Hokusai

dal 24/8/2011 al 30/10/2011

Segnalato da

24/8/2011

Hokusai

Martin Gropius Bau, Berlin

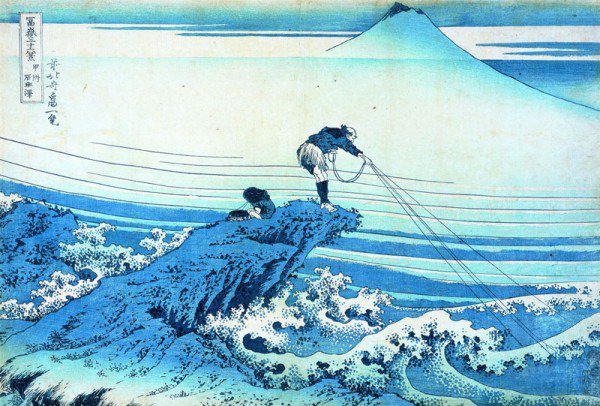

For the first time in Germany a major retrospective is to be devoted to the world-famous Japanese artist Hokusai. Over 350 loans, which with few exceptions come from Japan, will be on display: works from all periods of the artist's career - woodcuts and drawings, illustrated books, and paintings. Curated by Nagata Seiji, the leading Japanese authority on Hokusai and his work.

Curated by NAGATA Seiji

For the first time in Germany a major retrospective is to be devoted to the world-famous Japanese artist Hokusai (1760–1849). Perhaps his best-known picture is the woodcut: “The Great Wave off Kanagawa” from the series: “Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji” (1823–29). Over 350 loans, which with few exceptions come from Japan, will be on display in the exhibition in Berlin’s Martin-Gropius-Bau. NAGATA Seiji, the leading Japanese authority on Hokusai and his work, will be curating the exhibition, which is to be seen exclusively in Berlin. Works from all periods of the artist’s career – woodcuts and drawings, illustrated books, and paintings – will be shown.

In 2000 Life Magazine ran a survey to find out who were the most significant artists in world history. Hokusai came 17th, ahead of Picasso. The exhibition – which covers the entire span of Hokusai’s creative activity, extending well over 70 years – offers convincing evidence of the genius of this great artist. In the course of his life he used over thirty pseudonyms. Today he is known to the world under just one of these names: Hokusai. His full name was Hokusai Katsushika.

Hokusai was born in Honjo, a district of Edo, in 1760. Today Honjo is part of the Sumida district in Tokyo, as Edo was renamed after the Meiji Restoration of 1868. The municipal authorities in Sumida are planning to devote a new museum to the world-renowned artist who spent most of his life in Edo. Some items of the collection intended for the museum will now be on view for a few weeks in Berlin. Many of the works have never been seen outside Japan.

Hokusai and Ukiyo-e (pictures of the transient world)

Hokusai’s father came from Uraga, near Edo. It was off the coast of Uraga that the American Commodore Perry was to appear with his “black ships” in July 1853, four years after Hokusai’s death, in order to put a forcible end to Japan’s isolation policy (sakoku) which had been in existence since 1635. Hokusai was temporarily adopted by his uncle, a mirror-maker at the court of the Shogun. At six he was able to draw. By the age of twelve he was working in one of the many libraries in Edo that lent out printed books. By the time he was eighteen he was already a master of the art of the woodcut. The multi-coloured woodcut had been practised in Japan since the 1740s and achieved a preliminary apogee in the 1790s, a process in which Hokusai played a major part. At that time there were some artists who would use up to 70 colour plates for a single woodcut print. Yet at the age of 22 years Hokusai was more inclined to be a draughtsman than a woodcut artist.

The Japanese paper manufacturers and publishers had wisely agreed on the production of only two paper formats (oban and chuban) – a rationalization measure that permitted high print runs at ever lower prices.

Bijin-ga, or pictures of beautiful women (Yoshiwara, the famous amusement district, was in Honjo-Sumida); pictures of Sumo wrestlers, or sumo-e, whose arenas were located in Honjo-Sumida; pictures of Kabuki actors, whose theatre was also in Honjo-Sumida – all those were ukiyo-e, pictures of the fleeting, transient (entertainment) world, which the woodcut artists produced in large numbers. Flying dealers sold them all over Japan. Most of their customers were middle class. The term ukiyo also means an impermanent world in the Buddhist sense, as Buddha also taught the transience of all things. But they also included illustrations of flowers and plants drawn with scientific precision, illustrations for novels – by about 1780 650 novels a year were being printed – or classical texts, such as the scenes from the life of Prince Genji, were part of the repertoire of a draughtsman and woodcut artist at that time. Hokusai himself produced over 1,000 illustrations for novels in that period.

