The Translator's Voice

dal 28/1/2015 al 2/5/2015

Segnalato da

Sylvie Boisseau

Frank Westermeyer

Erik Bunger

Luis Camnitzer

Rainer Ganahl

Dora García

Joseph Grigely

Susan Hiller

Christoph Keller

Fabrice Samyn

Zineb Sedira

Mladen Stilinovic

Nicoline van Harskamp

Ingrid Wildi Merino

Martin Waldmeier

28/1/2015

The Translator's Voice

Frac Lorraine 49 Nord 6 Est, Metz

A group of artists to reflect on the question of translation in the global present. Languages and cultures are not different ways of saying the same thing, but different ways of saying different things.

Curated by Martin Waldmeier

“In the beginning there was … translation,” the Finnish poet and translator, Leevi Lehto, wrote. Translation is the true basis of culture, he argued, and “traffic” between cultures and languages is what lets them grow and change over time. Translation lets the foreign enter our world; it lets the foreign speak to us in a language that we can understand, and, in the process, it expands and changes our point of view.

With “The Translator’s Voice,” we invite you to join us and a group of artists from around the world to reflect on the question of translation in the global present. Today, translations are everywhere: facilitating international trade of goods, enabling diplomatic negotiations between political leaders, interpreting our daily news broadcast, permitting online communication between countries and continents, and introducing us to foreign films and literature. Much of what we know about the world has reached us through translation: as the pace and intensity of global communication and circulation are accelerating, the need for translations is growing.

It’s not only since the popular film “Lost in Translation” that the process of translation has also been associated with loss. Languages and cultures are not different ways of saying the same thing, but different ways of saying different things. Translation is therefore always an approximation, an infinitely difficult task of mediating between different expressions of human experience. How can we, then, think of encounters between languages not only as a challenge and a difficulty, but as a source of creativity and learning? How can we understand the world differently in different languages? Can translation be a place for critical or even subversive activity?

Translation is of course not a new phenomenon, despite globalization. Every encounter between cultures has always required translation, and throughout much of modern history, these encounters have been neither equal nor peaceful. While English is increasingly perceived as a hegemonic language, criticized as displacing minor and vernacular languages, its power is preceded by centuries of colonialism(s) and imperialism(s) that have imposed similarly hegemonic languages upon colonized peoples, systematically using their languages to suppress native cultures.

If one is to claim that “in the beginning there was translation,” then one must also acknowledge that, from the very beginning, translation has always been defined by the historic relations of power between the colonizers and the colonized, between centers and peripheries, between minor cultures and empires, and some of those relations continue to persist today, albeit in new forms.

The title of this project, “The Translator’s Voice,” points in two thematic directions. On the one hand, it encapsulates the idea of making visible the activity – and the voice – of translation, and the gesture of letting it take the center stage as a unique source of knowledge about the nature of cultural differences and about different ways of expressing identity through language.

On the other hand, the figure of translator becomes a critical metaphor for the linguistic conditions of globalization and the postcolonial era: the growing need for – and the joy, and the pain of – learning foreign languages; the intentional and unintentional multilingualism of migrants, and the phenomenon of hybrid cultures and “accented” ways of speaking and experiencing the world.

Here, translation no longer designates just a profession, or an activity. It represents human condition, and more and more often, we find ourselves assuming the role of a translator…

Martin Waldmeier

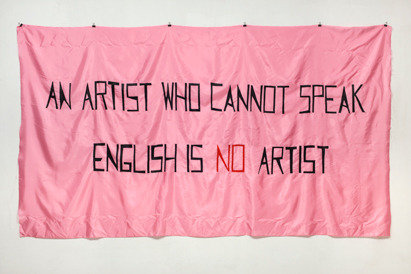

Image: Madlen Stilinovic, Artist Who Cannot Speak English Is No Artist, 1992. Drapeau. Courtesy de l’artiste, Zagreb. © L’artiste, photo: Boris Cvjetanovic

Press Contact:

Valérie Audren-Guelton, communication@fraclorraine.org

Opening: Thursday January 29, 7pm

49 Nord 6 Est – Frac Lorraine

1bis rue des Trinitaires

F-57000 Metz

France