Two exhibitions

dal 6/3/2011 al 17/9/2011

Segnalato da

6/3/2011

Two exhibitions

Metropolitan Museum of Art - MET, New York

Works featured in 'Reconfiguring an African Icon' are highly creative re-imaginings of the iconic form of the African mask. Among them are sculptural assemblages made of incongruous combinations of discarded materials by two contemporary artists from the Republic of Benin, Romuald Hazoume' and Calixte Dakpogan. Featuring about thirty Andean tunics drawn 'The Andean Tunic, 400 BCE-1800 CE' examines the form of the tunic, which held an important cultural place in Andean South America for centuries, particularly in Peru and northern Bolivia. Textiles, a much developed art form there in ancient times, were themselves valued as wealth, and tunics were among the most treasured of textiles.

Reconfiguring an African Icon: Odes to the Mask by Modern and Contemporary Artists from Three Continents

March 8 - August 21, 2011

Gallery between Michael C. Rockefeller and Lila Acheson Wallace wings, 1st floor

curated by Alisa LaGamma and Yaëlle Biro

Highly creative re-imaginings of the iconic form of the African mask comprise a unique installation to be held at The Metropolitan Museum of Art beginning March 8. Featuring 20 works of art—19 sculptures and one photograph—Reconfiguring an African Icon: Odes to the Mask by Modern and Contemporary Artists from Three Continents reflects on the enduring relevance of African masks as a source of inspiration for artists across cultures into the present. Highlights of the installation will be whimsical sculptures created from discarded consumption goods by contemporary artists Romuald Hazoumé (b. 1962) and Calixte Dakpogan (b. 1958), both from the Republic of Benin. Seventeen of the 20 works selected are on loan from European and American private collections; the others are drawn from the Museum's own collection.

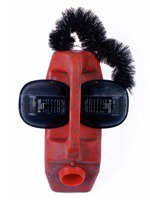

Works by Hazoumé and Dakpogan featured in the installation are self-consciously ironical references to the fact that the mask is the African form of expression most renowned in the West. Hazoumé's signature works on view, including Ear Splitting (1999, CAAC, The Pigozzi Collection, Geneva), are faces created from plastic gasoline jerricans, to which features made from a variety of scrap matter are added. The artist conceives of his "jerrican masks" as an homage to West Africa's masquerade traditions. They also function as portraits of contemporary Beninese society with a humorous twist, as well as layered and multifaceted reflections on the relationship between Africa and the West.

Dakpogan, represented in the installation by Heviosso (2007, CAAC, The Pigozzi Collection, Geneva), draws upon such disparate media as metal from abandoned cars, CDs, combs, and soda cans. The descendent of royal blacksmiths of Porto-Novo in the Republic of Benin, he creates ingenious sculptural compositions that reflect upon coastal Benin's long history of exchanges, which have defined its religious and political history. Consciously invoking the mask's importance as it relates to regional expression and to its centrality to the art historical canon, Dakpogan reflects on this status through a highly inventive synthesis of unexpected yet familiar elements.

The installation will also include explorations by modern and contemporary American artists in a variety of media to demonstrate further the open-ended potential of the seminal "mask" for dynamic reinvention. Works on view will include the iconic photograph Noire et Blanche by Man Ray (1890-1976), recent works by influential sculptor Lynda Benglis (b. 1941), and composite creations by Willie Cole (b. 1955). While Benglis's longstanding interest in African sculpture was the source of inspiration for a series of masks in glass shown here for the first time, Cole pays tribute to classical genres of African masks through assemblages of humble material drawn from his own environment that allow him to reflect on his spiritual attachment to Africa's material culture.

Reconfiguring an African Icon is a collaborative curatorial project organized by Alisa LaGamma, Curator, and Yaëlle Biro, Assistant Curator, both of the Department of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas, in association with the Department of Nineteenth-Century, Modern, and Contemporary Art. Exhibition design is by Michael Batista, Exhibition Design Manager; graphics are by Kamomi Solidum, Associate Graphic Designer; and lighting is by Clint Ross Coller and Richard Lichte, Lighting Design Managers, all of the Metropolitan Museum's Design Department.