A certain, albeit minor, European influence manifested itself about 1770 with the appearance on the Japanese market of the zograscope, an “optical diagonal machine” for viewing prints, which had been delighting the European public for some time. The Dutch imported the devices through Nagasaki, with the result that the Japanese artists learned to draw from a central perspective. Most of the scenes chosen by the artists to depict from a central perspective – views of Holland for example – were alien to the Japanese eye. The Japanese tradition of showing perspective was a different one and went back to much older painting traditions. The zograscope images, with their scenes taken from all areas of the then known world, gave the beholder the feeling of being at the centre of the action. It was a kind of global television for the 18th century. Hokusai also designed zograscope images and took an intense interest in the central perspective.

By about 1700 Edo already had 1.2 million inhabitants. It was a rich and freely spending public that Hokusai grew up among: merchants and samurai, daimyo (princes) and courtiers. Books could easily be published in print runs of 13,000 copies. From one wooden plate one could make many hundreds of proofs. Millions of the colour prints were sold. Hokusai was praised far and wide for the versatility of his style. Although he did not invent “Manga”, his woodcut “Hokusai Manga” is a household name even today and always available as a reprint. And yet it is “only” a painting manual that arose as a woodcut print in several volumes from 1814 onwards on the basis of about 4,000 drawings done by Hokusai himself. Looked at today, it seems like a portrayal of life in Japan, providing both a wealth of information and tremendous subtlety of design. It is said that Hokusai painted about 150 pictures, though not all have survived. Some – including a self-portrait – will be on view in Berlin.

Hokusai lived to be almost 90, and his productive period lasted well over 70 years. Even in old age he continued to be active. Towards the end of his life he would rather be seen as a painter than as a woodcut artist or draughtsman. In his epilogue to an 1834 edition of the work “One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji” he wrote: “Ever since I was six years old I have drawn things I saw about me. Since my 50th birthday I have published many works. Yet all the works I did before my 70th birthday were insignificant. It was only when I was 73 that I understood a little of the anatomy of animals and the life of plants. If I make the effort I shall have made further progress by the time I am 80, and at 90 I shall be able to uncover the final secrets. And when I am a hundred years old, the individual strokes and dots will come to life all on their own. May the god of longevity ensure that this conviction of mine does not remain an empty phrase.”

Hokusai’s reception in Europe

The response of 19th-century Europe to the work of Hokusai was overwhelming. The Dutch, with whom Hokusai could deal directly despite strict controls, brought colour woodcuts and paintings to Europe in his lifetime.

Hokusai is said to have painted forty pictures for Captain Bloemhoff, who headed the Dutch trading post in Deshima from 1817 to 1822. Franz von Siebold, a German doctor from Würzburg who worked for the Dutch on Deshima from 1823 to 1829, collected works by Hokusai, which are still to be found in several European collections today. As early as 1858 Siebold reproduced one of his works in his encyclopaedic book on Japan “Nippon – Archiv zur Beschreibung Japans ...”. This launched Hokusai’s triumphal progress in Europe and the United States. In 1862 the first exhibition of Japanese art was mounted in Paris. In 1893 Ernest Fenollosa (1853–1908) showed the first Hokusai retrospective in the West, in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. In 1901 over 600 works by Hokusai were displayed in Vienna’s Kunstgewerbemuseum. This was followed in 1913 by a major exhibition in Paris. The first biography to appear in Europe was published in 1880, to be followed in 1896 by a second in Paris, from the pen of Edmond de Goncourt. In the Paris of the day, which was the world capital of art, Hokusai and his fellow Japanese artists were all the rage. A dozen galleries were competing for buyers, representing some four dozen Japanese artists in Europe, including Harunobu, who was a bit older than Hokusai, Utamaro, his contemporary, Hiroshige and Kunisada, both much younger than Hokusai, to name only a few. Many European artists of that period succumbed to the influence of Hokusai’s work and collected his woodcuts: Degas, Gauguin, Yavlensky, Klimt, Marc, Macke, Manet (who painted Zola’s portrait against the background of a Japanese woodcut), Monet (who collected several hundred Japanese woodcuts), Mucha, Pissarro, Toulouse-Lautrec, Whistler, Valloton, van Gogh, and others. Samuel Bing (1838–1905), who had opened a gallery called “L’Art Nouveau” in Paris in 1895, thus giving the new style its name (although as it spread across Europe it assumed other names as well), began as a dealer in Japanese art. Between 1860 and 1920 Japanese art enjoyed a great vogue all over Europe and the United States. Hokusai, however, did not live to see the success of his art in Europe.

