Jane Alexander

dal 24/3/2011 al 20/8/2011

Segnalato da

24/3/2011

Jane Alexander

La Centrale for contemporary art, Bruxelles

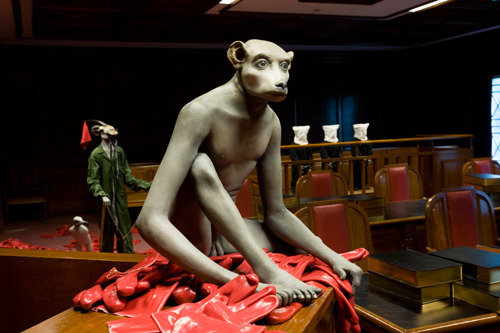

Security. The combination of individual figures, tableaux, installations and photographic work from the last decade presented in this exhibition offers viewers an opportunity for exposure to the variety of Alexander's surveying strategies and to the ample scope of her artistic universe. From its inception in the early 1980s, while South Africa was still under the rule of the apartheid regime, Alexander's artistic practice has been deeply sensitive to socio-political issues.

Surveys from the Cape of Good Hope

Jane Alexander was born in Johannesburg, South Africa, in 1959, and currently lives and works in Cape Town where she also teaches at the Michaelis School of Fine Art, University of Cape Town.

From its inception in the early 1980s, while South Africa was still under the rule of the apartheid regime, Alexander’s artistic practice has been deeply sensitive to socio-political issues as a part of her interest and observation of human and other animal behaviour in and beyond her own social environment. That is, her concerns do not refer so much to issues, ambitions, and conflicts around conventional political power as to the all-too-frequent drift of all varieties of power relations that consolidate into permanent structures and regular routines of authority and control, often instrumental in oppression and abuse.

In Alexander’s approach social conditions and phenomena, even when taking place at a global scale, and individual processes, even when strictly subjective, are not considered and elaborated as independent from each other but investigated and expressed as two tightly interdependent, inseparable realities or, better, as a single reality with two facets.

In other words, her artworks explore simultaneously both the social and the individual phenomenology of human existence and behaviour, as well as its “rational” and its not so “rational” components.

In this regard, her “humanimals” –to borrow Julie McGee’s fitting neologism –, embody and may prompt us to consider the porous borders between humans and other forms of animal life.

To this extent, all of Alexander’s work deals with our inherent hybridity and mutability, with the multiple “others” that inhabit us behind the conventional characters that we successively impersonate in our everyday life.

The result is a multifaceted and open-ended body of work that defies categorization, different artworks by the artist highlighting different dimensions among the multiple and often conflicting motivations and relations that converge in human behaviour and social life.

Having created the most powerful artistic expressions of the evils of apartheid –most notably her Butcher Boys (1985-86) during a State of Emergency–, at the turn of the millennium, when South Africa was reinventing itself as a multicultural, equal-rights democracy, Alexander shifted her focus to the translation (or lack of it) into everyday conditions of life of the deep political changes the country was going through. At the same time, she extended her field of references to situations and processes that, even if still grounded in local realities and observations, clearly overflow national frontiers. The resilience of racial-based prejudices and forms of discrimination; the reproduction of neocolonial forms of domination; the ever growing obsession for security and the parallel global proliferation of fortified borders and systems of surveillance, are some of the dominant themes of Alexander’s recent work.

As in the apartheid period though, Alexander’s approach to these problematic phenomena has continued to be akin to that of a nonjudgmental surveyor mapping the forces, interests, passions and effects at play in human relations and exchanges. In so doing, her artworks transcend their locality to show everyday existence being torn everywhere between the rhetorical constructs that argue for a peaceful and decorous life, and the unruly human capacity for conflict and violence.

In her search, however, the artist doesn’t indulge a morbid fascination for the dark side of being human, but recognizes our enormous potential for resilience, agency, and dignity in the face of adversity and deprivation as well as the fear and vulnerability of individuals in positions of power and command.

The combination of individual figures, tableaux, installations and photographic work from the last decade presented in this exhibition offers viewers a rare opportunity for exposure to the variety of Alexander’s surveying strategies and to the ample scope of her artistic universe.

Pep Subirós

Curator

EXCERPTS FROM “NOTES ON AFRICAN ADVENTURE AND OTHER DETAILS”,

BY JANE ALEXANDER

ON RESEARCH AND INTERPRETATION

All my figures, male/female, hybrid or doll-specific, are intended to act, with a degree of realism, jane2representation, and invention, as an imaginative distillation and interpretation of research, observation, experience, and hearsay regarding aspects of social systems that impact the control and regulation of groups and individuals, of human and nonhuman animals. The viewer is entitled to and does project her or his own interpretation onto the work without explicatory mediation from me other than via a series of recognized or unrecognized keys embedded in or surrounding the presentation of the figure: the title and accompanying caption, sometimes the site, and the elements included in the installation or tableau.

Insofar as it has been possible, I have chosen not to explicate my work for a number of reasons. One is that my preferred language of expression, and the one I believe I am more articulate in, is visual; another is that whatever one hopes to be understood or that one intellectualizes regarding one’s “intentions” in artwork does not necessarily and often doesn’t correlate with what is perceived by the viewer outside of the text. It is also arguable to what extent the artist can in fact identify a degree of significant “accurate” meaning in a way that constructively elaborates on the visual presence without limiting it to the textual explication. And like the viewer, the artist could project a preferred or ennobling interpretation onto the work. If I were able to articulate my intentions effectively in text I would sooner write, given the immediacy, comparative compactness, and accessibility of words. (November 2009)

AFRICAN ADVENTURE

The tableau African Adventure was conceived (and) evolved largely as a response to my observations and experience of Long Street in Cape Town. During the ten years that I lived there, coinciding with developments mentioned above, it shifted from the closed South African scenario of old-time hotels and bars, Group Areas transgressions, children living on the street, and Victorian architecture housing warrens of illicit underground drug and sex dealers (their consumers and workers, street gangsters and small enterprises having been established for decades) to a gentrified concentration of tourist centres, backpacking residences and recreational clubs mixed with the “protection,” the drug and newly legal sex trades, illegal immigrants and refugees from across the continent.

