4/11/2011

Francesca Woodman

SFMoMA, San Francisco

Approximately 160 vintage photographs -many that have never been on view before- drawn primarily from the Woodman family's personal collection and made available solely for this project. The exhibition also affords the fullest view of Woodman's oeuvre to date, contextualizing her most canonical pictures as part of a larger body of work that is more varied than previously suspected.

curated by Corey Keller

Francesca Woodman, the most comprehensive exhibition to date of Woodman's brief but extraordinary career, will premiere at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) on November 5, 2011, through February 20, 2012.

In less than a decade, before Woodman committed suicide in 1981 at age 22, she produced a potent body of photographs exploring the human body in architectural space and the complex problem of representing the self. Haunting and intimate, direct and visceral, her work reveals the unusually coherent vision of an artist who had barely entered adulthood but who has greatly influenced subsequent generations of artists, particularly women.

Now, 30 years after her death, the moment is apt for a historical reconsideration of her work and its initial reception. Organized by SFMOMA Associate Curator of Photography Corey Keller, Francesca Woodman continues the museum's leading scholarship in photography by assembling approximately 160 vintage photographs—many that have never been on view before—drawn primarily from the Woodman family's personal collection and made available solely for this project.

These mostly black-and-white pictures, which are frequently inscribed with text by Woodman, offer an occasion to appreciate the artist's own rarely seen vintage prints and to experience them as both objects and images. The exhibition also affords the fullest view of Woodman's oeuvre to date, contextualizing her most canonical pictures as part of a larger body of work that is more varied than previously suspected.

According to Keller, "The intersections of Woodman's work with feminist theory, Conceptual art, and photography's relationship to both literature and performance are the hallmarks of the fertile moment in American photography during which she came of age—a time when schools were no longer producing commercial photographers but nurturing artists. Photography was also blossoming in museums and the market as well, producing a wildly diverse set of photographic practices. This exhibition examines the expression of a highly subjective artistic vision. It also presents a timely opportunity to reconsider Woodman's work within this critical juncture in American photographic history."

Spanning the artist's career, Francesca Woodman will examine not only her earliest student experiments at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) but also her late, large-scale blueprint studies of caryatid-like figures for the Temple project as well as her fashion photography—both of which are much less discussed than her student work and suggest a trajectory her career might have followed had it not been cut short. Woodman also experimented with moving images, and the exhibition will include in-gallery screenings of her recently discovered and rarely seen short videos. The presentation is rounded out with a selection of artist books.

A definitive catalogue, benefiting from new research and previously unpublished photographs, accompanies the retrospective and features new essays by Keller, Julia Bryan-Wilson, and Jennifer Blessing. Following its debut at SFMOMA, the exhibition will travel to the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York in spring 2012.

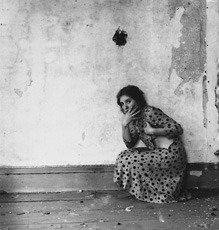

Woodman used her own body as her primary subject, relentlessly exploring and, in the process, complicating the genre of self-portraiture. Her figure—most often shown nude in the dilapidated, gothic-like interiors she was drawn to (and sometimes lived in)—shifts back and forth between appearance and disappearance, sexuality and innocence. In some works her body appears blurred in motion or enveloped in peeling wallpaper. In others, it is pressed against mirrors or into furniture, posed alongside symbolic objects such as an eel and dead birds, or juxtaposed against the textures of fur or ragged cloth. The work frequently evokes the surrealist writings and Victorian-era fiction the artist adored.

The first major exhibition of Woodman's work took place in 1986, five years after the artist's death, at the Wellesley College Museum and traveled to a number of university museums in the United States, including Hunter College in New York. Although Woodman had participated in a few group exhibitions during her lifetime, her work was at that time largely unknown, even within the photography community. The prestige of a solo traveling exhibition, coupled with a slim but scholarly catalogue (with essays by noted art historians Rosalind Krauss and Abigail Solomon-Godeau), had the effect of posthumously catapulting Woodman to a level of attention not usually experienced by an artist so young and obscure.

