas were very important, and they led me to thinking about the nature of an artist - what is an artist? These artists meant for me more than any teacher I had at that time. At the end of the '80s, Utopia was something impossible. So that's my relation to those people.

HUO: And were there other filmmakers that were important for you? Since the beginning your films have been about different narrative structures. I wondered if certain figures had influenced you, or whether it was something that came less from cinema and more from your work with sculpture and painting? You keep these links to other mediums in your work - years ago I saw your concrete football sculpture in Zagreb. [DN laughs] You continue to do installations and sculptural work, though your most recent work is influenced by film. There are several questions in there - maybe you can untangle them!

DN: Well, actually, in response to the first part of your question about film influences, I would say that I wasn't really influenced as such, but something that was significant for me was the documentary material on the 16mm film that we used to have on TV in the '70s. Interviews used to be filmed with 16mm cameras, and then they were processed and made ready for the evening news on the same day. So it was often done in quite a rush. This rush provoked considerable experimentation. These films were screened and then broadcast, raising interesting possibilities for using film. I didn't think about this until much later, but I realise now that it was really important.

HUO: And was this specific to Lithuanian television?

DN: No, I think it was true of the whole of the Soviet Union. That was during the '60s and '70s, and this indirectly influenced my awareness of the way that visual information was conveyed.

HUO: So this was before television became a more homogenised medium?

DN: Probably, yes. In terms of filmmakers, well, I don't know. I was talking to Jeff a few days ago and we were asking about each other's favourite films. I posed the question: 'what is the earliest film that you remember?' For me, that was probably the second part of Ivan Grozny by Eisenstein, especially the end. I remember that I was five years old when I saw it, and it was really shocking for me. A few years later, I saw his Bronenosec Potiomkin. These were very early things I remembered.

HUO: And what was it that struck you about Eisenstein?

DN: I couldn't really say. If you remember the end of the second part of Ivan Grozny, it's a kind of weird wild dancing, and other suggestive performances. This strangeness, moving out of everyday normality, and in particular, moving out of history gave a sense that there are many possibilities for transformation.

HUO: In terms of the post-medium condition, Rosalind Krauss describes the idea that artists have different media and so with Ed Ruscha, the medium he uses is not necessarily painting, but rather the car. Or with Dan Graham, it's not sculpture or installation, but rather it's architecture. So I was wondering what you would say your medium is, and if you could tell me more about the interesting remark you made yesterday when you said that your previous film was more about painting and that your new film is more about sculpture?

DN: Well, I think my film is sort of an extension of my sculpture. For Manifesta II, I made an installation using films. These films dealt with space. The projectors were equally important. In terms of painting and sculpture, Energy Lithuania, which I made two years ago, is an ongoing image like a painting. Even the Super8 colours are not documentation, they don't have much relation with actual colours. It's difficult to transform a visual language into a spoken narrative! When I was making the film I was thinking of it as a documentary, but the connections with painting very much emerged during the editing process. It seemed that the editing had much in common with many qualities of painting. The documentary element of the film became more distanced. Painting itself cannot really be a documentary - this was a subjective documentary that has a relationship with painting. I brought painterly subjectivity into the documentary, meaning that really it was no longer a documentary. With a new film, I'm trying hard to engage myself in certain situations where I do not know what to do. I'm trying to put myself into totally new situations in which I have no experience of how to solve certain problems.

HUO: So you don't have a completely pre-written storyboard? Does it somehow evolve through the unpredictable? How far do you plan a film, and how far do chance, randomness and the unexpected enter the process of making a film?

DN: It's probably like making a sculpture, though not in the sense of modelling objects. Rather it is a matter of choosing an area in which you're going to work. It's more like a sculpture for a specific location. Within this area that you yourself define, I start to look for a certain structure. Because of the specificity of medium, there are always things that I leave to happen in unexpected ways within the filmed objects and people, the unexpected surfaces. I'm always clear about what I'm doing, but I always leave a space for things to happen that aren't necessarily expected.

HUO: Could you tell us about how this works in the new film that you presented yesterday? You have moments of acceleration and slowness, and even animation.

DN: As with my other films, the main protagonists don't really appear in the film. They exist through narration and through the objects in the film. Again, this is about the idea of subjective documentary. I asked the main character's brother to make his brother's animated portrait, which appears in the film, and this is the kind of way in which I try to involve people so that their relationship with the film is special and not neutral. It is a portrait of the main character who talks in the film but appears through the drawing as an animation. That's an important aspect of documenting things - I don't always film a portrait or a talking head, but things that are related to the person in different and more diverse ways.

HUO: Another question relating to your new film concerns Utopia and Dystopia. In our last conversation you said that you felt this new work was related to these themes. Could you tell me a little about this?

DN: Well, the narrative is about being creative or creating something. It is also about the impossibility of creativity, when creativity reaches a point where it is not fulfilling. Even if you feel that you have given everything, like the character that I just spoke about did, creativity is Utopia in a particular situation and it always reaches certain limits. It is this pushing of the self to these limits that is something that I find intriguing but cannot control. Utopia is about understanding what being creative is, and the failure of that. It's difficult to say in a few words. Being creative with a definite target is Utopia.

HUO: Ernst Bloch once said that 'something is missing'.

DN: Yes, probably, something is missing: communication not by talking about something, but in relation to something. Utopia is doing something yourself and creating yourself, coming to certain limits in a particular situation. In my film, that is the situation and that is a Utopia. The second part is about relations - personal and other.

