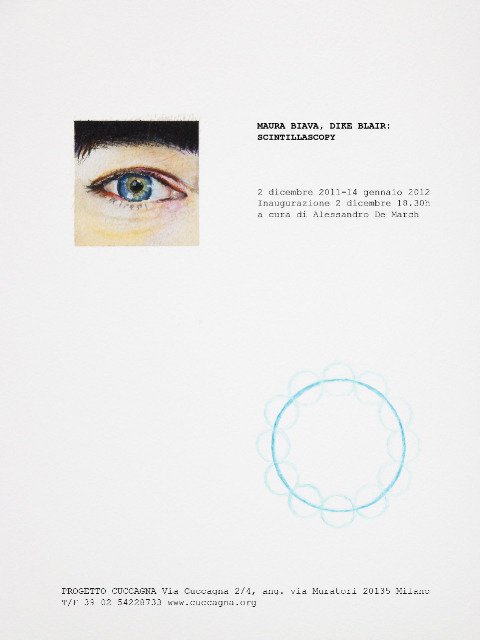

Maura Biava e Dike Blair

dal 1/12/2011 al 13/12/2011

Segnalato da

1/12/2011

Maura Biava e Dike Blair

Cascina Cuccagna, Milano

Scintillascopy. Biava abbina due o piu' formule matematiche per creare una nuova forma tridimensionale, che riflette anche una combinazione linguistica. Blake dipinge occhi di donne e finestre, 'filtri' tra il mondo interiore e quello esteriore.

---english below

a cura di Alessandro De March

Nel cuore del centro cittadino, nascosta tra i palazzi di Corso Lodi, alle spalle di Porta

Romana, si trova una delle più antiche cascine agricole milanesi: la Cascina Cuccagna,

a Milano dal 1695.

Per strapparla dall'abbandono, un consorzio di otto associazioni milanesi ha elaborato

un progetto che vede la sua trasformazione in un nuovo spazio pubblico: "un centro

polifunzionale d'iniziativa e partecipazione territoriale".

Progetto Cuccagna è finalizzato all'emersione dal basso e dall'interno del territorio

dell'eccellenza artistica, culturale, artigianale e tecnologica. Esso contribuisce alla

costruzione di una identità culturale del territorio urbano fondata sulla consapevolezza

delle sue nuove complessità.

Di seguito riportiamo uno stralcio del dialogo tra i due artisti protagonisti del progetto:

Maura Biava e Dike Blair, entrambi presenti all’inaugurazione della mostra.

Maura Biava: Perché dipinge gli occhi delle donne?

Dike Blair: L’occhio è ricco di metafore, in modo particolare se considerato dal punto di

vista dell’arte e del guardare, per cui è naturale che da sempre moltissimi artisti abbiano

scelto di dipingere gli occhi nelle loro opere. Uno degli aspetti più misteriosi e

affascinanti dell’occhio è la sua funzione di “filtro” tra il mondo interiore e quello

esteriore. Un altro soggetto che amo dipingere sono le finestre, la cui funzione è

assimilabile a quella degli occhi. Osservare gli occhi e cercare di penetrarne i segreti è

una delle interazioni più complesse, e a volte piacevoli, che possiamo sperimentare. Il

fatto che i soggetti delle mie opere siano donne ha sicuramente a che fare con il piacere

nella sua accezione erotica.

DB: Mi può descrivere il metodo che usa? So che lei inizia numerosi progetti

sintetizzando una formula matematica e dando ai risultati un nome evocativo e poetico.

Ritengo che il suo metodo si possa descrivere come poesia scientifica o scienza

poetica.

MB: Considero la matematica alla stessa stregua di un linguaggio, un linguaggio in

grado di informare e dare forma, difatti molte formule matematiche possono essere

convertite in rappresentazioni grafiche di tipo geometrico. Queste rappresentazioni

geometriche sono alle volte presenti nella produzione artistica dei secoli passati per

descrivere nozioni o idee universalmente condivise sul mondo. Ad esempio, Dio crea un

cerchio, con o senza compasso, e quel cerchio rappresenta la terra appena creata.

Ecco perché io posso utilizzare la formula e darle un nome: cerchio = creazione.

Quando abbino due o piu' formule matematiche per creare una nuova forma

tridimensionale, la nuova forma riflette anche la combinazione linguistica. Una delle

opere esposte, ad esempio, si intitola 'In search of sinchronyc creation' 'Alla ricerca

della creazione sincronica ' .

DB: Per la nostra mostra ha portato il cibo in tavola. Ce ne parla?

MB: Si tratta fondamentalmente di pasta. Ho iniziato a guardare la pasta con occhi

diversi quando frequentavamo l’American Academy di Roma. All’Accademia c’erano

numerosi borsisti di origine italiana, le cui famiglie vivevano negli Stati Uniti da

generazioni, eppure loro si consideravano italoamericani, e nutrivano un profondo

legame con la cultura italiana. Sono cresciuti sentendo raccontare le storie del loro

paese di origine e sentono nostalgia dell’Italia, di cui subiscono il fascino. Anche se

negli ultimi 15 anni ho vissuto ad Amsterdam, sono italiana e avevo sempre pensato alla

pasta come ad una sorta di cliché sull’Italia; invece ho compreso che per gli italiani nati

e vissuti all’estero la pasta può avere connotazioni molto personali e profonde, ad

esempio può dare corpo ad una fantasia ed evocare vecchie storie e messaggi

subliminali. Così le forme della pasta si sono trasformate per me da cliché a simboli. Per

la nostra mostra ho voluto “decostruire” le diverse forme di pasta elaborando le formule

matematiche che le generano. Con questo metodo riesco a scoprire i lori nomi reconditi.

DB: In questo caso ha invertito la sua metodologia abituale?

