Three exhibitions

dal 3/11/2010 al 25/11/2010

Segnalato da

Ogawa Haritsu

Fu Shan

Ting Yun p'eng

Wu Pin

Minko of Tsu

Shokado Shojo

Hakuin Ekaku

Suio Genro

Kishi Ganku

Nagasawa Rosetsu

Tanaka Totsugen

3/11/2010

Three exhibitions

Sydney L. Moss, London

The first exhibition: 'Chinese paintings and calligraphy' is devoted to Chinese paintings and calligraphy, the second to a private collection of Japanese lacquer, particularly inro, while the third presents Japanese works of art including matched smoking sets or tabakoire, Japanese painting and a dazzling array of works by Ogawa Haritsu (also known as Ritsuo) showing the full range of this versatile artist's ability.

Sydney L. Moss Ltd. is celebrating its centenary with three exhibitions this autumn, one devoted to Chinese paintings and calligraphy, the second to a private collection of Japanese lacquer, particularly inro, while the third presents Japanese works of art including matched smoking sets or tabakoire, Japanese painting and a dazzling array of works by Ogawa Haritsu (also known as Ritsuo) showing the full range of this versatile artist’s ability. All three will be on view to the public at 12 Queen Street, London, from 4 to 26 November 2010, coinciding with Asian Art in London (4 to 13 November).

The gallery has finally published its long-trumpeted definitive survey of literati Chinese paintings and calligraphy, This Single Feather of Auspicious Light, a set of four large volumes accompanied by life-size fold-outs of three handscrolls, all presented in an embossed cloth box and weighing in at 28 kg or 62 lbs – the largest art dealer’s catalogue ever. A selection of the works featured in the book will be on show including a horizontal poem-letter, mounted as if for tea ceremony display in a tokonoma, by Fu Shan who was one of the great early Ch’ing calligraphers, as well as being the intellectual and literati hero of Shansi province. His personal, small-scale, intimately modulated handwriting is relatively rare. Portraiture has until recently been a largely ignored aspect of old Chinese painting, unless you were the Emperor; but this publication champions the significance of superior figural painting evident in the remarkable study by the leading court artist Chiao Ping-chen of a Tibetan lama-king, probably a posthumous devotional study. Dating from the early 1720s, it is most likely to have palace workshop connections.

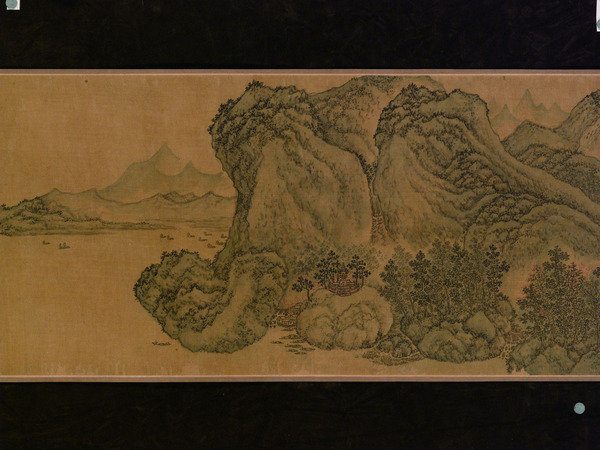

One of the more important handscrolls on view is Ting Yün-p’eng’s Kuan-yin in her Compassion Barge, a single-hair brush ink fine-outline masterpiece datable to the very early 1580s, in which the deity and the dharma are supported and protected by a full complement of Buddhist lohan and other protective divinities, notably including those of a Taoist persuasion. The exotic lohan float from the Isles of the Blessed upon a range of magical sea creatures, all of which allows plenty of room for the gifted artist’s imagination, as well as his astounding technical prowess. Another rare and important handscroll is that of Wu Pin’s Peach Blossom Spring, datable to circa 1615-20. The late Ming dynasty’s arch-fantasist is here characteristically less hard-edged and bizarrely dramatic than he is in his huge hanging scrolls, but the result is no less unlikely and unsettling. The Peach Blossom Spring story of a lost paradise free of government intervention takes place on a series of three islands. Wu’s deliberately naïve architectural details inhabit a landscape which is at once charming and innovatively radical, both in overall composition and in its strange, unconventional brushwork.

The other two exhibitions will be devoted to Japanese art, the first being the collection of Californian nonagenarian and grande dame of the heyday of the Los Angeles Japanese art collecting scene, Elly Nordskog, from which Sydney L. Moss is offering 65 inro, 30 pipecases, 60 netsuke and a selection of other works. Mrs. Nordskog showed exceptional taste in Japanese lacquer, especially in marrying inro with netsuke of complementary subjects. She collected with an unerring eye for the exquisitely beautiful, especially her inro. In addition she was drawn to pipecases, a somewhat neglected area of collecting, but one that is immensely rewarding in terms of the quality of the workmanship of the lacquer (and related arts). She also collected netsuke, unsurprisingly with a marked preference for lacquered examples. Sydney L. Moss has researched both inro and pipecases as the existing literature on inro does not fully explain the symbolism and source derivation, and – inexplicably – there is no book on pipecases. The accompanying catalogue is intended to make a contribution to the general understanding of the background and meaning of these beautiful works of art. The gallery has been assisted in its endeavours by the husband and wife team of Heinz and Else Kress, who have personally inspected and archived 33,000 inro, making them the world’s most experienced connoisseurs of the field. Translators have also been driven to the verge of insanity with persistent questions.

