Archive State

dal 20/1/2014 al 5/4/2014

Segnalato da

Arianna Arcara

Luca Santese

Simon Menner

David Oresick

Thomas Sauvin

Akram Zaatari

Hamza Walker

20/1/2014

Archive State

The Museum of Contemporary Photography - MoCP, Chicago

The artists featured use found photographs and digital imagery to investigate significant political and economic transitions specific to particular places. They all appropriate the original contexts of selected images and use them for a new purpose. Playing with histories, both public and private, they complicate issues of authorship and original intent.

The artists featured in Archive State use found photographic materials and videos to investigate significant political and economic transitions specific to particular places—the waning epicenter of the twentieth-century American auto industry, China’s burgeoning capital city after the Cultural Revolution, young American soldiers in a war zone in Iraq, an oppressive East German state during the Cold War, and the activities of Arab youth on the eve of the Arab Spring. Whether the artists collect discarded photographs, work with state-run archives, or create montages of videos posted to the internet, they all appropriate selected imagery and edit the original context with their personal observations. Playing with histories, both public and private, Arianna Arcara and Luca Santese, Simon Menner, David Oresick, Thomas Sauvin, and Akram Zaatari complicate issues of authorship and original intent.

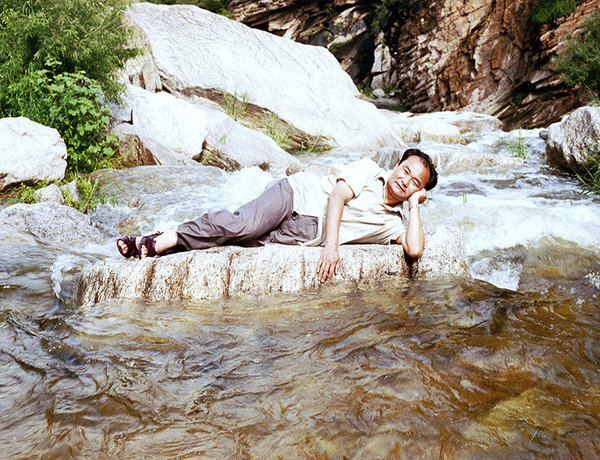

For the past three years, collector Thomas Sauvin (French, b. 1983) has visited a Beijing recycling center each month and purchased color negatives for the value of the silver they contain, effectively rescuing discarded filmstrips from being melted down for silver nitrate. To date Sauvin has accumulated over a half a million photographic color negatives and has obsessively digitized each one to create an archive. The images are mostly snapshots taken by unknown photographers that were made within a twenty-year period—from the early 1980s when 35 mm color film became popular in China to the early 2000s, as consumer digital camera became ubiquitous—and thus Beijing Silvermine can be read as a unique portrait of China’s capital city from the end of the Cultural Revolution to the country’s rise in the global economy. Sauvin has discovered that the majority of the vernacular pictures document life’s important occasions— “Kodak Moments” such as babies being born, family gatherings, weddings, and visits to Tiananmen Square—while other images contain markers of prosperity and modernization that, when taken together, trace the rise of national consumerism and global tourism. Pictures of people standing in front of their new refrigerator or television or posing with the masses next to Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa at the Louvre in Paris, point to China’s post-socialist era and deepening engagement with global culture. Sauvin displays thematic groupings of photographs printed in various sizes, which appear on the gallery walls, in photo albums, or as animations of still images. Sauvin produced the animations in collaboration with two artists that share his interest in interpreting this massive archive. With Leilei (Chinese, b. 1985) Sauvin cocreated Recycled, a three-channel video installation that combines hundreds of similar images into videos presented on small screens submerged in a large pile of snapshot-size pictures on the gallery floor. In the vein of Monty Python shorts, Cari Vander Yacht (American, b. 1981) contributes quirky animations inspired by random images sent to her by Sauvin, that humorously bring particular snapshots to life. Having never been to China, Vander Yacht is gaining a view into China through the Beijing Silvermine archive. Her detached understanding of the changes in Beijing emphasizes the ways stories of a changing state flow out to foreigners through images. The rapid cultural changes that are visible in Sauvin’s project contain a clear endpoint as imaging technologies have shifted and the mine is progressively diminishing. Sauvin has explained, “I’ll stop collecting negatives when there are no more to collect. I get less and less each month and it is quite likely to be over soon. Eventually this project will witness

the death of analog photography in China.”