A podcast featuring voices of artists represented in the installation as well as different curatorial perspectives on their work will complement an extended web feature on the Museum's website at www.metmuseum.org.

----------------------------------------------------------

The Andean Tunic, 400 BCE – 1800 CE

March 8 – September 18, 2011

The Michael C. Rockefeller Wing, 1st floor

curated by Julie Jones and Ann Pollard Rowe

The Metropolitan Museum of Art will present a special exhibition focusing on the Andean tunic, beginning March 8. Featuring some 30 tunics drawn from the Museum's collection with loans from The Textile Museum, Washington, D.C., The Cleveland Museum of Art, and two private collections, The Andean Tunic, 400 BCE – 1800 CE, will examine the form of the tunic, essentially a type of shirt, which had an important cultural place in Andean South America for centuries. Textiles, a much developed art form there in ancient times, were themselves valued as wealth, and tunics were among the most treasured of them.

The exhibition is made possible through the generosity of the Friends of the Department of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas.

The ancient peoples of northwestern South America are renowned today for their great abilities as weavers, dyers, and designers of textiles. The primacy of cloth was established with the beginnings of civilization in the region that is now Peru, when manipulating fibers into functional, and decorated, fabrics and fiber objects began. Their multiple uses remained integral to Peruvian society and invaluable to Peruvian peoples as a mark of indigenous wealth and identity until the 18th century, long after the advent of European authorities and colonists. Among the textiles produced during those many centuries were garments. Gender specific, the garments generally conformed to basic types. For men, that meant a tunic, mantle, loincloth, and headcovering. Tunics, shirt-like garments sewn up the sides and open at the neck, were the most significant of them. Tunics occupied a meaningful cultural place for centuries as markers of prosperity, place, and status.

The earliest works in the exhibition will be two tunics dated to the fourth century BCE from the Ica valley in southern Peru. One, of beige cotton with a pattern of double-headed serpents, and the other of camelid hair with a supernatural figure on the rich red-brown ground, illustrate the possibilities of surface, color, and design that the two fibers offer. The cotton tunic is its natural hue, as cotton does not dye well, whereas the tunic of camelid hair, which dyes very well, is splendidly colored—there are four Andean camelids: the domesticated llama and alpaca, and the wide vicuña and guanaco. Their hair was spun into yarn for the making of textiles and fiber objects of all sorts.

Another early tunic is one from Peru's Paracas Peninsula, the site of a major archaeological find of the early 20th century. The tunic, from the collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art, is a deep green with many repeated images of double-headed birds (ca. 300-100 BCE) worked in red with heightened details of yellow. The double-headed birds are done in inventive design units, almost in a theme and variation manner, while the whole conforms to a solidly rectilinear plan. A few hundred years later in the Andean altiplano further south, an impressively red Pucara tunic with large shoulder panels (ca.135-525 CE) was as significant a presence then as it is today. Unusual in structure, the inset shoulder panels are oriented horizontally with a yellow, red, and blue face in the center. The face, which is surrounded by short rays, may represent a deity, perhaps that of the sun. The imagery appears to be an early form of iconographic patterning that, while it changed, would nonetheless endure for some centuries.

The largest tunic in the exhibition (ca. 580-680), with a width of more than five feet at the shoulder, is thought to come from Peru's Arequipa area; it is composed of several horizontal, tapestry woven panels including two with "deconstructed" patterns. The panels are made up of proliferating, ribbon-like elements that do not repeat, reverse, or form legible patterns, yet without any apparent organization the elements are well balanced both internally and within the tunic as a whole. Tunics of this size were probably not worn in life but were reserved for the wrapping of the honored dead. The large tunic can be contrasted with the miniature tunic (ca. 800-850) that is the smallest work in the exhibition, with a shoulder width of barely 10 inches; its imagery is characteristic of the Wari style, including profile staff-bearing figures.