HUO: So it's an idea that is concerned with defining a new social contract. After '89 'Utopia' as an idea became very unpopular. You lived a very specific experience in relation to the moment of '89, so at that time there was also an anti-Utopia moment. But if we revisit Utopia today, the advantages of Utopia are that it still offers possibilities for defining a social contract not in a totalitarian way but very much on a more human scale.

DN: My context is a country that was built on a social and political Utopia. But I grew up in the period when nobody really believed in it. The fall of the Soviet Union was at a time when people had other Utopias. These were liberal Utopias, about freedom to do what you do. These kinds of Utopia were also an illusion, and lasted only for a few years. People grew disillusioned very quickly. What kind of Utopias can be created on a human scale? That is the question and I don't have an answer.

HUO: Do you have any unrealised projects? Are there projects that have been too big or too small to be realised? Projects that have been censored, projects that have been too cheap or too costly to realise, projects which you had forgotten about? What are your unbuilt roads?

DN: Until now, when I started working on each of these films, I didn't know if I ever realise them. I didn't know the costs of working in this medium. I didn't know how much time it would take to realise my projects. I've never had any big plans that would be beyond my control, projects that I can't do by myself or with the help of my friends. So I don't know if I have any unrealised projects. Maybe there are some ideas that I will pursue one day, but I didn't and I still don't know when and how to do that.

HUO: That's a very anti-monumental approach to art, leading us to the insert in the local paper yesterday, which is a newspaper sculpture about there no longer being a need for monuments. Could you tell me a little more about this?

DN: Well, it's part of the text from the film. The character in the film gives a long monologue in which he talks of the importance of a monument, and then he says that there is no need for a monument itself. The process, how it is done, the story behind it and its circumstances are of importance: everything around the monument is of significance, except the monument itself. And that's interesting in relation to film in general. It's not documenting the story or filming the story you have, it's documenting the process of how you deal with it. That is the monument, not the object itself.

HUO: In relation to what is not there, you told me a fabulous story yesterday and we need it on film here today. It was the story about Herzog - something was missing!

DN: That's probably the answer to your earlier question about filmmakers who have been important for me. To be honest, though, I saw Werner Herzog's films quite late. I had already started working on my short films. But I was really amazed by his personality when I had a chance to meet him. I don't know how many films he has made, but it could well be over fifty. It was just a small remark about a kiss that first appeared in his latest film. When you filmed half a hundred films and a lot of them are about male/female relations, and when you are more than sixty years old, that gives something very special in terms of understanding time. Even a film itself has a temporal quality. But the director as an artist was above it, which is really great when considered alongside the interrelationships of everything that you do. And that is true not only of Herzog but of Abbas Kiarostami, when characters from one film appear in another, and stories cross over too. That's a very important form of understanding that works against monumentality. Things appear and disappear in time: giving the idea of duration, even of a very long film, is very important. It leads to an understanding of the existence of parallel times. Film is an illusion of a certain time. In the space of two hours you can see a saga that spans several years. Yes, an understanding of parallel timescales within the medium is important for my work.

HUO: That also leads to the question of slowness - we had a discussion in San Gimignano with you, Pistoletto and Chris Derkon on slowness. Slowness seems to be becoming very sexy at the moment, very fashionable. Architects and all kinds of practitioners are preoccupied with slowness at the moment. With artists I get the impression that there is more an emphasis on duration than on slowness. We are obviously at a moment of the homogenising forces of globalisation, though not only in terms of space but also in terms of time. There seems to be a certain resistance among artists to that - Pistoletto said he has a ten-year project, resisting some of the temporal constraints often placed upon artists. I was wondering if you could talk a little about these issues of temporality, duration and slowness?

DN: Either in New York or in Vilnius, if you say that someone is slow, you are saying that he is kind of stupid! [laughs] It's very important for any artist not to be frightened by duration. There are going to be different paces during different phases of your life, and it is this that leads to a sense of understanding of your motivation and the work that you are making. It is important for artists.

HUO: It's a resistance to fragmentation.

DN: It strikes me as something significant.

HUO: And does longer duration mean that they are going to be larger projects?

DN: No, it's just a continuation of different projects. I don't have any long term projects myself, but any fragment has to be naturally motivated, and this is probably a form of resistance to fragmentation.

HUO: A question I wanted to ask, and perhaps we can start with this question next time we meet, is about memory. Memory plays a large role in all your films, not just in the 'energy' piece and most recent pieces, but also in your earlier works. Memory is dynamic and not nostalgic in your work. It is not about a nostalgia for Lithuania before 1989, but a more dynamic form of memory.

DN: [laughs] Memory is a funny thing. I think our brain has a filter: You remember what you want to remember. And you recreate the stories of the memory in a way that you want to remember them and how you would like to create them. It's a natural filter. I'm very conscious of this natural filter. One of the first films I made was about the filter processes of the film medium and my own stories. These were tragic in a way. Everything that I did in the film His-story, was using film and projectors as if from an archive of the '70s. The films were even processed in a lab using the original processes. It's a little like an archaeological exploration of that time. It's my parents' story, based on the memories that you think it is good to tell. But both the medium itself and the story, and the way that it was told, seems nearly melancholic, and a certain tragedy can be sensed behind it.

HUO: You mentioned yesterday that in Jonas Mekas' films, the happiness is also not happiness.

DN: Yes, like in my film Legend Coming True: Fania from the Vilnius ghetto is talking for a long time about a very dramatic period, but there is no real horror in what she is saying. You can feel that there are many things that run parallel to that...

HUO: Thank you very much, I look forward to hearing more about this next time we speak.

|