The Spectacular Art of Jean-Leon Gerome (1824-1904)

dal 17/10/2010 al 22/1/2010

Segnalato da

17/10/2010

The Spectacular Art of Jean-Leon Gerome (1824-1904)

Musee d'Orsay, Paris

The exhibition, the first monograph organised in Paris since the artist's death in 1904, shows all aspects of Gerome's work. It features his paintings, drawings and sculpture, from his early career in the 1840s right up to the very last years, and underlines his special relationship with photography.

Curated by Edouard Papet, Laurence des Cars, Dominique de Font-Réaulx

Jean-Léon Gérôme was one of the most famous French painters of his day. In the course of his long career, he was the subject of controversy and bitter criticism, in particular for defending the conventions of the waning genre of Academic painting, under attack by Realists and Impressionists.

However, Gérôme was not so much heir to this tradition as a creator of totally new pictorial worlds, often based on a strange iconography that favoured erudite subjects and narratives. Painting history, painting stories, painting everything – this was Gérôme's great passion. He intrigued the public with his constant interplay of values and genres, blended in an aesthetic of collage and displacement. His skill in creating images, in presenting an illusion of reality through artifice and subterfuge went hand in hand with paintings that were perfectly finished yet not perfect.

As a very unorthodox academic painter, Gérôme knew how to represent history as a dramatic spectacle and, by creating particularly convincing images, could make the spectator an eyewitness to events ranging from Classical antiquity to his own times.

This exhibition, the first monograph organised in Paris since the artist's death in 1904, shows all aspects of Gérôme's work. It features his paintings, drawings and sculpture, from his early career in the 1840s right up to the very last years, and underlines his special relationship with photography. Supported by Professor Gerald Ackerman's pioneering research in the 1970-1980s, this exhibition does not aim to rehabilitate the artist, but to highlight the paradoxical modernity of an artist who for many years was considered a reactionary.

As a creator of images, he used his artistic skills to develop this technique of presenting an illusion of reality, artificially creating real worlds as in the cinema, and many of his works, disseminated through engraved and photographic reproductions, have become iconic motifs in popular visual culture.

The Neo-Grec circle came about informally in 1847, when a group of young artists, passionate about a new vision of ancient Greece, would meet in the rue de Fleurus. Their approach was meant to be archaeologically accurate, breaking with the approximations of Greco-Roman antiquity current at the time.

At the end of his life Gérôme recalled the atmosphere of this artistic community: “it was the meeting place for all our friends, and there were musicians too. We enjoyed ourselves in a spirit of total harmony. The Neo-Grecs favoured the erudite presentation of intimist or anecdotal subjects. They were immediately criticised for their style, somewhere between a rather cold, formal archaism and a carefully elaborated palette, and reproached for mixing genre painting with history painting as this, along with the precise archaeological details they used so indulgently, was corrupting the classical tradition.

At the 1847 Salon, The Cock Fight announced the arrival of Gérôme as a promising young talent. He was praised as a bold artist for his choices of iconography, although considered by some as a dangerous violator of the conventions of the time. Following the success of this painting, Gérôme soon found himself acknowledged as the leader of this short-lived movement that played an important role in the pictorial revival of the 1840s and the progressive dilution of the history painting genre.

At the 1859 Salon, Baudelaire tackled the thorny issue of the future of history painting: "It uses erudition to disguise a lack of imagination. It is then mostly just a question of transposing scenes of common, everyday life into a Greek or Roman context". The charge naturally led to a critical review of Gérôme's submissions, three of which displayed significant Classical influences: King Candaules, Ave Caesar et The Dead Caesar. It was acknowledged that the painter had "noble qualities", but that he spoilt them by "indulging in didacticism" and by "allowing himself to be distracted". Gérôme's situation is therefore that of an artist in transition, between the decline of Academic history painting, the grand genre with its immutable conventions, and its eclectic reinvention.

This transformation of history painting in Gérôme's work should be seen in relation to two major influences: firstly, Ingres, whom Gérôme admired, and who revisited Greek sources of inspiration through the prism of personal and everyday life; secondly, Delaroche, Gérôme's teacher, who chose a theatrical approach to history painting, presenting it on a more human level, and using anecdote as a way to make great history accessible.

This new style was also in tune with the aspirations of the generation of 1842; the historian Prosper de Barante summed it up as follows: "we all want to know how earlier societies and individuals lived. We demand that they be conjured up and brought alive before our very eyes". In the 1850s, Gérôme responded to this call by starting to develop an unusual balance between documentary illusionism and imaginative reconstruction. In this respect there was really no difference between the painter's Orientalist world and his history paintings. The two sides of his work share the same principle of reconstructing reality to manipulate the narrative potential of the image. Added to this is a smooth, meticulous technique, confirming his ability to make the spectator an eyewitness to the past.

It was this constant balance between historical knowledge, imagination and the "illusion of reality" that decades later would bring such atmosphere to the film productions of Hollywood.

Gérôme was a studio painter. This was where he conceived and composed his pictorial images, working from memory but above all drawing on an imagination steeped in pictorial, literary and theatrical culture. The artist was a collector, particularly of oriental objects probably acquired on his travels. Accounts from the time describe his studio in the boulevard de Clichy as hung about with huge carpets brought back from the Orient. After 1878, when the painter reinvented himself as a sculptor, the studio was no longer just a place of creativity but became the subject of his work. This was quite subtle at first – objects seen on the walls of his oriental settings reflected those hanging on his studio walls – but then became more literal.

Gérôme's fascination with the act of sculpting, with the sculptor's mastery of material and the ability to give it form, drew him to the myth of Pygmalion bringing life to Galatea. This was the image he used when portraying himself as a sculptor in The End of the Sitting], creating an interplay between the redundant presence of the living model and the statue that is taking shape. His works closely combine references from classical mythology with the contingent reality of his studio.

