Maelee Lee and Aldo Tambellini

dal 5/10/2011 al 4/11/2011

Segnalato da

5/10/2011

Maelee Lee and Aldo Tambellini

Chelsea Art Museum, New York

From the perspective of artist Maelee Lee, her photographic installations are a manifestation of atmosphere, negative space, as well as artistic or infinite space. Black Zero is a major retrospective exhibition of paintings, sculpture, lumagrams, videograms, film, video, and television work by the American avant-garde artist, Aldo Tambellini.

Maelee Lee - Infinite Space

curated by Dr. Thalia Vrachopoulos, Ph.D and Elga Wimmer

From the perspective of artist Maelee Lee, her photographic installations are a

manifestation of atmosphere, negative space, as well as artistic or infinite space.

These concepts, or morphologies, closely challenge how we understand “space,” which

can take on different forms depending on one’s approach: through mathematics,

psychology, mechanics, philosophy, and that of one’s personal history.

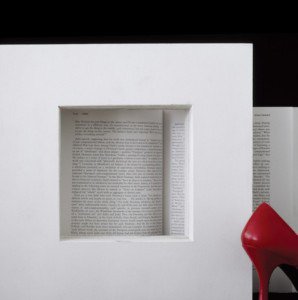

In her first series, entitled Absolute Space (2011), Lee tackles issues of time and

space, being and existence. Her references to the real, physical world take on the

form of everything from a mountain or the sea to pages of a book. Within Lee’s

worlds, white sculptural, geometric forms are multiplied through planes in space and

time, as if they have been refracted and reflected through infinite mirrors. At the

same time, the curves of a woman’s high heel shoe contrasts with its pristine,

linear surroundings, and act as a distinct and direct allusion to a female presence.

The spatial relationship between these disparate elements and its position in

respect to the viewer makes us further question the work’s deeper, ambiguous

meanings.

Lee’s 2010 Ocean series are photographs that present contradictory conceptions about

space: one that is solid and visible, while alternately can be observed and

invisible. The solid/void relationship holds great significance for Korean culture,

and is associated with the yin and yang, or feminine and masculine principles of

Taoism. In this context, the void is full and empty simultaneously. In Lee’s hands,

this idea is translated into physically sliced photographs of the ocean taken during

different weather conditions so that the horizontal slats are read as solid and

voids. Much like Carl Andre and Sol LeWitt’s Minimalist sculptures are intended to

reduce artistic components to their most basic levels, Lee appropriates these

minimal, clean lines that further emphasize the conceptual above all else.

Lee’s Poetics of Space (2011) take on socio-political ideals of feminist thought

through a

photographic series depicting land-seascapes with underlying textual references. To

Lee, substance is represented by natural forms while the texts refer to immaterial

concepts and worlds of a wholly different time and space. For instance, when Lee

alludes to Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own, her intention is to encompass the

author’s own historical and personal environment. In the essay, Woolf postulates for

women’s right to have a space of their own in which to be creative and the means

with which to support themselves. Lee pairs imagery taken from the concrete, visible

world and the immaterial concept of liberation, and in this way presents both

solidity and the intangible. Lee also employs text from Heo Nanseiolheon, a Korean

poet of the 16th Century Chosun Dynasty. In Kyunwonka, Heo’s stance is decidedly

feminist and writes about the unrequited longing of women for such recognition.

Woolf’s writings, just as with those of Heo, advocate for women’s independence.

Although these two heroines

didn’t live to see their independence during their own lifetimes, Lee celebrates

these authors as being far ahead of their own time and space. By inscribing these

landscapes with their words, Lee claims these spaces and rights on behalf of them.

Taken as a whole, Lee’s work examines a myriad of themes from ancient Greek geometry

to Asian philosophy and modern philosophical precepts of space as they pertain to

feminist thought. In this way, her work cannot be easily categorized and must be

viewed on multiple levels. However, her work is ultimately deeply rooted in

conceptual ideals that merge history, personal experience, and our perceptions of

reality.

Chelsea Art Museum, home of the Miotte Foundation, presents contemporary thematic

exhibitions that foster critical thinking about today's world. CAM strives to

cultivate respect for the world at large, exhibiting seminal, but relatively

unexplored dimensions of 20th and 21st century art, particularly focusing on

international artists that have less exposure in the United States. The museum is

founded on the legacy of abstract expressionist painter, Jean Miotte, whose

foundation is housed within the museum.

