There are Other Routes than Ours

dal 7/5/2013 al 17/8/2013

Segnalato da

7/5/2013

There are Other Routes than Ours

Museo Tamayo Arte Contemporaneo, Mexico City

The exhibition is designed to create a field of aesthetic tension between the collections of the Museo de Arte Prehispanico Rufino Tamayo in Oaxaca and this museum of international art in Mexico City. The show includes pre-Hispanic, modern and contemporary works of art in order to contrast the different ways that the indigenous aesthetic and mainstream international canons have been assimilated.

In the year 2000, art historian Olivier Debroise curated

the show Tamayo en el torbellino de la modernidad,

while also calling into critical question the

underlying objectives of the creation of the Museo

Tamayo. Similar to the life story of the Oaxacan

artist, the roots of this institution lie in the polemic

between nationalistic muralism (whose maxim was

based on David Alfaro Siqueiros’ statement of 1944:

“There is no other route than ours”) and the

internationalist vision defended by Rufino Tamayo.

The Museo Tamayo has acted as a forum spotlighting

international contemporary art in Mexico, subsidized

by private initiative. Though distanced from the

hegemonic years of the Mexican School, the museum’s

mission came about as a consequence of modern

disputes between figuration, realism, abstraction,

muralism, easel painting and the aspiration toward

universal art.

There are Other Routes than Ours is designed to

create a field of aesthetic tension between the

collections of the Museo de Arte Prehispánico Rufino

Tamayo in Oaxaca and this museum of international

art in Mexico City. Not unlike the artistic conflicts

that breathed life into the Museo Tamayo, the show

includes pre-Hispanic, modern and contemporary works of

art in order to contrast the different ways that the indigenous

aesthetic and mainstream international canons (whether they

be from the modern age or from more recent expressions) have

been assimilated. To this end, the works and documents included

in this show evoke the “realism” of the Mexican Painting School,

to the extent that they contrast the nationalistic rhetoric with

the abstract languages of international art and the contemporary

strategies of the symbolic and critical appropriation of the

idealism of modernity.

The selection of works is based on their material pictorial qualities,

the ambivalent relationship among abstraction, pre-Columbian

figuration, artisanal techniques, as well as rural landscapes and

folk and media depictions of advertisements and urban signage.

Furthermore, the presence of Josep Grau-Garriga’s large-format

tapestry Henequén rojo y negro (1981) alongside Gabriel Orozco’s

Mural Sol (2000) and Teresa Margolles’ Muro Baleado (2009),

prompt us to think about other narratives that reflect the

cosmological and universal modernity of Tamayo’s contemporaries.

In general, the relationships among these works are not so much

historiographic as they are based on other aesthetic routes,

postures and models which confront each other at the same

time as they show, in the international languages of art, complex

“social realities.”

The works selected for this show include modern paintings as

well as some of the Museo Tamayo’s recent acquisitions of

contemporary art. The different approaches draw on the similarities

and differences among the pieces to raise the question of how

museums, their collections and art in general establish aesthetic

models to negotiate with reality. When shown in conjunction

with specific objects, the emphasis on textural aspects and symbols

—and the apparent contradiction between Bill Brandt’s realistic

photography and Siqueiros’ claim that there was “no other

route”—reveals contrasts between the aesthetic experience of

the works and the museum’s exterior “reality” which they frame.

The show highlights the play of forces between the museum’s

interior and exterior realities. In this manner, it questions

the ways in which museums approach and configure the real,

whether in the mythicizing subjection of modernity as compared

to archaic cultures, or in the different ways that contemporary

artworks insert aspects of reality into the museum. Among the

works and textures, figures, symbols and objects there are

interwoven experiences that bring reality closer and push it

away, that mythicize the past or repudiate folk and pre-Hispanic

world views.

After modernity, the museum became a setting for the combination

of universal images and the partial visions that could both sublimate

and demythologize art’s relationship with the world.

The modern paintings in the Museo Tamayo collection introduce

archaic values that reject academicist canons and rethink the

surface of the painting as a reality in and of itself. The textural,

material and artisanal qualities of the selected works propose

an aesthetic organization that strays from the naturalistic

representation of the real.

However, these new symbolic “realities” link the past to the present,

and configure a mythical vision of modernity. The reality of

archetypal textures and symbols implies the intuition of universality,

which was the aesthetic position that Tamayo advocated to

counter the realism of the Mexican Painting School.

