John McCracken - Paul McCarthy

dal 21/1/2005 al 19/3/2005

Segnalato da

21/1/2005

John McCracken - Paul McCarthy

Hauser & Wirth, Zurich

John McCracken's objects are marked by a reduction to simplest geometrical shapes and surfaces in bright, monochrome colour. Works on display include five monumental columns in various monochrome colours and smaller wall pieces and planks. Paul McCarthy has gained a reputation as a sharp analyst of US society at its most media-crazed and consumption-oriented. In the show are included: painted sculptures

The works of West Coast artists John McCracken (b. 1934 in Berkeley) and Paul McCarthy (b. 1945 in Salt Lake City) have never been engaged in direct, exclusive dialogue in any single exhibition. At first sight, then, this juxtaposition of the two oeuvres certainly comes as a surprise. John McCracken and Paul McCarthy are among the most widely influential and most important artists of their generation. Their works are included in numerous international collections and are exhibited in renowned museums and institutions.

Following solo exhibitions at the Tate Modern in London in 2003 and at the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven in 2004, Paul McCarthy has comprehensive shows planned for 2005 at the Haus der Kunst in Munich and for 2006 at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm in 2006. John McCracken’s work was shown in a large-scale solo exhibition last year at the S.M.A.K. in Ghent.

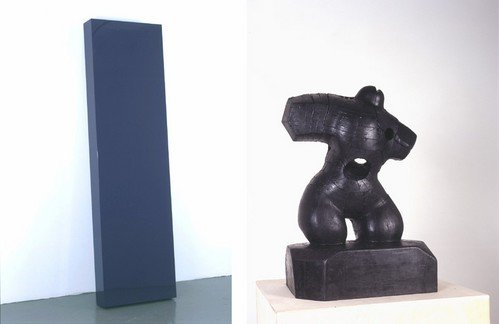

John McCracken’s objects are marked by a reduction to simplest geometrical shapes and surfaces in bright, monochrome colour. With his large, reflecting sculptures, he belongs to the group of sculptors who, in mid-60s California, set about developing a somewhat more playful version of Minimal Art inspired by the local car culture. Works by John McCracken on display in the current exhibition include five monumental columns in various monochrome colours. They are accompanied by smaller wall pieces and planks.

Paul McCarthy has gained a reputation as a sharp analyst of US society at its most media-crazed and consumption-oriented. Making use of a formal vocabulary that is clearly out to provoke, and a working method that draws heavily on subconscious processes, he develops apocalyptic scenarios to examine the effects of those phenomena on collective and individual patterns of behaviour. And prominent among the figures that enable him to get at the soft spots of the collective subconscious is Santa Claus.

In the show are included: two bronze, painted ‘Santa Candy Cane’ sculptures, one ‘Santa Candy Cane’ made of green carbon fibre, one ‘Santa Long Neck’ in painted bronze, one in red, monochrome carbon fibre and a ‘Santa (with Butt Plug)’ in brown carbon fibre. A small ‘Henry Moore’ sculpture rounds out the group of works by Paul McCarthy on display.

McCarthy creates his sculptures in series of variations: in various materials (bronze, silicon, carbon fibre, inflatable); in various colours, both monochrome and multi-coloured, and with various surface treatments (polished or patinated bronze, in monochrome coloured synthetic material, or hand-painted); and in various experimental dimensions. Thus, for example, he presented a large-scale version of the small black ‘Henry Moore’ carbon-fibre sculpture at the 2004 Whitney Biennial: an oversized, inflatable outdoor work, it was installed on the rooftop of the Whitney Museum, the central idea being that the Museum building would be turned into a pedestal for the blow-up sculpture.

It is as if by continually re-interpreting the same motifs, and by realising them in an almost ecstatic multitude of possible combinations of material, colour, size and treatment, Paul McCarthy attempts to capture that which is not perceived by our modest senses, that which lies beyond appearances – the sublime.

In his performance ‘Tokyo Santa’ and the subsequent video installations, drawings and photographs, Paul McCarthy also used the Santa Claus motif to explicitly examine the concepts of painting and sculpture and their relationship to movement and space.

The bronze sculptures in the present show were painted by Paul McCarthy himself in a manner inspired by Action Painting. He covered the bronze surface with an additional skin that now envelops the whole sculpture, condensing his artistic intuition and mood into an abstract, expressive chance painting. In an instance of Paul McCarthy’s ‘inside out’ principle, i.e. the relative change in perspective, the painted ‘Santa Claus Candy’ can also be read from the point of view of the object: McCarthy deconstructs the sculpture both in terms of form and content, always with the aim to get at the true nature of things. He translates this idea into three dimensions. Using the instruments with which he created the sculpture, he penetrates it, destroying its protective skin: what is inside is made public, flowing to the outside.