-----

Aldo Tambellini - Black Zero

The Boris Lurie Art Foundation is pleased to announce a major retrospective exhibition of paintings, sculpture, lumagrams, videograms, film, video, and television work (1960-1990) by the American avant-garde artist, Aldo Tambellini, entitled Black Zero.

Born in Syracuse NY in 1930, Tambellini was brought to Lucca, Italy at the age of eighteen months by his soon to be separated parents and would live there through the Second World War, the experience of which – his town was mercilessly bombed by the Allies, and he saw death and destruction at intimate range – would mark his soul and his art indelibly. Demonstrating a precocious talent and a passion for art, he was enrolled in a full-time art academy at the age of ten. After his return to the United States in 1945 he entered a public vocational school, upon graduation from which he was awarded a full scholarship to study art at Syracuse University whence he would go on to take a masters degree at Notre Dame University under the tutelage of the renowned sculptor Ivan Mestrovic.

Tambellini came to NY in 1959, living in a storefront in the East Village, from which he would mount site installations, exhibit large-scale sculpture and project proto-new media events onto the walls of neighborhood buildings. He worked closely with a number of African American writers and artists, particularly the writers associated with the politically charged literary journal, UMBRA, and with whom he felt a special affinity, being that it had been an American Buffalo Regiment that liberated the town of Lucca at the end of the war.

His work, even at its most abstract, has always been informed by a powerful political awareness and resistance against injustice. With the early underground art collective, Group Center, of which he was a founder, he mounted art actions that would prefigure both the social activism of the later sixties and the guerilla art actions of subsequent avant-gardes. Group Center’s vision of a new art of global creative communities prefigures the integrative social concepts that animate much of the most advanced and radical art of our own time. Like Boris Lurie’s No!Art Movement, Group Center actively resisted the cynical, commercialist, self-serving, and, ultimately, vapid corporate art that would captivate the masses, including the art-collecting masses and museums, for decades. Group Center’s The Event of the Screw (1962) was a direct confrontation with the art hierarchy of the day akin to the famous open letter to the Metropolitan Museum from The Irascibles in 1950.

Although Tambellini’s reputation as a new media pioneer has grown impressively in recent years throughout the performance and avant-garde film communities in America and abroad, with widespread acknowledgement of his early and important contributions to modes of art that had no name when he was creating paths among them, much of even his new media work is infused with a profound sense of the painterly that developed during a lifetime of collateral work in two-dimensions. The present exhibition includes a broad sampling of his painting and related work over a period of more than three decades, covering the essential course of his long-standing and obsessive engagement with Black, which for him is, simply, the source and destination of everything; it is a spiritual and cosmic – and cosmogonic – principle akin to fire for Heraclitus. Over the decades of his work in black, Tambellini has evolved from the distressed, even pessimistic, observer of the destruction of the human and natural worlds to a philosopher looking to distant, and inner, space with equanimity, and even hope. His Destruction Series of the early sixties places him alongside the early Yves Klein and the mature Alberto Burri, and certainly in a conceptual and tactical lineage with Lucio Fontana. His penetration of the pictorial plane and virtual attack upon it with gouges, drill-bits and flame bespeak the fury of this witness of humanity at its worst against the habits and limits that cast it back ceaselessly into its brutal past. Astonishingly, in his later body of distressed-surface works (1988-1989), he creates a sense of boundless possibility and hope using more or less the same tactics, materials, and iconography as he had in the earlier series, testimony to a long life devoted to the struggle of understanding.

To some extent, Tambellini’s majestic paintings might actually be viewed as preparatory studies for the time-based media and conceptual works he had already begun creating in the early sixties. His film, performance, and new media work have inspired several generations of the new breed of artist, the “primitives of a new era,” as Tambellini has called them, including, early on, Timothy Leary, whose notion of a neurological art (and eventually, the “light show” that became so widespread throughout the psychedelic era) can be traced back to Tambellini’s light projections of the early/mid sixties, and Andy Warhol, whose own Exploding Plastic Inevitable is more and more widely acknowledged to owe a significant debt to Tambellini’s Black Zero. As the founder and proprietor of the Gate Theater at Tenth Street and 2nd Avenue (1966-1969), the only cinema in NY (and possibly anywhere else) showing continuous avant-garde film every day of the week, Tambellini was among the guiding spirits of the most advanced garde in the American art of its day. And when he and colleague Otto Piene (of the Zero Group) opened the Black Gate performance, installation, and experimental space for artists in 1967 on the floor above the cinema, Tambellini’s position within and his gift to the art world of his day took on revolutionary proportions.