For its part, contemporary art embeds reality within the museum

environment. Examples of this are the “bullet-ridden brick

wall” that looks like a minimalist sculpture, and a beer ad whose

stereotypical and touristic vision of Mexico may be equated to

the tradition of official muralism, by means of the comparison

between the evocative imaginary of the exported product and

the symbolic machinery of the post-revolutionary state.

Artisanal” reproduction techniques—such as Gabriel Orozco’s

enlargements of the Cerveza Sol label and the multiple copies

made by professional sign painters of paintings by Francis

Alÿs—rely on the reproduction of images to break with the

paradigm of originality and thus call into question the value of

the unique and unrepeatable artwork extolled by modernity.

Teresa Margolles’ sculpture of bricks pierced by a hail of bullets

literally brings into the museum a section of wall that shows

the reality of a society plagued by violence. In this context, such

works force us to rethink the moral and mythologized vision

of the artistic gesture as something that defended folk and non-

Western cultures during Tamayo’s modern period.

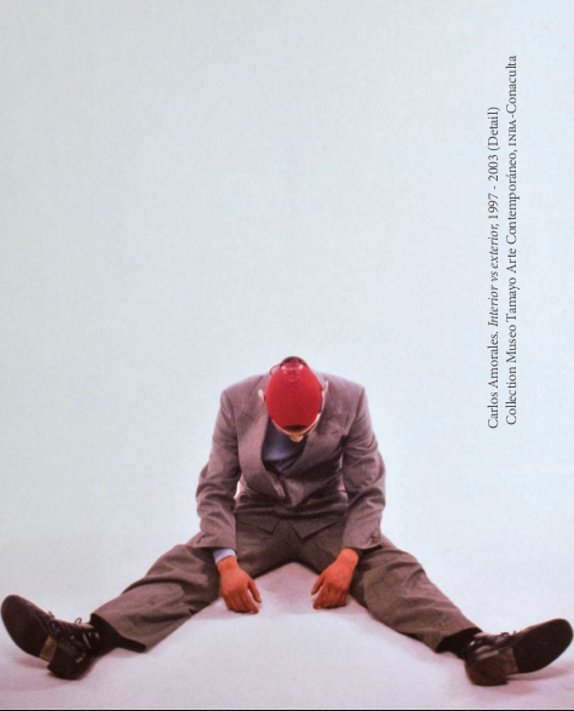

Furthermore, the “struggle” between interior and exterior

—symbolized by Carlos Amorales’ confrontation between his

self and his masked alter-ego, or Jonathan Monk’s work that

reverses and rotates the sign of the legendary Hotel Palenque—

results in obscure psychological worlds, or derelict, rural and

entropic worlds that invert the popular imaginary of the fantastic.

The modern aesthetic, which rejected Renaissance principles

of naturalistic representation, was also opposed to the realistic

conventions of muralism. Tamayo’s collection of easel paintings

asserted a new universal mystique between international art

and the different ways in which local or ancient cultures were

assimilated, while contemporary works reinforced a demythologized

and critical relationship with their own institutionalization.

As such, these practices called into question the contexts created

by collections and museums, in the sense that they are marks

of international visibility that channel the reception of our

social, political and cultural reality.

Eduardo Abaroa’s project, done ex profeso for this show, presents

a counterpoint to the institutional exploitation of pre-Hispanic

cultures, whether it takes the form of the official realism of muralism,

the anthropology museum, or the international museum as a link

between the past and the universal supposition of artistic values.

Both the cultural policies of post-revolutionary Mexico and

Rufino Tamayo’s concept of modernity found in art a successor

to Mesoamerican civilizations. This selection of pieces from the

collection of the Museo de Arte Prehispánico Rufino Tamayo

in Oaxaca casts doubt on the museum context and its strategies

of stabilization and inclusion of autochthonous cultures, which

stem from nationalistic policies that glorify the past rather than

drawing attention to their current social condition.

Communications

Sofía Provencio - Beatriz Cortés T. (5255) 5286 6519 prensa@museotamayo.org

Museo Tamayo Arte Contemporáneo

Paseo de la Reforma 51, Bosque de Chapultepec Del. Miguel Hidalgo C.P. 11580. México, D.F.

Hours:

Tuesday through Sunday, 10 am to 6 pm

Price: $19 / General public

Entrance is free to students, teachers, and senior citizens with valid identification

Sunday free to public