Ulla Wiggen

dal 12/4/2013 al 24/8/2013

Segnalato da

12/4/2013

Ulla Wiggen

Moderna Museet, Stockholm

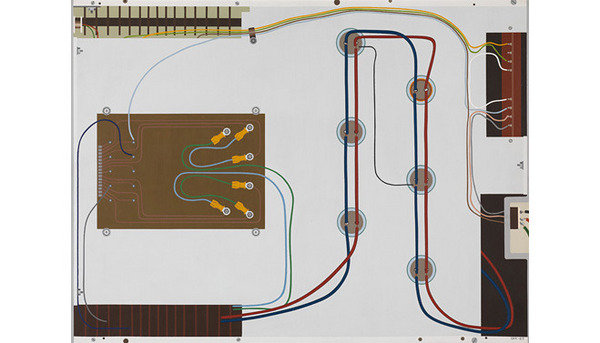

Moment. Wiggen is an artist with a fastidious and highly idiosyncratic output. During 1964-1969, she made only some 30 paintings, most of which represent the interior of various electronic devices. Her works feel vibrantly up-to-date today in 2013.

Curated by Fredrik Liew

Machines and mechanical contraptions have been prominent at Moderna Museet from day one. In the late 1950s, Fylkingen – an association for new electronic music and intermedia art – began organising concerts at the Museum. In 1961, Pontus Hultén launched the exhibition Movement in Art, where the main tenet was the machine as a revolutionary force in 20th century art. In order to give artists access to technological expertise, the engineer Billy Klüver founded E.A.T. Experiments in Art and Technology, which organised 9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering in New York in 1966, featuring Öyvind Fahlström’s multimedia performance Kisses Sweeter than Wine and in 1973, the exhibition New York Collection for Stockholm at Moderna Museet.

Ulla Wiggen was in the midst of these events. She completed her first paintings in 1963 – 1964 in Stockholm: three small gouaches on gauze of electronic components, circuit boards and the inside of an amplifier. In the autumns of 1965 and 1966, she assisted Fahlström in his New York studio and took part in the above-mentioned performance. Influenced by the American art scene, Wiggen went over to acrylic paints and began working in larger formats. But her circle of motifs remained the same until 1968, when she gradually switched from close-up studies of the inner landscapes of electrical appliances to portraits of people, via spatial depictions of technical equipment against blue skies, such as the radar mast in Radar (1968). Between 1963 and 1969, Wiggen made some 30 paintings. The exhibition features selected works from this period.

How, then, do Wiggen’s works relate to the highly-technological surroundings? In Movement in Art, Pontus Hultén describes a romantic relationship to technology as a potentially utopian or dystopian force:

“If we believe in life or art, we clearly must gain total dominance over the machines, subject them to our will and govern them so that they serve life in the most effective way. In the planning of such a world, and as a means of achieving it, artists are more important than politicians or even technicians.”

This way of seeing technology as a tool in a new world, a view typical of the era, does not seem quite as relevant to Ulla Wiggen. On the contrary, she appears both more down to earth, open-minded and more detached from such ideological aspects. Nor does she use technology in her practice; it is merely observed and represented, using conventional methods.

Nor does Wiggen share the fad for machines and their associations with production, work and sexuality – her attention is aimed primarily at electronics and a dawning digital world of a more immaterial and communicative nature. Her fascination for these “anatomical” electronic landscapes appears to rest on two factors that can push the interpretation of her works in different, and overlapping, directions: on the one hand, a strong interest in what the motif could represent (signals, interdependence, connections in the technical links, that each detail can perform a vital purpose in a larger system), and on the other her focus on the formal qualities, such as found shapes corresponding to a landscape or still life (colour, form, tactility, composition, beauty), distinctly reproduced in the painting itself.

If we look at how Ulla Wiggen’s work has been received, it is hardly surprising to find a heterogeneous picture. Interpretations span from technology romanticism to technological critique; from claims of absolute objective realism to symbolic mysticism. Analyses based on studies of 1960s cybernetics and structural linguistics alternate with references to classic existentialism and artists such as Chardin and Cézanne. Interestingly, all these interpretations, even the most contradictory ones, seem somehow reasonable and valid. Most readings agree, however, that the works, even though they lack figurative characters, have an immediate human relevance, either through anthropomorphosis of the machines, or as dealing with the complex relationship between man and machine.

Ulla Wiggen’s idiosyncratic oeuvre touches on many of the coordinates that are habitually used to “comprehend” art history – the machine theme, pop, minimalism, new objectivism, photo-realism – but Wiggen does not comply with any of these constructs. This could be one of the reasons why she has evaded the historiographical radar for so long, but it is also why her works never feel dated – unlike classic pop art and many of the machines and apparatuses that were featured in Movement in Art, Ulla Wiggen’s works feel vibrantly up-to-date today in 2013.

Opening 13 April 2013

Moderna Museet

Island of Skeppsholmen, Stockholm

Hours: Tuesday, Friday 10-20

Wednesday-Thursday, Saturday-Sunday 10-18

Monday closed

Admission

120 SEK/100 SEK (reduced admission)

160 SEK/140 SEK Combination ticket Moderna Museet/Arkitekturmuseet