Tambellini’s own films, including the landmark Black Film Series, which was among the first works to treat film as the venue for a total sensory experience, are justly regarded as masterworks of the experimental or underground genre. He is generally credited with having, along with Otto Piene, created the first work of art for television (Black Gate Cologne, which aired in Germany in 1968). Tambellini was also part of WGBH’s The Medium is the Medium, which aired in Boston in 1969 and marked the first time in history that American artists took over the airwaves of television and broadcast art. When Piene became director of the renowned Center for Advanced Visual Studies at MIT, he invited Tambellini to become a fellow, and from 1977-1984, Tambellini would create works and events that seem, in retrospect, to have prefigured not only the orientation of the new media art of the last decades, but larger social trends, such as social networking and communications-based mass actions as well.

More recently, Tambellini’s attentions have been devoted to poetry and to explicitly political art, though he has also continued to sketch larger-scale projects in various media, most of which have remained unrealized due to health considerations.

In his long career, he has worked alongside of and given a forum to artists such as Nam June Paik, Charlotte Moorman, Yoko Ono, Hans Haacke, Ad Reinhardt, Julian Beck and Judith Malina, Yayoi Kusama, Boris Lurie, Otto Piene, Carolee Schneemann, Jonas Mekas, Louise Bourgoise, Irene Rice Periera, Stan Brakhage, Jack Smith, Cecil McBee (and other radical jazz artists), Ishmael Reed, Bob Downey, and Brian De Palma, but until recently he had not shown his two-dimensional work in almost 40 years. The present exhibition represents the first truly large-scale, and the first ever museum show of his work in all its aspects, though exhibitions of portions of his opus have already been tentatively scheduled by the Pompidou and the Tate Modern for 2012. The Herter Gallery of the University of Massachusetts, Amherst will present a significant show in November 2011.

Like Boris Lurie, Tambellini’s dear friend for almost fifty years and under the aegis of whose Art Foundation the present exhibition has been mounted, Aldo Tambellini was among the revolutionary artists of the long-submerged American avant-garde of the fifties and sixties who struggled against the complacency and oblivion that characterized the nascent international superpower and the false values that its art market and the manipulators of that market foisted upon an unwitting public.

The Boris Lurie Art Foundation is a non-profit organization dedicated to art education, the encouragement and support of politically and socially engaged art, especially work that has been neglected by the art mainstream on account of its radical content, and to the propagation of knowledge of the art of Boris Lurie himself. It was with a generous gift from the Lurie Foundation that much of the art in the present exhibition has been salvaged from a storage facility where it had lain forgotten for three decades and restored to its present condition.

A fully-illustrated catalogue, including essays by Paolo Emilio Antognoli Viti, Marek Bartelek, Lisa Paul Streitfeld and Joseph Ketner will be available during the run of the show. The performance of Black Zero, curated by Chistoph Draeger, has been subsidized by a generous grant from the Swiss Arts Council, Pro Helvetia.

Image: Maelee Lee, Absolute Space R-01, 2011. C-type Jet Print, Saitec. 47 x 47 inches.

For more information please contact:

Chris Longfellow Press Officer The Chelsea Art Museum 212-255-0719 x 108 press@chelseaartmuseum.org

Press Preview: Thursday, October 6th, 4pm – 6pm

Opening Reception: Thursday, October 6th, 6pm – 8pm

Exhibition: Thursday, October 6th – Saturday, November 5th, 2011

Chelsea Art Museum

556 West 22nd Street | New York, NY 10011

212.255.0719 ~ chelseaartmuseum.org

Museum hours: Tuesday – Saturday: 10am – 6pm; Thursday: 10am – 8pm; closed Sunday

and Monday

General admission: $8 for adults; $4 Students and Seniors

Directions: C/E trains to 23rd Street and 8th Avenue