"Woodman's age has been used as ballast for claims of prodigy and as fodder for claims of insignificance," Keller states. She argues, however, that the work must be appreciated on its own terms. "The work's youthfulness, its sense of being on the cusp, is also the source of its potency. Although Woodman was unusually talented and precocious, her compact career represents an artist on the verge, neither mature woman nor innocent child but in that fertile, tumultuous, provisional moment before true maturity. Her art is inward looking, experimental, and incomplete."

Woodman grew up surrounded by art and artists. The daughter of ceramicist Betty Woodman and painter George Woodman, she was born in 1958 and raised primarily in Boulder, Colorado, where her parents were on the fine arts faculty of the University of Colorado. From an early age Francesca and her elder brother, Charlie (now a professor of electronic arts and a practicing artist), clearly understood the intensely disciplined working habits that being an artist required.

She first experimented with drawing, but when she began photographing around the age of thirteen with a camera given to her by her father, she showed an immediate and sophisticated awareness of the problems and opportunities of the medium. By the time she enrolled as an undergraduate at RISD in 1975, she already had a focused approach to her work.

At RISD, Woodman developed what would become a signature approach to her work, taking subjects (or class assignments) and developing them into extended serial explorations. She likened her process to that of a musical composer, developing increasingly elaborate variations on themes. In her early series Spring in Providence (1976)—one of the few that can be read in a logical order with a clear narrative arc—she presents a sequence of four frames in which she cuts holes in a roll of backdrop paper, revealing cabbages that peek through the paper like spring blossoms emerging from snow. But her series were often less straightforward or sequential: she returned repeatedly to a subject or a particular location, over and over again, each time from a new angle.

Woodman's House series (1975–78) was made in an abandoned house in Providence, where she intervened into the architecture by arranging doors and mantelpieces at precarious angles. Nude or clad in vintage dresses, Woodman moves through the dilapidated space, her body appearing to meld into the house itself. She similarly explored the relationship of the body to space in a series of pictures in RISD's Waterman Building; the rooms full of props for drawing classes (including glass boxes for practicing rendering transparent and reflective surfaces) and the natural sciences lab, with its cases of taxidermy animals and scientific specimens, provided ready-made environments for her performances.

Woodman also experimented with the limits of the photographic medium, pushing its relationship to time and the visible world, which crystallized in her studies of angels such as On Being an Angel (1975–78). (The theme would reemerge strongly in later series made during her junior year abroad in Rome.) The motion-blurred figures the artist has described as "ghost pictures" evoke her gothic sensibility as well as the spirit photographs made in the 19th and early 20th centuries that sought to provide photographic proof of life after death.

Following two years at RISD, Woodman elected to spend her junior year in Rome as part of the school's European Honors Program at the Palazzo Cenci. It was a transformative period for the artist. She had spent a good part of her childhood in the Italian countryside outside Florence and therefore quickly integrated into a group of young artists affiliated with the gallery and secondhand bookstore Libreria Maldoror. She found in Rome an intimate group of artistic cohorts and was the sole photographer (and only American) included in an exhibition of five young artists at the Ugo Ferranti Gallery during her stay.

After Rome, Woodman returned to RISD for one final semester and graduated early in 1978. During this final period at school and then immediately following graduation while she lived in New York, she began making more markedly experimental pictures that have been less fully considered than the body of work made during her time at RISD and in Rome. Although she continued to make gelatin silver prints, around 1980 she began exploring the diazotype process, a technique most often used for the production of architectural blueprints. She exposed large sheets of light-sensitive paper by using negatives constructed from transparent tissue paper and acetate or by projecting imagery with a slide projector.

The seeds of these experiments can be seen in Woodman's final project at RISD, her undergraduate thesis exhibition, titled Swan Song (1978). The exhibition was conceived as a full-room installation, juxtaposing large-scale gelatin silver prints (at three by three feet, the largest she had ever made) with smaller, postcard-size pictures. Even more crucial was her decided break with traditional conventions of framing and hanging. The large prints were pinned to the walls at dramatically varying heights—close to the ceiling, abutting the baseboards—and in such a manner that they deliberately engaged and activated the architecture of the room.

