Eva Hesse

dal 12/5/2010 al 31/7/2010

Segnalato da

12/5/2010

Eva Hesse

Fundacio Antoni Tapies, Barcelona

Through her small works, or 'Studioworks', this exhibition shows Hesse's contribution to sculpture's radical transformation at a time when the nature of the artistic object itself was being questioned. The American artist produced a great many small experimental works in a remarkably unusual range of materials. Curated by Briony Fer and Barry Rosen. Contemporary in the exhibition 'Alma Matrix', Bracha L. Ettinger and Ria Verhaeghe show how the forms of representation chosen by both artists generate a common space of concern for others.

Eva Hesse

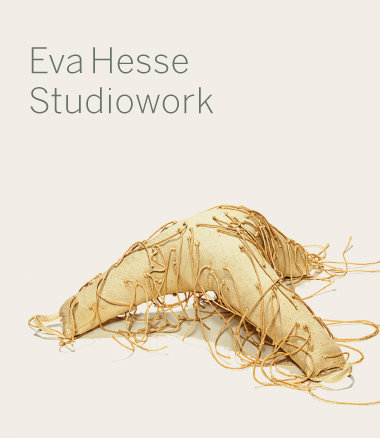

Studioworks

Curated by Briony Fer and Barry Rosen

Although the artistic career of Eva Hesse (1936–1970) lasted only ten years, her production has had a lasting influence on the history of art in the second half of the twentieth century. Through her small works, or ‘Studioworks’, this exhibition shows Eva Hesse’s contribution to sculpture’s radical transformation at a time when the nature of the artistic object itself was being questioned.

Alongside her large-scale sculptures, the American artist Eva Hesse produced a great many small experimental works in a remarkably unusual range of materials, including latex, fibreglass, wire-mesh, cheesecloth, masking tape and wax. These small works have often been called ‘test-pieces’, on the assumption that they were made to test out materials and techniques in preparation for other more ambitious work. However, it is clear that they were rarely only technical experiments. The studioworks show Eva Hesse’s radically innovative use of materials, but they also demonstrate – as a collection-in-miniature of her working methods – her radical transformation of sculpture at a time when the very nature of the art object itself was in crisis. As much as other seminal artists of the 1960s such as Andy Warhol or Donald Judd, Eva Hesse redefined the nature of the aesthetic encounter in a way that still has repercussions for us today.

Eva Hesse. Studiowork

Eva Hesse’s career was abruptly cut short by her tragic death of a brain tumour in May 1970 at the age of 34. She left a studio full of work, both finished and unfinished, as well as many smaller studioworks. In 1979, a large group of these smaller pieces was given by Hesse’s sister, Helen Hesse Charash, to the Berkeley Museum of Art. Others had been given away by the artist herself during her lifetime as gifts to friends such as fellow artist Sol LeWitt. Still more, notably the group of papier-mâché shapes shown in public for the very first time in this exhibition, were simply stored away after her death. The studioworks are made the focus of this exhibition, bringing them back together from diverse collections and placing them in the context of some of her larger pieces.

Hesse’s intense artistic career spanned just ten years in total, but her output has proven to be of crucial importance to the history of twentieth century art. Eva Hesse began as a painter in 1960, having studied at Yale, and only later turned to sculpture. It was in 1965, during a year spent in Germany with her then husband, the sculptor Tom Doyle, that she started to make three dimensional work. At first these were highly coloured reliefs, made of shapes that resembled weirdly textured body-parts – breasts, nipples, penises – combined together to look like wildly dysfunctional erotic machines. Her studio in the German town of Kettwig was in an old disused textile factory where she found abandoned bits of machinery that she combined with string and papier-mâché.

