Hyperrealism 1967-2012

dal 21/3/2013 al 8/6/2013

Segnalato da

Museo Thyssen‐Bornemisza - Press Office

21/3/2013

Hyperrealism 1967-2012

Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

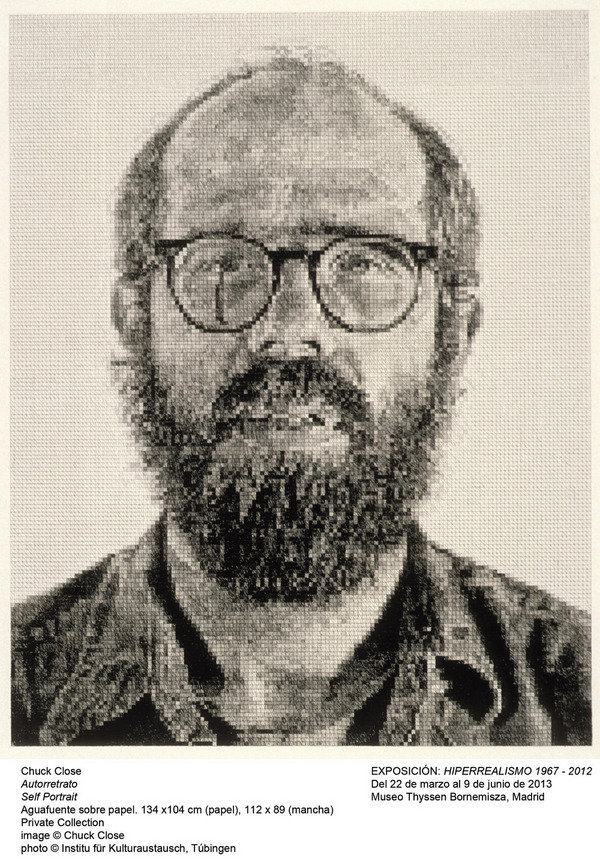

The exhibition offers a survey of Hyperrealism that starts with the great US masters of the first generation such as Richard Estes, John Baeder, Robert Bechtle, Tom Blackwell, Chuck Close and Robert Cottingham, continues in Europe with their influence on subsequent generations, and concludes in the present day.

curated by Otto Letze

In the late 1960s a group of artists emerged in the United States who painted scenes and objects from

daily life with a high degree of realism, using photography as the basis for their works and achieving

international recognition at Documenta in Kassel in 1972. For the first time, the exhibition now

presented at the Museo Thyssen‐Bornemisza offers a survey of Hyperrealism that starts with the great

US masters of the first generation such as Richard Estes, John Baeder, Robert Bechtle, Tom Blackwell,

Chuck Close and Robert Cottingham, continues in Europe with their influence on subsequent

generations, and concludes in the present day. Hyperrealism is not a closed movement and today,

more than forty years after it arose, many of the pioneering figures continue to be active while new

artists deploy the photorealist technique in their creations. Artistic devices and motifs have evolved

and changed over time but Hyperrealist works, with their incredible precision and degree of definition,

continue to fascinate the public.

Organised by the Institut für Kulturaustausch (German Cultural Exchange Institute) and curated by its

director, Otto Letze, this retrospective brings together 66 works from different museums and private

collections. Having already been seen at the Kunsthalle in Tübingen (Germany), it now travels to the

Museo Thyssen‐Bornemisza in Madrid where it will be on show until 9 June before moving on to the

Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery (UK).

Urban landscapes, shop windows, fast food

restaurants, the latest models of cars, gleaming

motorbikes, pinball machines, tin toys and bottles

of tomato ketchup are all fragments of daily life,

everyday locations and consumer items that

become artistic motifs. The Hyperrealist painters

take their subjects from the world around them,

making the everyday visible through their

paintings.

These inconsequential motifs are first captured

through photography then translated onto the canvas using a painstaking method involving a range of

technical procedures such as the projection of slides or a grid transfer system. They are generally large

format works painted with such precision and exactness that the canvases themselves have a

photographic quality. Nonetheless, they are created using a process that has nothing to do with the

immediacy implied by photography.

Considered an objective form of documenting the world, from the time of its invention photography

was used as the starting point for paintings by numerous artists, although few acknowledged this fact.

Following the pioneering use of silkscreen by Pop artists such as Warhol and Rauschenberg, it was the

early Hyperrealists who started to use the medium in an overt manner, thus making it a “legitimate”

tool. On occasions they used photographs from magazines or newspaper but they soon began to take

their own in the form of one or more images, which they then combined in the painting. Three‐

dimensional scenes were thus transformed into two‐dimensional ones and are also stripped of any

emotion: they are moments of reality frozen in time and often lack any human presence. These artists

were fascinated by the metallic surfaces of windows and mirrors that allowed them to focus on the

distorted images produced by their reflections.

Photography was thus the starting point and apparently the end result, but it was not the aim. No

Hyperrealist painter aspired to compete with it and the motivation was completely different. The

works of these artists seemed to reproduce reality but

they in fact created a new graphic reality. Through them

the Hyperrealists started to investigate specific issues

relating to the perception of reality such as objectivity,

the authenticity of images and how photography had

changed our way of seeing the world and relating to it.

The pioneers of Hyperrealism analysed all these issues and made them the subject of their paintings,

working in a more or less independent manner. In the early 1960s on the West Coast Robert Bechtle

started to produce the first truly photo‐realist paintings, while at almost the same time in New York

Richard Estes began to produce his characteristic shop windows and urban views, Chuck Close to paint

his famous portraits, and Audrey Flack, the only women in this first generation, to produce her first

works based on photographs.