Paul McCarthy deliberately combines figurative and abstract minimal elements. Thus, Santa Claus’ bag is filled with long, thin sticks as well as candy canes, and the figure is standing on a rectangular slab.

If we now turn to the serene, monochrome, geometrical works of John McCracken, what immediately strikes us is the way in which he keeps questioning their basic matrix by using a few, recurring shapes, and the obvious pleasure he takes in rich, pure colour and in the sheer materiality of paint. And the works of both artists refuse to reveal their methods of production the viewer’s gaze: contrary to what might be expected from their purist look, McCracken’s objects are not produced industrially, as the wider context of Minimal Art might suggest. Each is painstakingly hand-made by McCracken himself, who carefully paints them, layer upon layer, in an almost romantic manner. Paul McCarthy, on the other hand, makes extensive use of existing possibilities of high-tech production. But to both artists, painting is also sculpture, and vice versa.

Unlike McCarthy, who follows the unnameable into the depths of the human soul, McCracken turns his gaze upwards to the New Mexican sky. He likes to call his objects ‘energy objects’ or ‘thought objects’. Like a semi-permeable membrane, these mythical shapes communicate between the real world and the sublime. The spiritual sensibility of the objects and McCracken’s use of pure geometrical form and colour are clearly abstract and expressive qualities, related to the work of Suprematist artists around Malevich, but also to Mondrian and Kandinsky.

While McCracken has progressively moved away from the context of Minimal Art, Paul McCarthy’s work has recently been shown to have hitherto unnoticed links with Minimalism that are like a thread running through his entire oeuvre. The Minimalist ideas and forms, with their three-dimensional qualities, define relationships, delimiting an abstract inside and outside, an above and below. Paul McCarthy also uses them to make the human figure more abstract. In Eva Meyer-Hermann’s words, the spaces and Minimalist shapes are to be read as ‘empty containers ... to better stimulate perception.’ Meyer-Hermann, Eva (ed.), Van Abbemuseum Eindhoven, ‘Paul McCarthy. Brain Box Dream Box’, Düsseldorf: Richter Verlag, 2004, p. 10

And interestingly enough, they also open up a space for a spiritual level, turning into vehicles for intangible, transcendental elements. Thus, a 1968 concept for a performance titled ‘A bottle full of burnt paintings’ reads: ‘.spirit intangible – shell screen/ skull./ destruction is shit maybe/ open at both end boxes on/ sides covered. To hold intuitive/ space (spirit) – water passes/ through gas passes through’. (in: Meyer-Hermann, Eva (ed.), Van Abbemuseum Eindhoven, ‘Paul McCarthy. Brain Box Dream Box’, Düsseldorf: Richter Verlag, 2004, p. 35)

The example takes us back full circle to John McCracken’s geometrical objects as they embody the reduction of an idea to its essential form.

I.

In a 1998 interview, critic Frances Colpitt asks John McCracken about the spiritual aspects of his work, especially his ongoing interest in the existence of extraterrestrial life. Asked whether he had noted the resemblance of his objects to the monolith in Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 film, ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’, McCracken feels he is being understood: ‘That’s a good example of what I’m talking about. Of course, that monolith was essentially a technological instrument – but I sometimes think of my works as technological instruments, too. At the time, some people thought I had designed the monolith, or that it had been derived from my work.’ Was he surprised when he saw the monolith in the movie? ‘Somewhat, but I think it’s an example of how multiple expressions of the same idea can happen more or less simultaneously and be appropriate for the times.’

Art in America, Between Two Worlds, John McCracken interviewed by Frances Colpitt, 1998, p. 89

II.

A bottle of soy sauce has left blurred stain circles on a paper table mat, some stray grains of rice lying around them in no particular pattern have gone cold during dinner. After the plates have been removed, the curator discovers several small, meticulous pencil drawings of figures and shapes, accompanied by numbers and words: ‘Intangible Contained, Minimal, Stoned Blue, Brain Box, Pirate Project’ etc. Then she notices the detailed sketch of a shiny Minimalist object: a small cubic column. ‘What’s this?’ she asks Paul McCarthy, who had been doodling away throughout dinner. ‘Remember the monolith in Stanley Kubrick’s “2001: A Space Odyssey� Isn’t it funny the way it drops out of space on a prehistoric Earth? ...’

Meyer-Hermann, Eva (ed.), Van Abbemuseum Eindhoven, ‘Paul McCarthy. Brain Box Dream Box’, Düsseldorf: Richter Verlag, 2004, p. 12

Opening: 21 January 2005, 6 pm

Galerie Hauser & Wirth

Limmatstrasse 270 CH-8005 Zurich

Gallery hours: Tue–Wed 12 noon–6 pm, Thu 12 noon–8 pm, Fri 12 noon–6 pm, Sat 11 am–4 pm