L'edicola digitale delle riviste italiane di arte e cultura contemporanea

Kaleidoscope Anno 2 Numero 6 aprile-maggio 2010

Roberto Cuoghi. The Rules of Vision

Marcella Beccaria

Anamorphosis in the Eyes

a contemporary magazine

-THE ITALIAN ISSUE

(April – May)

New Issue Featuring:

ART: Marcello Maloberti by Sabine Folie; FUTURA: Patrizio Di Massimo by Hans Ulrich Obrist;

SPECIAL PROJECT 01: Jan De Cock;

ON EXHIBITIONS: Germano Celant by Paola Nicolin;

ENIGMA No.6 by Meris Angioletti;

ART: Gianfranco Baruchello introduction by Eva Fabbris, interview by Maurizio

Cattelan;

EMERGING ARTISTS: Rossella Biscotti by Moosje Goosen, Andrea Sala by Noah Stolz, Giorgio Andreotta Calò by Eva Fabbris, Alex Cecchetti by Chris Sharp, Seb Patane by Caterina Riva;

SPECIAL PROJECT 02: Matthew Brannon;

PIONEERS: Ketty La Rocca by Simone Menegoi;

ART: Massimo Grimaldi by Elena Volpato;

SPECIAL PROJECT 03: Rob Pruitt;

DESIGN: Lili Reynaud-Dewar on Ettore Sottsass by Joanna Fiduccia;

ART: Lara Favaretto by Adam Carr;

SPECIAL PROJECT 04: Francesco Vezzoli & Stefano Tonchi;

LITERATURE: Curzio Malaparte by Ian Kiaer;

MAPPING THE STUDIO: Berti, Previdi, Trevisani, Tuttofuoco by Luca Cerizza;

LAST QUESTION by Enzo Mari.

MAIN THEME: The Italian Anomaly, edited by Luca Cerizza, featuring: An Incomplete Modernity by Luca Cerizza; The Impolitic Community by Marco Scotini; Love Like God by Alessandro Rabottini; My Dark Places by Barbara Casavecchia.

MONO: Roberto Cuoghi. The Rules of Vision by Marcella Beccaria; Six Short Stories by Roberto Cuoghi; The Inverted Life of Roberto Cuoghi by Massimiliano Gioni; Interview by Andrea Viliani.

Torbjørn Rødland

Hanne Mugaas

n. 22 autunno -inverno 2014

John Armleder

Andrea Bellini

n. 21 estate 2014

Voiceover: Under the skin

Shama Khanna

n. 20 inverno 2013-2014

Yang Fudong

Davide Quadrio e Noah Cowan

n. 19 autunno 2013

Massimiliano Gioni

Francesco Manacorda

n. 18 estate 2013

John Currin

Catherine Wood

n. 17 inverno 2012-2013

courtesy the artist

courtesy the artist

courtesy the artist

Cuoghi takes away my eyes and compels me to use his. This is neither a joke nor an equivocal game—rather, it’s what happens every time I encounter one of his creations. His work acquires meaning the instant when my vision changes, when my gaze is replaced by an alien one and other eyes—the artist’s—become mine.

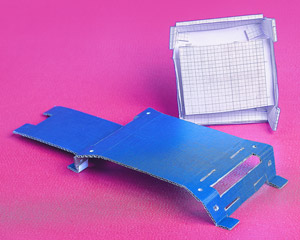

It has an innocent look; there are even children in it. But when I put on the glasses that Cuoghi has given me, my head spins. Kinderama (2010), the artist’s latest project, is based on a series of stereoscopic images. Founded on the principle of binocular vision, which is what allows us to judge distances and proportions correctly, the procedure involves taking two photographs almost simultaneously, but sliding the camera along a fixed ruled bar. The two pictures look very similar to the naked eye, but seen with the aid of a special viewer, the images fuse, creating the illusion of depth. Nothing new about that, some will say, perhaps thinking of those small optical devices capable of conveying the magic of St. Mark’s Square covered with pigeons. And yet, precisely because stereoscopic viewers usually present panoramas of squares and monuments, the entire Kinderama operation takes on significance as soon as you realize that this kind of vision, a sort of low-cost special effect, has been applied instead to a well-known and wealthy private collection. And so it is that, looked at with Cuoghi’s eyes—those eyes that have suddenly become my own—famous works by Jeff Koons, Robert Gober, Maurizio Cattelan and many others become the novel playground of a group of smiling and overexcited children.