By the time she returned to New York after a year in Europe her work had transformed: it was now strongly sculptural, even when it hung on the wall. Works that were attached to the wall like a picture instead behaved, or rather misbehaved, as if they were so many part-objects, with palpable textures, pendulous shapes and quirky protrusions. In their visceral as well as sometimes comic effects, these objects seemed very far removed from the smooth contemporary finishes of Minimalism. Like a return of the hidden, Hesse brought the sensual bodily qualities of art back into play.

In September 1967 Eva Hesse first began to use latex, which she bought in liquid form from a supplier on Canal Street in Lower Manhattan. Shortly afterwards she started to experiment with fibreglass. These were synthetic materials. But rather than suggest technological or industrial surfaces, Hesse used them to map a radically different bodily topography. Hesse’s work is full of allusions to the body without being a conventional depiction of the body. More and more, as she discovered new materials, she relied on their often bizarre and sensual effects to make the sexual reference for her, rather than incorporate recognisable body-shapes. Although her work is often characterised as ‘organic’ in opposition to the ‘geometric’ vocabulary of the Minimalists, in fact her work tends to disallow straightforward oppositions of this kind – preferring to work with shapes and structures that were both organic and geometric at the same time – as if art were a way of making a contradiction in terms into a material thing.

The term ‘test-piece’ was not one that Hesse herself used to describe her small experimental works. If anything, in her notes, she referred to ‘samples’. The term ‘test-piece’ got attached to them after her death, partly by default. It was – like ‘prototype’ – an expression of the times, revealing a desire to link art with the language of industry. This was a time when artists often had work made by fabricators to their specification, when art was divested of the aura of the individual expressive trace of the artist’s touch. Hesse carried on making smaller objects herself but, like so many artists at this time, used fabricators and assistants to make the large-scale pieces. But the term ‘test-piece’ arguably links her work too much with the technophilia then prevalent, and not enough with its sheer corporeality and bodily associations. The renaming ‘studiowork’ coined in the title of this exhibition is intended as a more elastic term to describe this deeply enigmatic range of objects, which are neither purely technical experiments nor necessarily finished pieces in their own right. They are liminal, falling somewhere between the two and resisting easy categorisation.

The status of the studiowork is precarious. A reasonable definition might be that studiowork is work without necessarily becoming ‘a work’. These are things made by Hesse on a daily basis, handmade and often intricate objects that invite us to think not only about the processes of art but what impulses – both conscious and unconscious – drive the making of art. It might even be that making small things like this in the studio not only provides a way of working things out, of thinking through making, but even prolongs the process of making – deferring an end product in favour of process. The compulsive desire to repeat is evident in much of the studiowork and the techniques deployed by the artist, like threading, folding, cutting, piercing and winding, are often based on repetitive actions and gestures. Looking at the objects is also to see these actions unfolding. Something that initially seems almost accidental and throwaway, like an oddly shaped piece of latex, takes time to look at – and as you look, the gestures that went into making it become clearer. So something that initially looks like a piece of studio debris can come into being as an object as you look at it. The studiowork is at that tipping point between origin and leftover.

There is a photograph of a table in Hesse’s apartment that shows some of the studioworks scattered across the surface strewn with other ephemera, including reviews of her own show at the Fischbach Gallery in 1968, flyers and leaflets for shows by her artist-friends like Carl Andre and Ruth Vollmer, and much else. This photo was actually taken by her friend the artist Mel Bochner as part of an unfinished series of photographs of artist’s work tables – which fitted with Bochner’s own interest in ‘working drawings’ and what he called the ‘upstream of art’ – that is, the work that went into the artwork. Seen from this point of view, the photograph is much more than simply a document of Hesse’s table. It is itself a work that is comparable to Hesse’s studiowork: a work about making work. Hesse’s table was made for her by Sol LeWitt and had a grey grid painted on it. The stuff of art and life that is scattered across it plays out a dynamic of order and accident that characterises all her work.