Enlarged fragments of reality, objects, people and places

The first generation of Hyperrealists was almost exclusively American with some artists working on the

East Coast, primarily in New York, and others on the California coast. With slight differences between

them, they have all essentially focused on the “American way of life”; images from daily life, consumer

items and vehicles were the typical subjects chosen for

depiction.

Vehicles in the form of cars, motorbikes, trucks and

camper vans signify mobility and freedom and are thus

highly representative elements in US society and its

perception of itself. In addition, the Hyperrealists have

always been fascinated by the materials used in the

bodywork, wheel rims and bumpers and by the

reflections produced on them. David Parrish emphasises

their gleaming surfaces as the sunlight falls on them; for

Tom Blackwell motorbikes are cult objects and he paints blown‐up details and areas of them; Ron Kleemann’s

interest centres on large agricultural vehicles and trucks;

Don Eddy has had a phase in which he was most interested in the legendary Beetle car, depicting the

gleaming surface of its bodywork; Ralph Goings paints vans and camper vans as well as his celebrated

images of fast food restaurants; while John Salt looks at car breakers’ yards.

The play of light as it falls on the polished surfaces is also

the principal interest in another of the Hyperrealists’

favourite themes, namely the still life. These

compositions include everyday objects such as toys and

vending machines (Charles Bell), groups of foodstuffs

(Ben Schonzeit), consumer items and personal effects

(Audrey Flack).

We also encounter fragments of modern life in the city:

Robert Cottingham focuses on adverts and neon signs;

Richard Estes on reflections on shop windows, telephone

booths and cars; John Baeder on the outside of fast food

restaurants; and Ralph Goings on their interiors. The rural

world of the USA also appears in the work of some of the

Hyperrealists, principally those working on the West Coast, such as Richard McLean who paints modern‐day

cowboys and cowgirls; Jack Mendenhall who has been interested in conveying the atmosphere of

American homes in the 1960s; and Robert Bechtle who focuses on images of the everyday lives of the

middle class in the US.

Another favoured genre is the portrait, which always depicts sitters from the artists’ immediate circle,

or takes the form of self‐portraits. Chuck Close has been the leading representative in this field,

depicting himself and his friends on a larger‐than‐life scale with a mesh‐like technique. These faces

look out at the viewer with no emotion or movement. The Swiss artist Franz Gertsch, who worked

independently from the Americans, has also focused on portraiture. Along with the British artist John Salt, they were the only non‐American Hyperrealists of the first generation, although Salt moved to

New York in the 1960s. Their nationalities and choice of motifs both contributed to making the

movement an international one. This became more evident with the second generation of Hyperrealist

artists, who are also characterised by their technological and compositional innovations.

From the personal to the anonymous, large‐format urban landscapes

Similarly concerned to depict everyday reality,

the artists of the second generation of

Hyperrealists, who worked in the 1980s and

1990s, were more interested in translating

photographs to the canvas with the greatest

possible degree of detail. To do so, they made

use of the enormous potential offered by the

new digital and photographic techniques. They

moved away from the small scale and focused on large urban landscapes, a particularly favoured

subject for which they often used a panoramic

format. The Italian Anthony Brunelli photographs his motifs using a wide‐angled lens then combined

several images on the canvas, resulting in urban views of the different countries in which he lived.

Robert Gnieweck is attracted to urban landscapes at dusk or at night and is particularly fascinated by

nocturnal lighting displays; Davis Cone depicts the interiors of cinemas, both urban and out of town;

while despite being French, Bertrand Meniel once again concentrates on the major US cities.

Technological advances are evident in the final results of these works, which have a more precise,

detailed appearance. The limited presence of the human figure, which is a characteristic of

Hyperrealism in general, increases the impression of coldness and distance. Rod Penner uses high

resolution digital cameras, while Don Jacot paints city squares and other locations famous for their

crowds, depicting them, however, without people in them.

Absolute definition and greater precision than the human eye

The artists of the third generation working today use the

most up‐to‐date digital cameras and have taken realist

painting to another dimension, creating completely new

visual experiences. Digital images offer more information

than those based on negatives, particularly in the way the

precise outlines and high definition literally convert the

image represented into a “hyperreal” object. Roberto

Bernardi focuses on still lifes; Raphaella Spence takes

photographs from helicopters and skyscrapers; Peter Maier

is primarily interested in the representation of surfaces; and

Ben Johnson depicts buildings, producing numerous

drawings that involve the use of a computer. The city and its

inhabitants continue to be the centre of these artists’

attention as can be seen, for example, in the work of the US

artist Robert Neffson and of Clive Head from Britain.

Organiser: Institut für Kulturaustausch (German Cultural Exchange Institute)

Curator: Otto Letze, director of the Institut für Kulturaustausch

Coordination: Blanca Uría; Curatorial Department, Museo Thyssen‐Bornemisza

Number of works: 66

Publications: catalogue, published in English and Spanish

More information and images contact to:

Museo Thyssen‐Bornemisza – Press Office

Paseo del Prado, 8. 28014 Madrid. Tel. +34 914203944 /913600236. Fax+34914202780.

prensa@museothyssen.org

Museo Thyssen‐Bornemisza

Paseo del Prado 8, 28014. Madrid

Opening times: Tuesdays to Sundays, 10am to 7pm. Saturdays, 10am to 9pm. Last entry one hour

before closing.

Ticket prices:

General ticket, 8 Euros

Reduced price ticket: 5.50 Euros for visitors aged over 65, pensioners, students with proof of

status and Large Families

Free entry: children aged under 12 and unemployed Spanish citizens with official proof of status

Temporary exhibition + Permanent Collection:

General ticket, 12 Euros

Reduced price ticket: 7.5 Euros

Free entry: children aged under 12 and unemployed Spanish citizens with official proof of status

Advance ticket purchase at the Museum’s ticket desks, on its website or on tel: 902 760 511