The historical background: The development of the city of Edo since 1600

Shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu, who ruled from 1603 to 1605, succeeded in pacifying Japan after a long civil war in which Europeans participated. He established his seat of government in Edo, now Tokyo, far from the ancient city of Kyoto, where the Japanese emperor resided in relative impotence. One could call the system of rule instigated by the Tokugawa clan a military dictatorship, with the Shogun as field marshal. The Shogun, influenced by a strict interpretation of Confucianism, had instituted a rigid social hierarchy: at the apex was the military caste of samurai swordsmen. Then came the peasants and craftsmen, and at the bottom of the social pyramid were the merchants. The latter, however, were not prevented from getting very rich. This enabled them later, in view of the government’s chronic shortage of cash, to buy the right to bear swords. In 1639 the Portuguese and Spaniards, as representatives of the European Catholic powers, were expelled by Tokugawa Iemitsu from the country they had first reached some 90 years earlier. Japan did not want to share the fate of the Spanish colony known as the “Philippines”. Only the Dutch Protestants, who had been active in Japan since 1600 and had much to report about the European Catholic powers, were allowed to maintain a trading post on the little island of Deshima in Nagasaki harbour, 1,300 kilometres away from Edo. For the Japanese Deshima was a window on Europe. Every four years the head of the Dutch trading post had to make the journey to Edo and report to the Shogun on current developments in Europe, particularly in the scientific field. On a neighbouring island the Japanese had set up a second “window”, where Chinese merchants could settle and engage in commerce. Otherwise Japan was cut off from the world until 1853, and an “eternal peace” prevailed. For over 250 years, up until the Meiji Restoration of 1868, the Tokugawa clan would rule the land with an iron fist.

The fact that Edo became the world’s largest city at that time was due to a precautionary measure taken by the Shogun Iemitsu around 1635. As he mistrusted the country’s princes (daimyo), of whom there were over 200, he forced them to maintain a residence in Edo. The families, especially the womenfolk and eldest sons, were compelled to live in Edo as hostages, even when their daimyo was in his home province. Every two years each daimyo had to travel to Edo, hand over expensive gifts and report to the Shogun. The costs this entailed were so great that some were soon reduced to poverty.

For Edo, however, and its urban development the system of compulsory residence acted as a great economic stimulus. Artists from all over Japan flocked to the capital to decorate the palaces, to illustrate books, to paint. As a result Edo became not only the economic, but also the artistic centre of the country.

The rank of a daimyo was measured by the amount of rice he could harvest in his province. One of the richest is said to have harvested 5 million bushels of rice. Many of the daimyo, in turn, wanted to turn their rice into cash, as paying for everything with sacks of rice was not very convenient. This gave the merchants of Edo their chance. They paid in silver coins for the rice which they stored in large warehouses on the river Sumida, where today’s Sumida district lies. And they grew very rich.

In this dockside area on the river Sumida lived the artist Hokusai, surrounded by rich rice merchants, traders and burghers, who could afford to pay for art, books and poems. In the 1790s, when Hokusai was about thirty, the literacy rate is supposed to have been about 70% for men, and about 50% for women. In 1808 Edo had 600 lending libraries. Books appeared in print runs that were large for the time. Edo was a city full of readers and connoisseurs of illustrated books, colour woodcuts and paintings. In Hokusai’s time Edo, a lively metropolis of over a million people, was a paradise for artists.

Press office:

artpress - Ute Weingarten

Tel +49 30 25486-236 Fax +49 30 25486-235 E-mail presse@gropiusbau.de

Image: The Great Wave off the Coast of Kanagawa

From the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji

Date of origin: c. 1831 | Period: Iitsu

Press Conference Thursday 25 August s011 h 11a.m.

Martin Gropius Bau

Niederkirchnerstrasse 7 - Berlin

Opening Hours: Wednesday to Monday 10-20

Tuesday closed