Of course it is possible to trace links between the studioworks and Hesse’s large-scale works, but this can all too easily explain them away. They can also be thought of in relation to her continuous process of drawing – a practice she maintained throughout her career. This exhibition aims to focus on the studiowork as a group of material objects that deserve attention in their own right, rather than as subsidiary to some other aspect of her work. As such, they reflect her working process, running the gamut between small works, models, samples, partial works, spare parts, trials, fragments, to abandoned bits and pieces. They fall somewhere beneath the threshold of sculpture as it is usually understood. And yet they have the materiality that we associate with sculptural objects. They are part of a history of what can be called ‘sub-objects’ – things that get made in the studio and which are not thrown away but at the same time are not endowed with the imprimatur of a one-off finished piece.

The debris of artist’s studios has a certain allure. Since the late nineteenth century, photographers have exploited the seductive shadows of the studio, from Rodin through to Giacometti, to create the aura of art in the making. However, Hesse’s studiowork, whilst part of a larger historical context of sub-objects, also breaks with the traditional mythology of the studio as a mysterious private realm. For one thing, Hesse herself exhibited some of the little experimental pieces in a glass pastry case at the back of her first major solo show of sculpture held at the Fischbach Gallery in New York at the end of 1968. Alongside the case were some latex buckets and sleeves. This suggests that she wanted them to be seen in public. They had leached out of the confines of the studio to enter the public realm of the exhibition. From now on they had a life outside the studio as well as inside.

Placing the studioworks in glass cases was one way of arranging and showing them. The idea of grouping them together is fundamental to Hesse’s approach to all her work, much of which consists of multiple elements in fairly random arrangements. The accidental look is important. It suggests something more temporary than permanent. Her large-scale work was often made so that it could expand to occupy the space in which in would be situated – the units could be spread out more in a larger space or contract in a small room – or a hanging piece might vary in length according to the height of the ceiling. The distribution of the little test-pieces in the glass cases is simply another version of this: never intended to be fixed but always imagined as fluid and mutable arrangements.

There is a lot of discussion nowadays about the fragility of the materials that Hesse used. This has become an urgent problem for museums and conservators because the works have so deteriorated, especially the latex pieces. To a certain extent, however, the changes wrought by time on the materials were very much part of their appeal for Hesse. She was well aware that latex was a perishable material. She even chose to use it partly because it was – because it meant that it had time built into it. Latex hardens over time and changes colour. Many of the latex pieces, including the studioworks, have turned a deep amber colour and are brittle, as compared with the creamy white and supple material it once was. Depending on how thick it is, a layer can be translucent, but over time it will become opaque. Fibreglass too changes colour, turning from clear and transparent to yellowy green. Although she liked their temporality, it is hard to know what she would have made of their disappearing altogether. The deterioration of the materials can make them look like ruins but it is still possible to get a sense of Hesse’s preoccupations. In particular, Hesse was concerned with light – exactly what makes her materials deteriorate, of course, but which also animates them. Light filters through her materials to different degrees, showing her interest in opacity and translucency.

Over the course of 1969, Hesse worked on a large-scale piece that ended up as Contingent. It was made up of eight separate panels suspended from the ceiling and at right angles to the wall. Each panel was made of a mixture of fibreglass and latex-coated cheesecloth. Each was different from the next and deliberately irregular. During the making of this piece, executed by her assistants, Hesse had to interrupt her work process because of health problems. But she got it done and it was exhibited in a group show at Finch College in New York. She also made other panels associated with it, one of which she gave to her friend Naomi Spector and which is now in the National Gallery of Art in Washington. Although this was always called a ‘test-piece’, it is worth noting that it was a gift and therefore, one might assume, also more than just a test-piece. Naomi Spector herself has always said that she never considered it anything other than a work.