African Adventure arose from the confluence of my observations of the apartheid experience, my research and attempts to understand the colonial and missionary projects, liberation, and neocolonialism and how they are reflected and experienced in South Africa in relation to the continent and Europe. This was with particular reference to the peculiarities of Long Street mentioned above and the tourist adventure centres there, along with my increasing exposure to migrants and refugees, as well as to the international art world and African diaspora. The work continues my endeavor to comprehend social issues related to Africa and the associated discrimination that certain groups of people experience everywhere. (March 2010)

ON SECURITY AND LIVING GUARDS

jane3Security is a constant concern in South African experience, expressed in the high level of control surrounding access to domestic and public spaces, the alarms, surveillance cameras, razor-wire perimeters, private security guards, panic buttons, vast numbers of licensed and unlicensed formal and informal weapons—a response to pervasive, sometimes very ruthless violence.

So present as to be almost invisible, South African security guards, official and unofficial, often untrained but experienced, are extremely vulnerable, sometimes informally armed, almost always poorly compensated, mostly “black” men in uniforms with batons who work long empty hours to protect us. They are hired and chosen over and above the often inaccessible police, through armed-response companies that some of us link our lives to through costly contracts and “panic buttons.”

Security guards are the only actual people who are encountered in my work aside from in images and video. In some instances they are the very guards some of us rely upon, and are present in this capacity as themselves, as in Security, exhibited in Johannesburg in 2009. In other presentations of Security, in Brazil and Sweden, these men were included with reference to forced and voluntary migration and the social and economic conditions associated with it. …

I have been criticized for “objectifying” people and “using” immigrants and Africans in my work, as have many “white” South African artists who represent the “black” body and/or experience one way or another, through either imaging or presentation of the actual body, living conditions and spaces, and/or associated details. The ethical /racial / psychological problematics raised by these contentions are various and complex: I am not arguing them here, but I note that they are not exclusive to South Africa or the “black” body, and they remain a notable and curious extension of the complexities of this particular racialized heritage. (June 2010)

USES OF AFRICA

I have an interest in how Africa has been consumed as a resource in art, for example with jane4reference both to commodification, historically and currently, and to institutional representations of Africa in South Africa and particularly in Europe and North America. I am also interested in the position that aspects of modern and contemporary European and North American art—including conceptual, performance, land, and installation art—arguably have a precedent in historical art practice in Africa. …

Also important to me is consideration of how art forms have been introduced to and sustained from outside the continent, the way in which exposure to art and creativity has been controlled or directed, and the impact of this influence on art and craft produced by people in Africa. Olu Oguibe describes this historically, with reference to the missionary project, as the “perfect conditions for the manufacture of utilitarian craftsmen who had no confidence in the worth of their own art traditions and no access to imperial Enlightenment either.”

This continues to impact on current conditions. There is clearly still the predilection for the exotic and the marketability of otherness that have always characterized the circulation and consumption of art from Africa, but there are also positive opportunities for South African artists to create freely, to exhibit work internationally, and to sell competitively which are relatively recent. Access to art education, however, is still extremely limited in most schools, often economically inaccessible, mainly devised and often taught by “white” professionals at a tertiary level, often based on curricula founded on “imperial Enlightenment,” to use Oguibe’s phrase, and subjected to academic and linguistic forms and environmental conditions that disadvantage candidates who speak English as a second language and who have not had access to an education qualitatively equivalent to that of the privileged minority. This is particularly so for speakers of African languages who form the vast majority of the country’s population although Afrikaans speakers are affected as well. (March 2010)

ON VIEWERS’ RESPONSES

jane5My work is intended to be experienced viscerally as well as intellectually, and as mentioned, it provides various kinds of conceptual markers (to be considered or not): evocative, environmentally descriptive, and specifically referential. It is my hope that my work, the content and articulation of which virtually always has aspects of realism, can convey meaning to anyone, not just an informed elite, and that I could hone it enough to contain interpretation, at least to the extent that it is important. At the same time “(mis)interpretation” has value as well. Many references are embedded in the work that can be identified, interpreted either by association or through more complex inquiry, for example through keys such as the relevance of the site or components like machetes, sickles, industrial-strength gloves, flags, specific ammunition boxes, clothing, or less obvious indicators which are identified in the captions and/or recognizable. In the end what I intended, or thought I could convey if indeed I knew, is not important. The work is a response to a series of experiences, observations, theories, and interpretations of the visual, political, geographic, and primarily social environments that have prompted me to produce the artwork. There is no fixed meaning. (November 2009)

In collaboration with Art Brussels

Hamza Fassi-Firhi

Alderman in charge of Civil Status, Cultural Affairs and Employment-Formation

cabinet.h.fassi-firhi@brucity.be

Communication and Public Relations

Jenyfer Garcia-Gonzalez T + 32 (0)2 2796445 Jennifer.garciagonzalez@brucity.be

La Centrale Electrique - European Center for Contemporary Art

Place Sainte-Catherine 44 - 1000 Brussels

Open from Wednesday till Sunday 10.30 am > 6.00 pm

Closed on Public Holidays

Tickets : 6 € / 4,50 € / 2,50 €