Jake & Dinos Chapman

dal 2/10/2013 al 4/1/2014

Segnalato da

2/10/2013

Jake & Dinos Chapman

Galerie Rudolfinum, Prague

The Blind Leading the Blind. The exhibition introduces a representative selection of their multifaceted creations. They create installations, sculptures and paintings, which through cynical and sarcastic humour highlight the current debased political, social, religious and moral situation.

curator: Otto M. Urban

Galerie Rudolfinum presents an exhibition by leading British artists Jake and Dinos Chapman entitled The

Blind Leading the Blind. The exhibition, which presents an overview of works created from the 1990s to the

present day, is the largest-ever exhibition by these two artists in Central Europe. “The Prague exhibition of

the Chapman brothers is unique in that it presents older works in a new context, meaning that their new

installation offers the possibility of creating a new point of view and the opportunity for new

interpretations,” says curator Otto M. Urban.

In five thematic units divided up into the various exhibition rooms, the exhibition presents sculptures,

objects, paintings, drawings, and etchings. In these installations, sculptures, paintings, and drawings, the

Chapman brothers use cynical and sarcastic humor to call attention to today’s depraved political, social,

religious, and moral state of affairs.

In terms of subject matter, the various cycles touch on themes that the Chapman brothers have been

working with since the beginning of their artistic career. One fundamental influence in their work is their

inspiration by the Spanish painter Francisco Goya, and the exhibition presents the brothers’ 83 etchings of

bold and distinctive variations on Goya’s famous cycle The Disasters of War.

“The Chapman brothers work with Goya in a somewhat parasitic manner. The way in which they use – or

rather, abuse – Goya’s work is far from pious or adoring. In fact, it is more of a strange, almost perverse

relationship of love and hate, the intoxicating delight of torturing the person we love the most. Goya’s prints

are drawn over and smeared, are given new motifs, and in some cases completely painted over. It is as if

Goya’s work had been only partially completed and opened up to additional artistic input and

manipulation,” says Urban.

One important element in their art, which the Chapmans have been working with since the 1990s, is the

“study” of mutant mannequins, genetically mutated figures through which they explore the boundaries of

generally accepted morality and try to provoke a change in the perception of ingrained gender and sexual

stereotypes. At the Galerie Rudolfinum, this series of works is represented by libidinal objects of Siamese

beings and figures of children with distinctive phallic and other symbols on their faces.

Another important theme in the art of the Chapman brothers is Nazism and fascism. The cycle exhibited at

the Rudolfinum offers a precipitous look at the transhistorical concept of “absolute evil” symbolized by the

Nazis and the horrors of the Holocaust. The monumental installation consisting of two dozen Nazi figures

was specially adapted for the needs of the Galerie Rudolfinum.

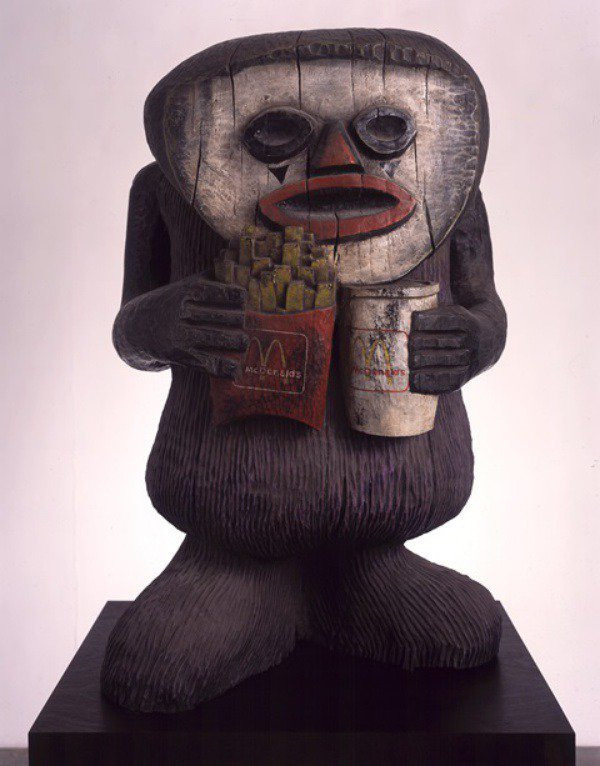

The Prague exhibition also features a sarcastic excursion into the anthropological world of fetishes in

contemporary society, represented by bronze sculptures resembling a collection of African art, in which we

discover the corporate logos of fast-food restaurant chains.