There is another, little known work, which has rarely been shown but which is exhibited here. Considerably longer than the others, the single panel began, according to Hesse’s notes, as part of the larger work but later she decided that it was a separate piece. That is to say, the status of the object changed over time. It began as one thing and became something else. Although it was sold as a separate piece during her lifetime, it is unclear which way round Hesse would have intended to hang it. Or rather, following the logic of her work, it could plausibly be hung either parallel or perpendicular to the wall. The flexibility of orientation is, characteristically, not fixed but open. If the work is viewed from a distance, it almost looks like a materialist antidote to a Rothko painting. It has the same vertical ladder of lighter and darker bands, but instead of layers of paint these are layers of liquid latex painted onto cheesecloth next to sections of translucent fibreglass and polyester resin. Looked at very closely, it is possible to see the irregular grid of the loose weave of the cheesecloth through the latex.

Hesse’s work challenged assumptions about what sculpture should look like but also, through introducing the possibility of multiple orientations, she opened the object to the expanded situation of its setting. This is true of all her work, although it is not only anticipated but is dramatically played out in the often open-ended experiments that make up studiowork, where in many cases it is impossible to say ‘which way around’ an object should go. When Hesse bought some canvas boat bumpers from a marine supplier she covered them with dangling strings like so much pubic hair – making a readymade strange and transforming it into an uncanny object. The three-cornered star shape invites the viewer to think of rotating and touching it. The extreme tactility of the materials does not literally need to be handled in order to incite such a powerful and volatile sense of touch. As a consequence, looking and touching become intimately entwined. This open-endedness is nowhere more apparent than in the paper bowls that Hesse probably made in the last year of her life. These are rather different form her earlier use of papier-mâché, where she moulded newspaper around an inflated balloon and then painted it in a hard shell of enamel paint. In some of these later pieces, strips of paper are laid on in a grid and left bare; in others tissue paper is moulded around a curved shape to make a surface that is barely there.

Some of Hesse’s studioworks are almost viscerally material. Others are almost unbearably ephemeral in their effect. But a powerful logic holds them together – a logic that plays between presence and absence, materiality and immateriality. They may not in the end be ‘test-pieces’ in the sense of that term as it is applied in industrial design. But there is a sense in which they do test out our capacity to see them as sculpture. They are prototypes, not for designs or finished products but of a kind of looking that is full of sense and touch. In this way, the processes of making are translated into the processes of looking. Rather than marginal to the ‘main’ work, the studiowork is at the very heart of Hesse’s approach to making art. It is Hesse at her most extreme, and therefore allows us to see her radical contribution to the history of sculpture.

Contemporary

Alma Matrix

Bracha L. Ettinger and Ria Verhaeghe

Curator: Catherine de Zegher

The exhibition Alma Matrix. Bracha L. Ettinger and Ria Verhaeghe shows how the forms of representation chosen by both artists generate a common space of concern for others, possible connections and shared realities.

In their work, Ettinger (Tel Aviv, Israel, 1948) and Verhaeghe (Roeselare, Belgium, 1950) use images of anonymous persons found in newspapers and archival materials, which they articulate through methods of compilation and techniques of copying, deleting, tracing and painting. As an artist and a psychoanalyst, Ettinger integrates both practices in her work and has developed a peculiar approach to applied psychoanalysis, halfway between artistic and curative practice. Verhaeghe collects, combines and binds her images with the use of computers, or with the type of soft, protecting materials, such as latex or wadding, found in her sculptures.

Image: Eva Hesse, No title (S-117), 1968. © University of California, Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive (gift of Helen Hesse Charash, 1979). Photograph: © Ben Blackwell, Alameda, California

Press Department: Alexandra Laudo

Tel.: +34 934 870 315 / Fax: +34 934 870 009 / E press@ftapies.com

Opening 13 may 2010, 7.30 p.m.

Fundació Antoni Tàpies

Aragó 255, 08007 Barcelona

Opening hours: Tuesday to Sunday, 10 a.m. to 8 p.m.

Mondays closed.

Closed 25 and 26 December, 1 and 6 January.

Admission to the Fundació Antoni Tàpies until 15 minutes before closing.