16/9/2010

Francis Bacon

Two venues, Berlin

It is well known that Francis Bacon often denied that he drew. Since his death in 1992, more and more material has emerged, both from his studio in London and in the hands of various friends and admirers, that demonstrates that he drew throughout his career. The most impressive of these drawings are the series which Bacon presented to his Italian friend and companion Cristiano Lovatelli Ravarino. These seem to be the only drawings the artist made as independent works of art, rather than as preparations for paintings. They are being shown for the first time in Germany, in a joint exhibition at Werkstattgalerie and Galleria Nove.

curated by Edward Lucie-Smith

As everyone interested in Bacon’s work knows, Bacon many times, and often vehemently, denied that he made any use

of drawing. This is contradicted however by an early interview with the critic David Sylvester (Bacon’s most frequent

interlocutor), which is preserved on film. In it, Bacon admits that he does draw, but coyly says that puts his drawings

aside and doesn’t look at them, when the moment comes to paint a picture.

Yet, since Bacon’s lonely death in Madrid in 1992, a mass of evidence has emerged to show that he not only did draw,

but drew prolifically. When he died, for example, a canvas he had just begun was found in his Reece Mews studio in

London. On it was a masterly full-scale drawing for the composition he intended to paint. Numerous scraps of paper

with drawings on them, some mere scribbles it is true, were found when the Reece Mews studio was disassembled, to

be afterwards reconstructed in Dublin.

An even greater mass of material of this type turned up in the possession of Barry Joule, who had evolved from being

Bacon’s neighbor into being his odd-job man and general Mr Fixit. Joule’s account was that Bacon, shortly before his

death, had handed him the drawings, with the words “You know what to do with these, don’t you?” Some people,

knowing of Bacon’s frequent denials that he drew, might have understood this as an instruction to destroy them, but

Joule chose to think otherwise.

While it is true that much of the Joule material is of disappointing quality artistically – a lot of it consists of rough

drawings made on top of photographs torn from books and magazines, with others on top of photos, such as portraits of

Bacon’s old nanny, also for a time his housekeeper, that were very personal to Bacon himself – there are powerful

reasons for accepting it as genuine. One series of drawings in the Joule archive – made on top of illustrations ripped

from boxing magazines dating from the late 1940s - has a direct link to a series of drawings purchased as genuine by the

Tate shortly before the Joule archive emerged. These drawings, also made on top of illustrations ripped from boxing

magazines, belonged to Paul Danquah, a friend with whom Bacon shared a flat in the early 1950s. Danquah, who later

emigrated to Tangier, seems to have given them to Bacon when they were co-habiting.

The Joule material appears to cover a long period, and to be closely linked to a number of well-known paintings by

Bacon. The artist closely guarded access to his studio and it is hard to imagine him allowing anyone, even a boy friend,

to sit there in a corner, manufacturing Bacon related drawings. The two chief consorts of the middle and later years of

his career, George Dyer, an ex-burglar of notable incompetence, who committed suicide in 1971, on the eve of Bacon’s

first major retrospective in Paris; and John Edwards, who though shrewd and loyal, was uneducated, dyslexic and

illiterate, seem particularly unlikely candidates.

The Joule material – and other drawings related to it – have been a permanent embarrassment to a part of the British art

establishment ever since they first made their way into the public gaze.