MB: Proprio così. E lei? Lʼesperienza dellʼAccademia che influenza ha sulla sua arte?

DB: Desideravo creare opere che riflettessero la mia esperienza in terra italiana, ma

senza “concepirle”: volevo infatti che nascessero spontaneamente. È stato un processo

molto lungo, ma un giorno, mentre stavo osservando un dettaglio di una fotografia che

avevo scattato al ritratto di Luca Pacioli dipinto da Jacopo de Barbari, conservato a

Napoli nel Museo di Capodimonte, ho capito che buona parte del tempo trascorso a

Roma senza creare lo avevo passato ammirando gli antichi capolavori artistici e quindi

perché non mettere a frutto tutto questo? Ho compreso inoltre che cosa rappresenta per

l’identità italiana questo patrimonio artistico, come sia integrato nel DNA della nazione, a

prescindere dal grado di consapevolezza degli italiani di oggi. Nel dipinto erano

rappresentati vetro, riflessi e finestre, tutti soggetti che amo dipingere. Per la nostra

mostra ho preparato un dettaglio di una Santa Lucia del Guercino conservata a Villa

Aurora a Roma. Inutile dire che adoro gli occhi della santa nella fondina.

MB: Ritengo che quell’opera sia fondamentale nella nostra mostra perché affronta

apertamente il concetto di visione. Anche se l’immagine che ha ispirato il suo lavoro

risale all’inizio del diciassettesimo secolo e costituisce un classico esempio di

iconografia tradizionale, sembra un’opera quasi surrealistica. Le mie opere spingono

spesso chi le osserva a riconsiderare la loro percezione della realtà, così come le sue

del resto. Ho risposto alla sua Santa Lucia con opere che raffigurano piatti e occhi,

spero che le piaceranno.

---english

curated by Alessandro De March

In the city center of Milan there is one of the most ancient, beautiful and old farm: the

Cascina Cuccagna, built in the XVII century.

To save it from neglect and speculation a consortium of eight associations has

conceived a project focused to the artistic, cultural and technological excellence; it

contributes to the construction of a new cultural identity on the urban territory founded on

the awareness of its new contemporary complexity.

Following is a dialogue between the two artists invited for the first time to the Cuccagna

project, Dike Blair and Maura Biava.

Maura Biava: Why do you paint women's eyes?

Dike Blair: The eye is metaphorically rich; especially when it comes to the subject of

art and seeing, and thus it’s no surprise that the eye has been a subject for many artists

for a long time. One of the mysterious and fascinating things about the eye is how it’s the

membrane between inside and outside. I also like painting windows, which function in a

similar way. Looking at and into eyes is one of the most complicated, and occasionally

pleasurable, things we do. And the fact that my subjects are female certainly has to do

with erotic pleasure.

DB: Can you tell me about your methodology? As I understand it, you begin many

projects by synthesizing a mathematical formula and poetic "naming." I think of your

method as scientific poetry or poetic science.

MB: I see mathematics as a language; one that can inform shape, many formulas can

be converted to graphic geometric representations. These geometric representations

often appear in historical art in connection with generally shared notions or ideas about

the world. For example, God creates a circle, with or without a compass, and that circle

is the newly created earth. And that's why I can work with the formula and name it, circle

= creation. When I combine two mathematical formulas to create a new three-

dimensional shape, that new shape also reflects the linguistic combination. One of the

works in the show, for example, is titled, In search of sinchronyc creation.

DB: For our show, you've brought food to the table. Can you talk about that?

MB: It's mainly pastas. I started to see pasta differently when we where in residency

at the American Academy in Rome. There were fellows at the Academy of Italian

descent, whose families have lived in the US for generations, yet they consider

themselves Italo-American, and feel a deep connection to Italian culture. They’ve grown

hearing stories of their country of origin and feel the pull of and a longing for Italy. While

I’ve lived in Amsterdam for the last 15 years, I’m Italian and I’d always thought of pasta

as some sort of Italian cliché; but I came to realize that for non-native Italians, pasta can

represent something very personal and deep...it can embody a kind of fantasy and

evoke old stories and subliminal messages. So pasta shapes changed from being

clichés into symbols. For our show I’ve been “deconstructing” the various shapes of

pasta, finding the mathematical formulas that generate those shapes. This way I'm able

to find their 'hidden' names.

DB: So youʼve inverted your normal methodology?

MB: Exactly. What about you? Did your time at the Academy have an impact on what

you do?

DB: I wanted to make things that reflected my time in Italy, but I didn’t want to

“conceive” them, I wanted them to arise naturally. It took a very long time, but finally, as I

was looking at a photographic detail I’d taken of Jacopo de Barbari’s portrait of Luca

Pacioli that hangs in Naples at the Capodimonte. I realized that much of my non-studio

time in Rome was spent contemplating old art and why not make work about that. And I

realized how central this art is to Italian identity, how much it’s the bones of the country,

whether or not contemporary Italians give it a second thought. Now, the painting pictured

glass, reflections and windows, all things that I love to paint. For our show, I painted a

detail of a St. Lucy by Guercino, that’s in the Villa Aurora in Rome. Perhaps this is

needless to say, but I love the eyes in her bowl.

MB: I think that work plays a key role in our show because directly addresses the

notion of vision. Even if the image that inspired you is from the early seventeenth-

century, and it’s iconographically traditional, it seems an almost surrealistic painting. I

think that my work often asks viewers to consider their perception of reality; and I think

yours does as well. I’ve responded to your St. Lucy with a couple works that involve

plates with eyes...I hope you like them.

Opening 2 Dicembre 2011, h. 18.00

Cascina Cuccagna - Primo Piano

via Cuccagna 2/4, ang. via Muratori - 20135 Milano

da lunedì a venerdì, dalle 14.30 alle 18.30