Not even intimate aspect of life such as sex and death are taboo for the Chapmans, whose objects with these titles uniformly evoke shocked reactions.

“The art of the Chapman brothers is accompanied by words such as scandal, controversy and provocation –

in the critical sense, of course – as well as superficial endeavors whose only aim is to make themselves

visible. In the end effect, the only thing that is scandalous is the attitude of certain critics and moralizers,”

says exhibition curator Urban. Critic and journalist Johann Hari even compares the art of the Chapman

brothers to “punk art that spits in your face”. As the Chapman themselves say, their art is more analytical

than critical.

Just as Bataille described his relationship to aboriginal rituals in the hope that he might, if only for a

moment, return modern society the symbolic power that it lost long ago, so too – in their cycle The

Chapman Family Collection – do the Chapman brothers work in their own unique way with similar cultural-

anthropological themes. In so doing, they call into question their validity and, above all, their topicality. This

set of 11 bronze sculptures reminiscent of African fetishes contains motifs based on the corporate symbols

of the global fast-food giant McDonald’s. For the Prague exhibition, each work was labeled with an eight-

digit number representing a functioning telephone number to a selected McDonald’s in Prague. Everything

is further amplified by the manner in which the work has been installed and illuminated. The viewer does

not see merely a “collection” of African art, but also consumes the images of French fries and hamburgers

found on these objects. Some of the objects are references to the work of other artists, such as Constantin

Brancusi’s The Column of the Infinite from 1938, which the Chapmans have assigned the head of Ronald

McDonald, whose uniform clown grimace they place on the level of religious rite. In this context, the

questions of “commodity fetishism” evoked by the Chapman brothers are less a criticism of globalized

consumer society than a sarcastic analysis of its current state.

The collection of sculptures is supplemented by a series of drawings entitled Drawings from the Chapman

Family Collection, in which the Chapmans combine corporate symbols with fetish sculptures and let them

come alive along with other figures in dark and personal mini-stories.

Goya’s influence on the Chapman brother’s work can also be seen in the sculpture entitled Sex, which is

based on the earlier work Great Deeds Against the Dead, which was inspired by Goya’s cycle The Disasters

of War. Here, the Chapmans’ interpretation of Goya is truly radical. The original work, which showed three

dead bodies of castrated soldiers, has been transformed into a massive element of decay. “Sex presents the

extravagant expressions of death, reminiscent of the paper dolls during celebrations of the Day of the Dead

in Mexico. We see three corpses that are gradually gnawed to the bone by an army of insects and masses of

small vermin, with the teeming creatures forming a kind of wave of purification; the worms, slugs, flies,

spiders, and beetles look like they are plastic, purchased at a shop selling Halloween goods. In reality, they

are cast bronze,” says art historian Christoph Grunenberg. This fleeting spectacle of life presents a

decomposed picture of uncompromising decay in its pure, archetypal form.

The work can be seen both as an expression of caustic naturalism as well as an example of dark humor and

the depraved visuals of the B horror movies that the Chapmans often use as a source of inspiration. The

worms crawling out of the skull have horns, the bloody vampire eyes gaze at a red clown nose, another skull

has been endowed with a zipper and several pairs of vampire teeth borrowed from a toy store. When

looking at the zombified skeleton, the viewer may remember cheap, almost Dadaist scenes from horror

movies such as Jean Rollin’s Zombie Lake (1981).

“Unpleasant things challenge us, tell us more about our lives, dreams and subconscious than looking at

pleasant things does,” says Jake Chapman.