Northern tunics differ in shape from those further south. They are shorter—only waist length—and most frequently have sleeves. Frequently, too, they have elaborated surfaces. Those of the Chimu kingdom centered in the Moche valley had such elaboration as seen in a very red tunic that is completely covered with tassels (ca.1100-1250). The exhibition will include an outstanding work made with an abundance of camelid hair dyed with cochineal, an intense colorant extracted from insects; the tunic has a number of small, brightly colored figures all but hidden beneath the red tassels. Another Chimu tunic on view with an extraordinary surface will be a gauze weave cotton brocaded with pelicans (ca. 1400-1500). Lent by The Textile Museum in Washington, D.C., it is made of finely spun cotton and is virtually transparent. The pelicans, in profile on the front and back of the tunic, have a prominent place in Chimu imagery. Peruvian pelicans are shore birds abundant along the Pacific coast.

The Inkas invaded the Chimu kingdom on the northern Pacific coast late in the 15th century. They had begun their conquests only in the 1430s, and by 100 years later, when the Spaniards arrived in Peru, much of northwestern South America had been incorporated into their empire. Disciplined and focused, the Inka sense of control can even be seen in their tunics. Inka tunics exist in some numbers today and are known in standard formats of highly geometric plans. An excellent example on view will be one in a checkerboard pattern (ca. 1460-1540) with a motif in each square that adds to the complexity of its visual effect. The motif is an emblem known as tocapu, one of the enigmatic Inka symbols elaborated on works of art. The motif is present on another tunic in the exhibition dating to the 17th century.

The tunic continued to be worn under Spanish colonial rule on special occasions. Members of Inka royalty and their descendents had that privilege. The red yoke and the tocapu in the 'V' and at the waist are Inka regal symbols, while the rampant felines at the neck are European. Incorporating elements of the two symbolic systems, the Andean and the European, emphasized the social status and importance of the wearer. By the 1780s, however, such tunics were feared by church fathers and colonial administrators alike. They had the ability to raise memories of a heroic Inka past, so the wearing of tunics was prohibited.

Education programs organized in conjunction with the exhibition include screenings of documentaries by photographer and musicologist John Cohen about the culture, music, and textile history of indigenous Andean peoples. Gallery talks will also be offered for general audiences.

The exhibition is organized by Julie Jones, Curator in Charge of the Department of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas at the Metropolitan Museum; with Ann Pollard Rowe, Research Associate, Western Hemisphere Textiles, The Textile Museum, Washington, D.C., who is curatorial consultant to the exhibition. Exhibition design is by Daniel Kershaw, Exhibition Design Manager; graphics are by Norie Morimoto, Graphic Designer; and lighting is by Clint Ross Coller and Richard Lichte, Lighting Design Managers, all of the Metropolitan Museum's Design Department.

It will be featured on the Museum's website at www.metmuseum.org.

Image: Romuald Hazoumé (Beninese, b. 1962). Ear Splitting, 1999. Plastic can, brush, speakers. Courtesy CAAC–The Pigozzi Collection, Geneva. © Romuald Hazoumé

The Metropolitan Museum of Art Press Office

telephone 212-570-3951, or fax 212-472-2764, communications@metmuseum.org

Opening Monday, March 7, 10 a.m. - noon

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

1000 Fifth Avenue at 82nd Street, New York

Hours: Tuesday–Thursday 9.30 a.m.–5.30 p.m.*

Friday and Saturday 9.30 a.m.–9 p.m.*

Sunday 9.30 a.m.–5.30 p.m.*

Closed Monday (except Met Holiday Mondays**), Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year's Day

Admission: Adults $20, Seniors (65 and older) $15, Students $10

Members (Join Now) Free, Children under 12 (accompanied by an adult) Free