We do not know when exactly he thought of bequeathing the photographic reproduction rights of all his work to the Bibliothèque Nationale – the French national library. But he once wrote to a collector “I am keen to have as complete a collection of my works as possible, given that I have bequeathed it to the Bibliothèque Nationale". Gérôme had a beautiful collection of large-scale photographs produced, showing his sculpted works in the studio. He also had himself photographed with some of them.

In 1859, Gérôme struck up a friendship with one of the greatest art dealers of his time, Adolphe Goupil, and went on to marry one of his daughters, Marie, in 1863. Goupil was also a founder of the art publishing house that bore his name. His stroke of genius was to bring together, from 1846 onwards, the booming market in art reproductions and that in original paintings.

Gérôme's master, Delaroche, was one of the first artists for whom the widespread system of reproduction – first using engraving then photography – was introduced. Gérôme later succeeded in taking full advantage of this. Thanks to this system, images of works that had been briefly exhibited at the Salon were mass-produced and circulated increasingly rapidly throughout the world, reaching new audiences. This market in reproductions brought more fame to the artist while at the same time generating handsome profits.

Il eut aussi des retentissements esthétiques considérables. Aesthetically too, there was a significant impact. The circulation of reproductions of painted works through engravings and photographs also altered the status of the representation. The subject was transformed into an image that was even more successful when the salient points of its narrative were clear, underlined and highlighted.

As Emile Zola ironically pointed out, "Clearly Monsieur Gérôme works for the House of Goupil. He makes a painting so that it can be reproduced through photographs and engravings and sold in thousands of copies." Indeed, the artist would often rework or copy a painting to facilitate its reproduction.

Because of their wide circulation, some paintings became internationally known images, embedded in the popular imagination, while original paintings, such as The Duel after the Ball, were kept in private collections.

After 1855, Gérôme undertook numerous trips to the eastern Mediterranean, this not too distant "elsewhere" which, in the mid 19th century, lay beyond Greece. He made it the subject of many of his works.

His Orientalist works are quite curious. Drawing on the pictorial and literary imagination of his time, Gérôme invented oriental scenes, using meticulously accurate detail and his open recourse to photographs taken during his trips to disguise his strategy. The Orient that Gérôme depicted was dreamed up by Victor Hugo in 1829 in his poetic work Orientales, and his "authentic" images at that time confirmed a view of the Orient as a place of sensuality and violence. In 1863, a critic described the sinister excursion on the Nile depicted in The Prisoner: "All aspects of the Orient are there - its implacable fatalism, its passive submission, its eternal tranquillity, its brazen insults and its ruthless cruelty".

Gérôme's "accurate" images seemed even more genuine as they unfailingly recreated the Orient that his contemporaries expected. They brought a stamp of authenticity to this fantasy. Gérôme, however, took many liberties, and few of his works are the result of direct observation. The purported historical, geographical or ethnographic settings in the majority of his paintings do not stand up to close analysis.

Gérôme succeeded in painting an image of the Orient that was immutable, untouched, and presented for a western audience. He thus managed to captivate a public that delighted in fixed images of an unchanging "elsewhere".

Gérôme became interested in three-dimensional work very early on, but he was fifty-four and already successful when he turned to sculpture, bringing to it all the seriousness and enthusiasm of a young artist. He soon came into close contact with famous sculptors (Bartholdi, Fremiet), and in 1878, presented The Gladiators, his first sculpture. This "archaeological" monument makes no concessions, and picks up the motif of the central group in Pollice verso.

This first stage in a constant cross-referencing of painting and sculpture that continued until the end of his career, was consistent with the aesthetic of Academic realism prevalent at that time, and confined to the monochromy of bronze, sculpture's noble material.

It was after 1890, with Tanagra, that there was a radical change in Gérôme's work, a shift towards polychromy, the great challenge of his sculptural oeuvre. The application of colour to modern sculpture, in imitation of ancient sculptures, had aroused fierce debate during the first half of the 19th century: Gérôme, irrepressibly curious, saw this as a way to revive the discipline. He displayed the full extent of his skills when painting marbles, using paint made from pigmented wax that he felt was closer to those of antiquity.

Gérôme's striking, illusionist simulacra blurred the boundaries between popular and Academic polychromy, and, at the start of the 20th century, unequivocally posed the question of the limits of representation. This daring and uninhibited use of colour and the conscious eroticism of these painted marble sculptures attracted the most vehement criticism to Gérôme's modern "idols". At the end of the 1890s he devoted more and more of his time to sculpture, while regularly producing statuettes for reproduction (Napoleon entering Cairo, Tamerlane). Gérôme was working on a sculpture when he died - Corinth, his most spectacular and his artistic testament.

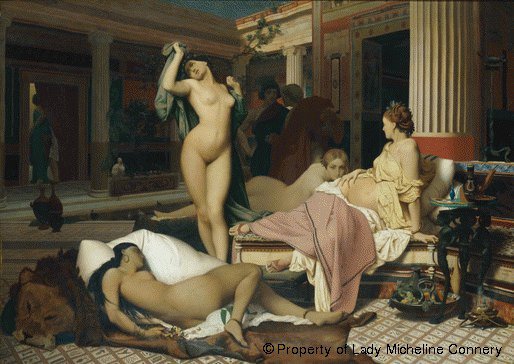

Image: Jean-Léon GérômeGreek Interior, The Women's Apartments

© Property of Lady Micheline Connery

Opening 18 October 2010

Musée d'Orsay

1, rue de la Légion d'Honneur, 75007 Paris

Tuesday to Sunday: 9.30am - 6pm, Thursday till 9.45pm