Like Sauvin, artist team Arianna Arcara and Luca Santese (Italian, b. 1984 and 1985) focus on the shifting conditions of urban life in the late twentieth and early twenty-first century but paint a different picture of a place affected by changing global economies. In 2009 the artists visited Detroit, Michigan, to photograph the notoriously destitute Motor City. As they began their exploration of the city, the artists happened upon thousands of photographs, letters, and police documents such as mug shots and evidence of crime scenes or accidents, as well as family albums dating from the 1970s to the 2000s, all found near vacated buildings and in desolate neighborhoods. Rather than making pictures, the artists chose to present a selection of the found materials as their portrait of Detroit. In contrast to the economic boom that foregrounds the lives depicted in Beijing Silvermine, Arcara and Santese’s collection physically and metaphorically depicts a failing city not only through the abandoned objects, some of which are discolored and deteriorated from long exposure in extremely volatile environments, but also through the information these documentary objects contain.

Notably, all of the materials found by Arcara and Santese, both personal and institutional, were abandoned. They were not spontaneously unmoored by a natural disaster such as Hurricane Katrina or the Tōhoku earthquake-tsunami, both of which caused personal items and confidential documents to be strewn onto streets. In Detroit, the situation points to another kind of human adversity, as the records were neglected and unprotected, revealing a state’s attitude toward social standing and rights to privacy.

Arcara and Santese's resulting installation Found Photos in Detroit (2009-10) consists of 200 original photographs and documents selected from the thousands of collected materials. The photographs are carefully put into framed groupings with personal snapshots and notes intermingled among mug shots, pictures of crime scenes and accidents. The use of found photographs and documents by Sauvin and by Arcara and Santese reveal personal and in some cases sensitive details of unidentified individuals, raising ethical concerns of privacy and issues of power. Once the objects are repurposed, the individuals depicted in them have no power over how their images are used, an issue regarding a lack of authority that extends back throughout the history of photography. The majority of the people pictured in Found Photos in Detroit are African Americans and together the photographs underscore the dysfunction caused by inequality, racism, and disenfranchisement. In re-viewing Arcara and Santese’s project, Minneapolis artist Vince Leo writes, “As so often in the past, these African Americans have been reconstructed into a narrative not of their own making, revealing their utter representational powerlessness, no matter the intentions of the current powers that be. That is the agonizing contradiction at the heart of Found Photos in Detroit: that the source of its power as a social critique is made possible only by appropriating the despair of the abandoned. To hold those contradictory positions in your mind is to grasp the cost of representation; to hold them in your heart is to know truth as an oppressive other.”

Berlin-based artist Simon Menner (German, b. 1978) also worked with highly sensitive and controversial materials when he researched the archives of the former German Democratic Republic’s State Security Service (STASI). This archive was made public, with certain limitations, after the Berlin Wall came down in 1989. Known to be one of the most effective Cold War surveillance apparatuses, the STASI had more agents, proportionally to its country’s population, than either the CIA or KGB. Menner has reproduced select pictures from the archive and in a similar fashion to Sauvin, catalogues the images into varied groupings. Pictures from seminars and handbooks originally taught agents how to don disguises to appear inconspicuous. Images detailing surveillance methods are juxtaposed with documentary images of secret house searches, surveillance of the

United States Embassy, agents shadowing a subject, and perhaps most interestingly, spies spying on spies. A great variety of different camera types and films were used by STASI depending on their objective. For example, small spy cameras were made to fit inside a jacket to enable observations through a buttonhole, and Polaroid pictures were used in the beginning of secret house searches to allow the snoops to put the house back together exactly as it was found. Most of the pictures speak to an invasion of privacy enacted against those under surveillance but, in the vein of Arcara and Santese’s Found Photos in Detroit, Menner’s choice to publicly display selections from the STASI archive raises similar ethical questions, since it is, in effect, a second invasion of privacy. Menner is aware of this dilemma and believes that it is important to exhibit the photographs in order to stimulate public discussion about contemporary government surveillance and the rights of citizens.