At first glance, the object from the cycle Death plays with the cheap aesthetics of “eroticized” kitsch – here

embodied by a male and female blow-up doll engaged in sex on an inflatable mattress. The visual illusion

goes down to the details: the dolls are not inflatable but made of cast bronze, and their bed of love is not

light and filled with air, either. It, too, is made of heavy bronze. This illusion is wed with another contrast –

the private is put on public display; the playful becomes clumsy and inflexible. A noble material such as

bronze is painted in thick layers of paint to give it the lascivious character of latex.

“It is a sophisticated play with the delusions of what we see in reality and what we think we see. What the

viewer recognizes first is an illusion that sheds itself in order to cover up and complicate the reading of

innate meanings. The Chapmans play their own game with the viewer while constantly changing the rules.

In fact, understanding the ‘rules’ of this game is one possible way of understanding the work of the

Chapman brothers,” says Urban.

The monumental installations Fucking Dinosaurs and Flock Off present 20 Nazi figures in black uniforms

and with burnt, zombie-like faces and with smiley-faces instead of swastikas, who look at the exhibited

objects and drawings in horror but with a sense of interest. The work is a reference to the exhibition of

“degenerate art” – Entartete Kunst – held in 1937 in Munich and in other German and Austrian cities.

Within the broader context, we are witness to a transhistorical phenomenon in which the subject of Nazism

ceases to be a mere reference to the Second World War and the horrors of the Holocaust and becomes a

global symbol for modern evil. We even arrive at questions as to the very existence of evil as a notion

existing outside of the historical context. “It can be expressed simply – if we ask ourselves the question

whether there existed evil during the time of the dinosaurs; whether there was a hell. We can go even

further and ask ourselves whether evil is a mere construct of our minds”, says the curator. Any

interpretation of the cycle is equally ambiguous. “The smiley faces that the Nazis wear on their sleeves

instead of swastikas make it difficult to judge whether the work is good or bad. Is he a good Nazi because he

knows how to smile nicely and is wearing a smiley face, or is he a bad Nazi since his grimace is worse than

the Devil’s smile?” asks Jake Chapman.

In another series, Minderwertigkinder, a group of girls is looking at paintings whose innocent children’s

faces metamorphose into animal faces. Here we have a direct reference to horror and fantasy movies, as in

Wolf Child – a picture of a girl whose innocent child’s face is inexorably metamorphosing into a terrifying

wolf’s head. Here we find a visual and mental parallel to Neil Jordan’s Gothic fantasy horror Company of

Wolves (1984). Like the other girls from this series, this one is wearing a brown sweatshirt with an

embroidered swastika and the text They Teach Us Nothing.

Etchasketchathon is a series of children’s illustrations made using the chine-collé whose name comes from

the popular children’s magnetic drawing tablet Etch-a-Sketch. The scenes from this series are far from

idyllic, however, despite what we might expect from children’s illustrations. The figure of the girl plays with

a headless fawn, some meat is rotting nearby, a plush bear is crucified on a swastika, and some illustrations

feature mutated figures of sculptures.

In the series of drawings Bedtime Tales for Sleepless Nights, we are witness to a combination of written

text and children’s illustrations in which simple and easily remembered text containing frightening nursery

rhymes is accompanied by colorful drawings reminiscent of children’s book illustrations. The texts were

written by Jake Chapman, who has written several books.

The series Southsea Drawings depicts children’s connect-the-dots drawings, accompanied by titles taken

from the opening words of selected short stories by H. P. Lovecraft.

The Shape of Things to Come, the title of a 1979 film by director George McCowan, is also the title for a

diorama created by the Chapman brothers in 1999–2004. Diorama are usually found in museums and are

supposed to evoke a particular historical or mythological event. Time stands still and inspires the viewer to

consider what came before and what will come after. Jake and Dinos Chapman have been systematically

working with this “medium” since the late 1990s. In their hands, the display cases are filled with thousands

of figures and apocalyptic landscapes. The painstakingly detailed scenes and countless constellations refer

to scenes from epic war movies. “In the architecture of the destroyed church, the diorama The Shape of

Things to Come is reminiscent of a war scene from Elem Klimov’s 1985 Soviet film Come and See. The

display case is filled with figures of monsters and their victims. The terrible theater is a textbook display of

the extremes of human behavior,” says the exhibition’s curator.