The third exhibition springs in part from the second. This centenary catalogue reflects the gallery’s tastes and enthusiasms in Japanese art, not least for robustly individualist artists of character, mostly of the Edo period. The Nordskog collection does not particularly focus on the pouches associated with pipecases – in other words the matched smoking set, tabakoire. These have long been prized by Sydney L. Moss and a select group of Japanese collectors. On view and published in detail are six matched sets, with extensive interpretations of the imagery and poetic associations of the different elements: pipecase, motifs printed or stamped on the pouch, metal clasp and backplate. These smoking sets lead to a rare grouping of tonkotsu, wood portable hanging tobacco containers, considerably earlier and more rustic in feel than the cloth and leather pouches, but frequently the work of netsuke carvers, in this case many by Minko of Tsu, with lavish use of inlays in different materials. One such is the work of Minko’s follower, Hasegawa Ikko; and that is the connection to a number of other works by him, notably the remarkable pipecase inlaid with hares.

Wood and lacquer objects with exotic inlays are also prominent in this exhibition, the crowning glory of which are several important works by Ogawa Haritsu known as Ritsuo, (1663-1747), one of the great Japanese masters of the applied arts, still curiously misunderstood and underrated, especially in his own country. Acquired some years ago with the centenary in mind is a pair of cedar sliding doors decorated with toppled piles of open books as well as major sculptures by him; a gold-lacquered and inlaid figure of a crouching Benkei, and a pair of part-lacquered wood Nio temple guardians, a major rediscovery. In addition to these important works, each unique to date, there is a fascinating box by him, decorated in a brilliant and bewildering variety of inlays and lacquer techniques with his own and other early inrō and sagemono types. Also on view are a number of rare and admirable “special” works by his follower, Mochizuki Hanzan (1743?-1790?).

This exhibition also focuses on a few paintings by Ritsuo, which serve as a link to a major section of paintings and calligraphies by other artists. The majority of them derive from and illustrate the Edo period’s fascinating sub-stratum of Chinese-influenced and Confucian taste and aesthetic content, to which in Japan only a handful of sencha (steeped tea ceremony) and late bunjinga (the literary men’s painting) adherents pay much attention; while in the West, hardly at all. A small but significant group of calligraphies by the great Ishikawa Jozan (1583-1672), master of the Kyoto Chinese-style retreat Shisendo and hero of the excellent publication of the same name, includes a letter to his friend Hayashi Razan (1583-1657), the leading Confucianist of the day, comparing Razan to the 36 Chinese poets after whom he named his retreat. The catalogue includes an essay on Jozan, Ritsuo and Edo period Confucianism, its relationship to the Shogunal government and the artistic themes and directions involved, by the noted Chicago collector and enthusiast Dr. Edmund J. Lewis.

Noteworthy Zen paintings by Shokado Shojo (1584-1639), Hakuin Ekaku (1685-1768) and a chinso portrait of Hakuin’s abbot friend Kokoku with a long eulogy by Suio Genro (1717-1789) are also on show. Other paintings featured are largely defined or categorised, where they can be, by their quirkiness of appeal, and include surprising works by Kishi Ganku (1749/56-1838), Nagasawa Rosetsu (1754-1799) and the charming Tanaka Totsugen (1768-1823).

Any Sydney L. Moss Japanese art catalogue would be incomplete without new groundbreaking netsuke discoveries, and visitors to the gallery will find two important putative works by an artist named Mataemon, recorded but with no work illustrated in the important 1781 publication Sōken Kishō.

The exhibitions coincide with the 13th staging of Asian Art in London (4 to 13 November 2010), an annual event that unites London’s leading Asian art dealers, major auction houses and societies in a series of selling exhibitions, auctions, receptions, lectures and seminars that attract visitors from around the world.

Publications:

This Single Feather of Auspicious Light: Old Chinese Painting and Calligraphy

The Elly Nordskog Collection of Japanese Lacquer

Sydney L. Moss Ltd. Centenary Exhibition of Japanese Works of art

Image: Detail from Wu Pin (active c. 1583-1626), Peach Blossom Spring, c.1615-20

For information:

Sue Bond Public Relations

Hollow Lane Farmhouse, Thurston, Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk IP31 3RQ, UK Tel. +44 (0)1359 271085, Fax. +44 (0)1359 271934 E-mail. info@suebond.co.uk

Opening Thursday, 4th November, 2010

Sydney L. Moss Ltd.

12 Queen Street, London W1J 5PG

Hours: Monday to Friday, 10 am to 5.30 pm

Mayfair late-night opening Monday 8 November to 9 pm

Free admission