Looking at a very different period of war and turning to found materials originally made public on the internet, artist David Oresick (American, b. 1984) discovered a poignant entry point into the personal experiences of American soldiers deployed to Iraq—amateur videos posted to YouTube by soldiers and members of their families. Oresick’s video bombards the viewer with a great variety of appropriated and edited clips, such as soldiers pulling pranks on each other, singing obscene lyrics, and visceral footage made during combat, which he intersperses with blank, white spaces of time to allow for contemplation. By making editorial selections from a seemingly endless archive of materials available through the web, then cutting, combining, and perhaps most significantly, changing the context in which the videos are viewed, Oresick has created a raw, poetic view of contemporary war. Because Oresick is not a veteran and does not have firsthand experience of the war in Iraq, Soldiers in their Youth also situates war as a distanced act that enters the lives of many American citizens through imagery and reportage. In this way, the personal posts on YouTube can serve as a counterpoint to mass media portrayals of war. His video raises questions about the American involvement in Iraq and illustrates the toll of war by portraying the soldiers as complex men and women, who are at once, in the words of Oresick “naive and wise, frightened and brave, crude and compassionate.”

Also looking at youth and reinterpreting material originally made for public consumption, artist Akram Zaatari (Lebanese, b. 1966) recontextualizes a wide range of documents, from found photographs to videos posted on the internet, that provide a window into certain cultural and political conditions in Arab countries and investigate the ways these materials intersect and disrupt predominant cultural narratives. For Zaatari, working with preexisting material becomes an extension of his experience, knowledge, and perception of the world around him, and he uses the individual stories to penetrate wider cultural concerns. In Archive State, Zaatari displays his somewhat playful four-channel video Dance to the End of Love (2011), which uses a method that resembles Oresick’s Soldiers in their Youth, as he, too, compiles materials found on YouTube, but in this case posted by young Arabs filming themselves in Egypt, Libya, Oman, Saudi Arabia, and Yemen on the eve of the Arab Spring. Zaatari is intrigued by how the subjects see themselves and what they choose to present to the public through their videos. Most of the videos were made with mobile phones and depict boys and young men acting as heroes and displaying machismo for the camera. Clever films that show teenagers magically playing with balls of fire or having the ability to be transported to new locations are put next to scenes of men flexing their muscles compulsively for the camera, competitively driving pickup trucks tipped on two wheels, or young men and women singing and dancing. For Zaatari, “Dance to the End of Love is as much about magic, dance, and singing as it is about loneliness of the oppressed and the hundreds of thousands of people that seek to act as heroes for the computer screen.”

Zaatari began collecting these videos in the summer of 2010 and presented this project for the first time in January 2011 when the Arab uprising began in Egypt. In an effort to find how the original creators of these videos were responding to the rebellion he searched for recent postings by them, and to his initial surprise did not find any. In Zaatari’s words, “The reality of self-representation is too complex, I am afraid, and at times of great insecurity many have actually no opinion. We forget. We forget that in the shadow of the millions out on the streets, there are millions with no opinion. And we forget that even the millions who have been recently on the streets shouting with slogans for a cause could go tomorrow shouting loudly for other slogans. That’s so sad, like the end of love is.”5 Both Zaatari’s and Oresick’s compilations examine the role social media plays in defining a current state of affairs and the easy circulation of digital imagery today. As Zaatari explains, this circulation of imagery “represents a revolutionary phenomenon in the history of image production and diffusion, and that will definitely impact not only how images look, or how they are constructed, but also our logic, our human relationships, our recording habits, or simply our lives.”

All of the artists whose work appears in Archive State provide unique portals into individual stories, and in the process they not only expose dominant characterizations of a society but also occasionally stand in contrast to them. At times sinister, and in other moments sensitive, the artworks reveal how found records, many of them anonymous, contain particular insights into the circumstances of a time and place—and tell compelling stories of shared history.

(Natasha Egan, Executive Director)

Support for Archive State is provided by the Italian Cultural Institute Chicago and the Goethe-Institut Chicago.

A special thank you to the Columbia College Chicago Art and Design department and the Photography department for their continued technical support.

Opening Tuesday 21th January 2014

The Museum of Contemporary Photography - MoCP

600 S. Michigan Ave (Columbia College), Chicago

Open hours: Monday to Wednesday and Friday to Saturday 10 - 17, Thursday 10 - 20 and Sunday 12 - 17