A world of fluctuating, amusing, captivating, but also slightly repellent illusion, Kinderama makes you think. While the eyes wander and plumb the depth of the 3D image, the mind responds to the retinal stimulus and starts to see, in its turn, hypothetical metaphors, similes and personifications. Perhaps it is not just a toy… And so what is it? In search of a meaning, you suddenly feel that what you have in your hands is a sort of microscope capable of revealing the secrets of a colony of multiplying bacteria. In that child posing as the Incredible Hulk in front of the picture by Koons, you seem to recognize a familiar scene… perhaps some gallery owner flexing the muscles of his power. And that group of cheerful children dancing in the glare of the light that illuminates Cattelan’s horse? Don’t they remind you of a group of curators clinging to the luminous tail of some shooting star of the art scene? And those poor wretches in the work in the shape of a cage? They’re not by any chance like the people who, wanting desperately to belong to the world of art, end up being imprisoned by it? One image even shows a delightful little girl turning her hands upside down and pretending they are glasses. “A window open onto the world of art” declares a smart art slogan these days… In the end, we like Cuoghi precisely because he sees monsters and puts them everywhere.

I put down Kinderama, take back my eyes and start to think about Cuoghi’s other works. I leaf through his catalogue in my mind. Here they are, in chronological order. First, Cuoghi’s self-portrait Il Coccodeista (1997) (a play on words in which the Italian word for “cackle” takes the place of “cube” or “future”), a confused avant-gardist who lived on pills, spurning showers, combs and changes of clothing. Once again, my eyes are not my own; the self-portraits and sheets of text that make up the series imply a new substitution of the gaze. Cuoghi was a student at the Accademia di Brera in Milan when he had the idea of taking an exam by altering his own already disorderly life. He spent days wearing a pair of welder’s goggles whose lenses had been replaced by Peckham prisms, which have the curious optical property of inverting and reversing the vision, so that whatever is above appears on the bottom and whatever is to the right changes place with the left. All that remains of this experiment is the series called Il Coccodeista. Looking at these works on paper gives a clear idea of the world that the artist saw around him at that time. We don’t need a psychologist to tell us that it was a claustrophobically self-referential dimension, and in fact Cuoghi practically saw nothing but himself (whence the self-portraits). And then there are the texts Cuoghi wrote at the time: genuine anti-poems of intoxicated, cynically fragmented suffering.

The following year was unquestionably the most tormented in the artist’s career. In 1988, he began the process of metamorphosis that led him to transform himself into a middle-aged man, turning his biological age of twenty-five into that of an overweight sixty-year-old. An extreme artistic performance, according to some. A wholly personal matter, in the view of others, Cuoghi among them. Be that as it may, it is certain that the transformation was a way for the artist to lose the years of his own life but gain others in exchange. Thinking about it, what is the act of becoming an older person, his own father to be exact, if not once again appropriating someone else’s eyes? If Cuoghi is able to offer others a glimpse of his own view of the world through his works, in this case it was the artist who imposed the change on himself. By altering his own eyes—and appearance, habits, friendships—Cuoghi underwent a deliberate acceleration and thus paradoxically slowed down a life that was otherwise slipping through his fingers.

Every artist constructs images and, if he or she is really good, invents the laws that define their vision as well. In the history of art, the construction of the vision, of the point of view, of perspective, has always been an intentional act—perspective as “symbolic form,” as Erwin Panofsky writes. Accelerated perspectives, decelerated perspectives, anamorphic distortions… The rational rule of perspective can be adapted to the most fantastic irrationality; through each of these versions of it, artists have expressed and sometimes anticipated the cultural climate of the age in which they lived. Turning two points of view into one, and thereby fusing in the mind references that would otherwise lack depth, is a procedure that also defines The Goodgriefies (2000), a work that takes its inspiration from familiar protagonists of the world of American cartoons. In the video, each of the characters created by Cuoghi is a product of the superimposition of two or more original cartoons. Mutant beings, subjected to a corrupted perspective, the Goodgriefies are a gallery of monsters, a true aberration of the gaze in the etymological sense of the term.

In 2002, Cuoghi began the Black Paintings, a series of works inhabited by human, or humanoid, forms—creatures suspended in intermediate stages of evolution. To see a Black Painting, you have to move about, changing the position of your body and letting your eyes rove a good deal. Then, depending on the angle from which they are observed, the subjects materialize on the surface of the painting or withdraw from it, as if vaporized. Created by superimposing many layers of mixed materials, including enamel, pastel, watercolor, pencil and ink, and combining a variety of chemical reactions, each painting makes clear Cuoghi’s penchant for experimentation. Like an obsessive alchemist tinkering with evil-smelling glues and solvents, Cuoghi classified the results of his own experiments, so that each work is like the sum of the knowledge acquired in relation to particular chemical combinations. It seems as if we are reading about one of Giorgio Vasari’s Lives of the Artists, perhaps that of a true professional of alchemical eccentricities like Parmigianino (even if we are in Milan and not Parma, and the air is filled with the acid rain of late capitalism rather than the mists of mannerism).