Woodman's experiments with diazotypes culminated in her monumental Temple project (1980). The work, which stands some fifteen feet tall, is a collage of individual blueprints, each comprising an architectural fragment. Three of the larger-than-life-size caryatid-like figures used to evoke the façade of an ancient Greek temple are on view in SFMOMA's presentation.

She also made studied attempts at commercial fashion photography during this time, hoping that it might allow her to earn a living while pursuing her art practice. Given her lifelong interest in clothes and costume, these early investigations often blur indistinguishably into her personal photography. Despite numerous attempts, she achieved little traction in the fashion industry.

In July of 1980, Woodman held an artist residency at The MacDowell Colony in Peterborough, New Hampshire. Although in some of her very earliest work Woodman had posed nude outside, evoking a seemingly traditional alignment of the feminine and the natural, the vast majority of her pictures were made inside. At MacDowell, she resumed posing outdoors. Several pictures from these series show her wrapped in long curls of shed bark, which recall her earlier RISD pictures in which her body appeared engulfed by peeling wallpaper.

Woodman's late blueprints (1980)—complex, multipart works—combine older photographs with historical imagery found in books, which she rephotographed specifically for these projects. Unlike the individual, inwardly oriented pictures that she had made earlier, the blueprints seem to represent a new avenue of inquiry, one that is less about self as subject than artist as producer.

"Woodman's pictures are ambiguous and mysterious, and as a result have ably served a variety of critical agendas and historical moments. That they remain compelling to a contemporary audience is testimony to the enduring power of the work," says Keller. "Ultimately, we are left with a deeply personal body of work imbued with a palpable sense of urgency, the efforts of a young woman only beginning to explore the endless possibilities of the photographic medium and her imagination."

On January 19, 1981, Woodman committed suicide in New York.

Authoritative Catalogue

To accompany the exhibition, SFMOMA, in association with Distributed Arts Publishing (D.A.P.), will publish a fully illustrated exhibition catalogue (cloth, 244 pages, $49.95), featuring previously unpublished images and original essays by Corey Keller, exhibition curator; Jennifer Blessing, curator of photography at the Guggenheim Museum; and Julia Bryan-Wilson, director of the Ph.D. Program in Visual Studies and associate professor of art history at the University of California, Irvine. In her opening essay Keller contextualizes Woodman's photography within the emergence of a new photographic avant-garde in the 1970s and offers a compelling argument for why a consideration of her work is urgent today. Julia Bryan-Wilson draws on her expertise in feminist art and performance art to put Woodman and her initial reception by feminist scholars—in particular, Abigail Solomon-Godeau and Rosalind Krauss—in perspective. Finally, Woodman made a handful of videos that have only recently been rediscovered; Guggenheim curator Jennifer Blessing will examine these moving-image works and their relationship to her still photography.

Related Exhibition at SFMOMA

To provide visual and historical context for Woodman's work, the presentation at SFMOMA will be accompanied by a separate but related exhibition of 1970s photography from the museum's own collection, including works by Robert Cumming, Duane Michals, and Jan Groover, among others.

Image: Polka Dots, Providence, Rhode Island, 1976; gelatin silver print; courtesy George and Betty Woodman; © George and Betty Woodman

Francesca Woodman is organized by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Major support for the exhibition is provided by The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts. Generous support is provided by the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation.

Media Contacts

Robyn Wise, 415.357.4172, rwise@sfmoma.org

Libby Garrison, 415.357.4177, lgarrison@sfmoma.org

Peter Denny, 415.357.4170, pdenny@sfmoma.org

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

151 Third Street San Francisco, CA 94103

Museum hours: Open daily (except Wednesdays): 11 a.m. to 5:45 p.m.; open late Thursdays, until 8:45 p.m. Summer hours (Memorial Day to Labor Day): Open at 10 a.m. Closed Wednesdays and the following public holidays: New Year's Day, Fourth of July, Thanksgiving, Christmas. The Museum is open the Wednesday between Christmas and New Year's Day.

Admission prices: adults: $18; seniors: $12; students: $11; SFMOMA members and children 12 and under: free. Admission is free the first Tuesday of each month and half-price on Thursdays after 6 p.m.