Two exhibitions

dal 6/4/2011 al 5/5/2011

Segnalato da

Kaoru Arima

Daan van Golden

Heather Guertin

Charline von Heyl

Matt Hoyt

Amy Lien

Erik Lindman

Jason Loebs

Pete Mandradjieff

Carissa Rodriguez

Julia Rommel

Terry Winters

Anicka Yi

Morgan Fisher

Richard Aldrich

6/4/2011

Two exhibitions

Bortolami Gallery, New York

At the gallery II an exhibition of Morgan Fisher's new works, photographs and works on paper. At the gallery I 'Addicted to Highs and Lows' group show, curated by Richard Aldrich.

Gallery I:

Addicted to Highs and Lows curated by Richard Aldrich

curated by Richard Aldrich

Kaoru Arima, Daan van Golden, Heather Guertin, Charline von Heyl, Matt Hoyt, Amy Lien, Erik Lindman, Jason Loebs, Pete Mandradjieff, Carissa Rodriguez, Julia Rommel, Terry Winters, Anicka Yi

A writer (theorist) or a curator is a kind of artist. They know (unconsciously) what they are looking for. They are drawn to things, and need only to take what they have seen and contextualize it in their own way, use it their own way to make sense and begin to articulate their own feelings. Thus two readers, after finishing the same book, have two separate ideas of the book. And this is the best thing: these same two readers could meet again in ten years and reread the same book and have two new ideas. Marriage is the desire to have a mirror to gauge oneself everyday: "what did you think of that?" you could say to your spouse. Or often you don't even need to say anything. This is why art is so important, something to look at and use to recognize and construct how we are feeling. This is why art needs to be so free, and this is why the artist that writes has become out of date. It is always changing: the 50s painters distrusted Motherwell because he had gone to school. The minimalists lauded Smithson because he wrote such good jokes. These days the primacy-of-writing mentality still exists (but without the good jokes). This has come to represent our avant-garde: a press release. But even Proust was laughed at as a writer of soap-operas. We work from our past, and history sorts it all out. Maybe this is the market, which really just means "how do we cover up their insecurity?" so of course a witty text (press release) is a good idea, or an opaque one for the obvious reason (they are a genius exclamation point exclamation point exclamation point).

There is a good joke that a cop finds a drunk stumbling around in front of a lamp post. The cop says to the drunk, "what are you doing?" The drunk says, "I lost my keys in the alley and am trying to find them." The cop says, "If you lost them in the alley why are looking out here by the lamppost?" To which the drunk replies, "the light is better out here."

There is a sort of making that is responding to life and there is a sort of making that becomes a means of not getting at true feelings, a distraction, conscious or otherwise, that often comes from fear. The intellect often serves this purpose as does a reliance on it to legitimize or rationalize our actions and our desires rather than acknowledge them for what they are. It is always easier to stay in the light, to not stare into the abyss*, but where is this getting us?

I guess what I am saying is that it is into this abyss that I find these artists staring. The work varies in aesthetic or social connection, but that is the point too. There isn't a "look" to an internal conflict. We still see minimal, we still see abstract, we still see conceptual, and we hold these aesthetics to some structure of meaning or history, but isn't the main precept of our day that the ways in which we get information is just as important as that information? What is important here is that the connecting tissue isn't a signifier or formal quality or relation to cultural production, but rather the similar, less delineated strain of, say, intention or a self contextual-framing; or an emotional kinship in an approach to working regardless of whatever the eventual object is.

(Richard Aldrich)

----

Galley II:

Morgan Fisher

New Work: Photographs and Works on Paper

Bortolami is pleased to announce an exhibition of Morgan Fisher's new works, photographs and works on paper.

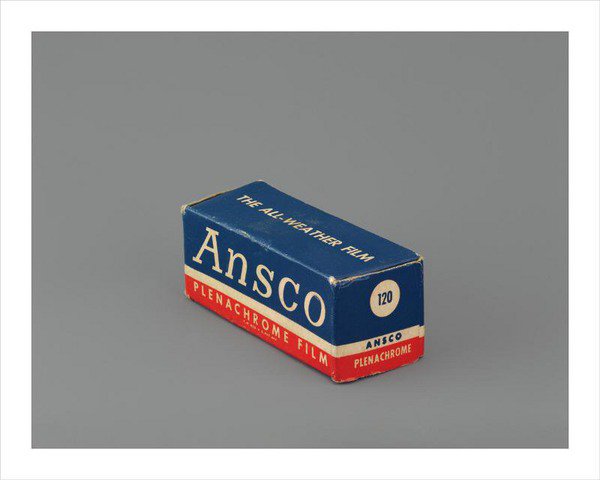

The photographs in the show present boxes of still film from the 1950s. They are doubly obsolete: once for being drastically past expiration, and twice for being a medium that is no longer in popular practice. The '50s was the decade when Fisher became aware of photography and started taking photographs. Beyond being obliquely autobiographical, the photographs are acts of remembrance, and as such they resemble acts of mourning. They take note of film's passing away, not literally dying because it does continue, but gradually passing out of use and out of consciousness. The photographs also suggest the power of obsolescence to disturb. The boxes are relics of a market that no longer exists, chance survivors of a system of production, distribution, advertising, and consumption, in which for whatever reason they did not fulfill their intended purpose, to be used. They express the pathos of the unrealized: intentions, expectations, and hopes. Even though the film boxes survive as they were made, by remaining unused they are an expression of waste.

The works on paper are rubbings made of the covers of a British photography annual, Photograms of the Year. Photography annuals are the last gasp of the salon tradition in photography, in which a photographer is represented by only one photograph. The photographs in these books are pleasing pictures of pleasing subjects and show the utmost technical skill, but few are what we could call original. They are stereotypical subjects treated by stereotypical means: moody Venice, yachts under sail, picturesque streets in poor villages, soulful children, ebullient children, nudes (female of course) in poses and embellished with props that sometime raise them to the level of kitsch, the mysterious East, represented by men with wrinkled faces and young women, clothed and unclothed, usually accompanied by props that make sure we don't miss the point. Classical photographic modernism, even then in its late stages, is absent from these pages, instead there are the last moments of pictorialism. The photographs reflect an unhappy period when photography was unable to advance beyond its then recent past, and necessarily oblivious of the radical shift that was to come a few years later and consign such photography to the irrelevant. A rubbing is a kind of touching that expresses devotion. A classic subject for a rubbing is a tombstone.

Morgan Fisher lives and works in Santa Monica, California. A survey of his work, including films, works on paper, paintings and painting installation, is currently on view at Raven Row in London. He has had solo exhibitions at MoCA Los Angeles; The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York ; Tate Modern, London; and Kunstverein Hamburg. He started making films in the late 1960's, and in the early 1970's worked occasionally as a film editor in Hollywood. Since the late 1990's his work has been mainly in painting and recently installation, both painting and architectural. He has taught at Brown University, California Institute of the Arts, and the University of California, Los Angeles.

Image: Morgan Fisher, Ansco Plenachrome Film 120 March 1956, 2011, C-print, 16 x 20 inches

Opening April 7th, 2011 6 to 8pm

Bortolami Gallery

510 West 25th Street - New York

Gallery Hours: Tuesday – Saturday 10am – 6pm