Cuoghi continued to apply this experimental method in subsequent works as well: first in the drawings, the Asincroni (Asynchronies) (2002–04), dominated by a truly spooky smile imposed on the features of a deceased relative, and then in the songs, with Mbube (2005) and Mei Gui (2006), where the artist became a singer and musician, turning himself into an African herdsman in one case and a Chinese girl in the other. The process reached its peak in the sound installation Šuillakku (2008), where the experimentation was extended to archeological research, culminating in the philological reconstruction of Sumerian musical instruments and the transformation of the artist himself into an inhabitant of Mesopotamia. He metamorphoses under our eyes, and suddenly we find ourselves catapulted into other worlds and other times, awash in visions and unexpected uncertainties. In this context, I am reminded of experiments in the field of optics, particularly those that concern the self-portrait. It seems that Parmigianino had painted his Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror (1524) to demonstrate his own capacities, presenting himself with the features of an angel and displaying the technical mastery of a demon. Although not created with the same intentions, Cuoghi’s double self-portrait on paper from 2005 illustrates his ability to represent himself, for better and worse. In one of the two drawings, the artist proposes a beautified version of his face, in the other, an uglier rendition. The two drawings are intended to be hung on the same wall, but at a distance of almost thirteen feet. It is impossible to take both of them in at a glance. In the same year, he produced another self-portrait, constructed in this case employing a lenticular technique used to produce three-dimensional images. As we look at it, the work gradually reveals itself as an Arcimboldo-esque divertissement, in which the artist’s face is seen to be composed of an accumulation of toys and dolls. In both works, the gaze is captured once again, in the sense that it is the artist who dictates the conditions of vision.

And what is anamorphosis if not a shifting of the gaze on the basis of a prearranged imposition by an artist on the field of the work? Cuoghi has anamorphosis inside him. The reality that he sees, and we with him, is almost always the least obvious and most obscure. It is no accident that anamorphosis is frequently used to present the image of something we don’t want to see. Consider The Ambassadors, the picture painted by Hans Holbein in 1533 (now in the National Gallery in London). A frontal view of the work offers the compelling image of two diplomats at the height of their human and professional powers. An oblique view presents us instead with the crude representation of a large skull that occupies the foreground. I’m certain that if I went with Cuoghi to the National Gallery he would see the skull at once and find it harder to bring the portraits of the two ambassadors into focus.

On a visit to the Louvre, among the many masterpieces on display, Cuoghi’s attention was caught by a bronze statuette in the department of Assyrian Antiquities. Not even six inches high, the statue is classified as a representation of Pazuzu, a demon associated with the winds, feared but also invoked by the ancient populations of Mesopotamia as protection against deadly threats. Identifying his effigies with the demon himself, the Assyrians were convinced that statuettes of Pazuzu could function as an effective defense for the home, the newborn or people in general. With hybrid features, at once human and animal, the demon is surprising in its dissimilarity from any other artifact produced by the civilization of that region and that time, as well as in its affinities with the most widespread images of the Devil that, from the Middle Ages onward, defined the iconographic representation of evil in the West.

When in 2006 I invited Cuoghi to prepare a solo exhibition for the Castello di Rivoli Museum of Contemporary Art, the artist responded positively, heading straight for Mesopotamia. It goes without saying that I did the same. From one day to the next, I began to see nothing but Nineveh, and then unfortunately Harran as well. I say unfortunately because of all possible times, Cuoghi of course chose the worst, that of the destruction of both cities, just before the entire Assyrian civilization was wiped from the face of the Earth. In this context, Cuoghi created his Pazuzu (2008), a monumental version of the statuette in the Louvre. The work was made using the laser-scanning technique, a precise method of producing prototypes. Appropriating the superstitions of the Assyrians, Cuoghi in fact reiterates the idea that the demon dwells in any of his effigies or reproductions of them. Maintaining the apotropaic function of the original, Cuoghi’s Pazuzu has become an amulet on the scale of the imposing baroque castle that hosts the Castello di Rivoli. Certainly, the demon can protect against evil: the presence of the statue reminds us of its creeping reality, just as Holbein’s skull is a wise memento mori for those who revel too much in the comforts of life. But once again, it is the artist’s eye that commands, that by transporting us elsewhere—in the mental and metaphorical sense, obviously—unexpectedly makes us see a museum in the 21st century as the perfect setting for a monstrous, metamorphic and irremediably irrational presence.