In their works dedicated to the “study” of mutant mannequins – in particular the sculpture Return of

Repressed – Jake and Dinos Chapman present a burlesque cabaret of the human anatomy the hands of

science. The centaur-like, mathematically standardized figures of indeterminate age and gender contain the

harbinger of something frightening. Battered codes of human DNA ripen into naked, genetically mutated

figures of zygotic beings, some of which could have come from the Island of Doctor Moreau. Return of

Repressed – a Siamese being with one body and two heads whose shared face is dominated by a female sex

organ – may be a reference to the iconic dolls of German-French artist Hans Bellmer and his strange

anatomical cabaret.

The Freudian notion of sublimation can also be found in another work with a strong libidinal charge, Bloody

Fuckface – a child with a pronounced male sex organ in its face, which also features an anal opening. The

work’s impact is further amplified by its installation in a display case filled with red color resembling a pool

of blood.

Among other things, the sense of dread evoked by these plays of nature (or rather, of the Chapman

brothers) inspires us to wonder about the inspiration for such horror. “Mutant mannequins have their

history, whose roots go back to Renaissance wax figures that were used as study aids by students of

medicine. Today, however, they strike us as distinctive sculptures, have lost their original educational

meaning, and are more reminiscent of creatures from horror films inspired by the writings of American

author H.P. Lovecraft,” says exhibition curator Urban.

The polymorphic sexual beings’ libidinal character allows us to find psychoanalytical interpretations and

meanings. In this context, art historian Christoph Grunenberg hit the nail on the head when he says that the

works may serve as “transcripts” of the contents of Freud’s unconscious. As presented by the Chapmans,

sexuality, gender and libido are not fixed entities, but rather mental concepts that evoke a whole series of

ambivalent feelings – from fascination and excitement to disgust or absolute failure to understand.

In relation to the mutant mannequins, we can also speak of the possibilities of a Bataille-like transgression

that is closely tied to the experiences of sexuality and the overcoming of sexual taboos, including (in the

broader sense of the word) moral taboos. Of course, the questions of “bioethics” and genetic engineering

offer themselves as well. “People are very nervous about these gray areas of their own morality. They

desperately try to put everything into a comfortable box, but the moment you confront them with

something that doesn’t fit, they start to shriek threateningly and to wave their arms, which is precisely the

feeling that we want to evoke. This effect strikes us as for more interesting than the object itself,” explains

Jake Chapman.

The exhibition is accompanied by videoprojections “ChapmanBox” at the small gallery where are screened following interviews and short documentaries.

Jake & Dinos Chapman, White Cube Channel films

On End of Fun: 10:41

On Fucking Hell: 3:26

Jake not Dinos: 8:01

Dinos not Jake: 5:54

Camera / Edit: Jon Lowe

Courtesy White Cube

Some pieces in this exhibition could evoke strong emotional reactions. Galerie Rudolfinum recommends that highly sensitive persons and guidance of the children of up to 15 years of age think seriously about visiting this exhibition!

The exhibition catalogue Jake and Dinos Chapman Blind Leading the Blind Because includes in addition to essays of curator Otto M. Urban and reproductions of all exhibited works, unique exhibition installation views.

Galerie Rudolfinum thanks the Jake and Dinos Chapman Studio; the White Cube gallery, London; Paragon|Contemporary Editions Ltd, London; Olbricht Collection and all others who lent the works for this exhibition.

Image: 2002, Painted bronze, © Jake and Dinos Chapman, Courtesy White Cube

Contact for information: Marian Pliska, T + 420/227 059346 pliska@rudolfinum.org

Media contact: Nikola Bukajová, T +420 227 059205, M +420 725 365792 bukajova@rudolfinum.org

Galerie Rudolfinum

Alšovo nábřeží 12 CZ 110 01 Praha 1

Opening hours:

Tue – Wed, Fri – Sun: 10am–6pm

Thu: 10am–8pm

Monday closed

admission:

Full 140 CZK

Reduced 90 CZK

Gift Tickets for the exhibition 140 CZK (valid during the exhibition)

Ticket is valid for one re-entry to the event.