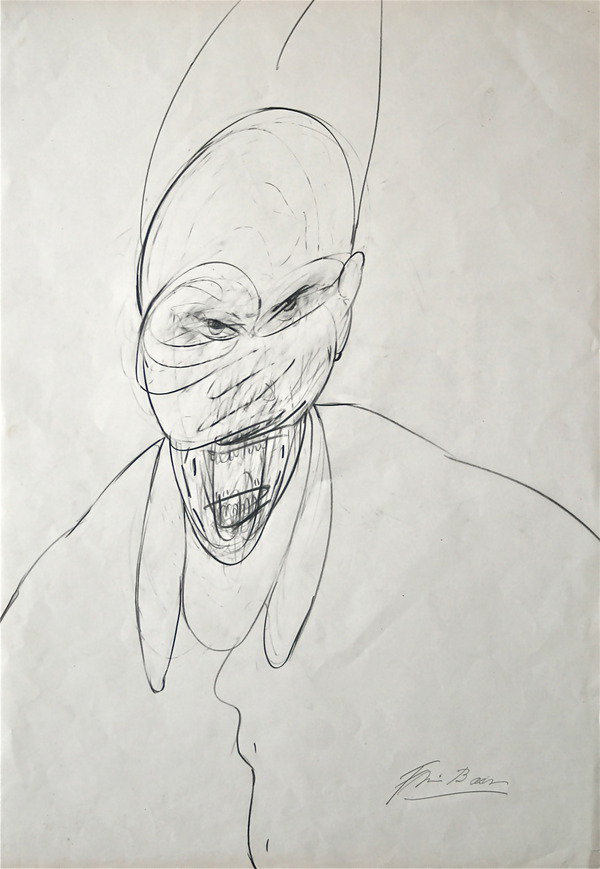

If the material that emerged from Bacon’s studio after his death is problematic because of its lack of real artistic quality,

the same cannot be said of the drawings exhibited in this new exhibition. These are ambitious works, signed and on a

large scale, clearly made as independent works of art. They in many ways seem to sum up the essence of what Bacon

tried to do. Why were they made, and why have they remained at least half-hidden for so long?

The evidence is that Bacon, at the end of his career, found his celebrity increasingly oppressive. His solution was to slip

away to places where he was little known or not known at all, where he could stroll from bar to bar and from restaurant

to restaurant, and amuse himself as he wished. One of his favorite places for escapes of this kind was Italy. A constant

companion in his Italian adventures was a young and handsome American-Italian called Cristiano Lovatelli Ravarino.

There is plenty of evidence that they were often seen together, in locations as different from one another as Bologna and

Cortina d’Ampezzo. The drawings shown are presentation drawings, resembling in this the drawings that the ageing

Michelangelo made for the young Tommaso Cavallieri.

There seem to have been several motivations for making them, apart from Bacon’s desire to commemorate a friendship.

One was simply restlessness. Though happy to get away from the confines of his studio, Bacon still wanted to make art

– but art of a light and portable kind (though not all of the drawings were made in Italy, some appear to have been done

in London). At the end of his life, he wanted to try a new medium, one that had clearly always daunted him. He also

seems to have wanted to correct mistakes made in the past. One striking feature of this series of drawings is that they

recapitulate themes from work made much earlier in his career. Though the drawings belong to the last decade of

Bacon’s artistic activity, their subjects are those that Bacon became associated with in the 1950s – the Popes after

Velazquez and the portraits of businessmen. The Pope images are expanded into a series of portraits of ecclesiastics,

perhaps inspired by what Bacon saw in the streets of Italian towns. There are also portraits of friends and images of the

Crucifixion, a subject that preoccupied the artist throughout his life. Bacon frequently expressed dissatisfaction with the

early works that had made his reputation, and these are an attempt to do better.

Bacon regarded his relationship to Ravarino as unofficial, in the sense that he could never get his friend to commit

himself to something fully public – Ravarino worried what his family would say. He seems to have thought of the

drawings as being essentially unofficial as well. He went to considerable trouble to keep their existence secret from his

commercial representatives, the powerful Marlborough Gallery, who wished to preserve his shamanic persona even

more than he did.

One fascinating aspect of these drawings in that they are the work of a Laocoon, a man struggling hard to escape from

the entwining serpents of his own myth, and to return to the pleasure of making art for its own sake – no other reason

than that.

Edward Lucie-Smith, August 2010

A catalogue with images of 50 drawings and an introduction by Edward Lucie-Smith will be released on the opening

day.

Opening of the Exhibitions: Friday 17th September at 8 pm in the presence of the curator.

Galleria Nove

Anna-Louisa-Karsch-Str. 9, Berlin

Open: Tu-Sa 11-18h

Werkstattgalerie

Eisenacher Str. 6, Berlin

Open: Tu-Fr 12-20h, Sa 12-18h