Barbara Probst

dal 22/4/2014 al 5/7/2014

Segnalato da

22/4/2014

Barbara Probst

Galerie Rudolfinum, Prague

Total Uncertainty. Probst works with multiple images of a single scene, taken at the same time using several synchronized cameras. The exhibition presents Probst's installation What Really Happened as well as some 25 photographic series from her long-term project Exposures.

Curated by David Korecky

Barbara Probst works with multiple images of a single scene, taken at the same time using several synchronized cameras. This approach breaks down the viewer’s singularity – it is not clear where the viewer is located within the given situation, which viewpoint is “his”. Probst essentially engages in a sophisticated violation of the viewer’s privacy. Frozen time par excellence, the multiplication of images, unclear boundaries as to where the composition begins and ends, references to the aesthetics and linear narrative of movies – all these are distinctive elements found in the work of Barbara Probst.

The exhibition Total Uncertainty presents Probst’s installation What Really Happened (1997-8) as well as some 25 photographic series from her long-term project Exposures (2000-2013). The exhibition, which is curated by David Korecký, is accompanied by texts by Barbara Probst, philosopher Miroslav Petříček, and art theorist Martin Mazanec.

Barbara Probst was born in Munich in 1964, and today lives in both Germany and the United States. In presenting Probst’s visually rich and conceptually rooted work, Galerie Rudolfinum follows up on its series of solo exhibitions by photographers such as Jürgen Klauke, Gregory Crewdson, Shirana Shahbazi, and Bernd and Hilla Becher.

Total Uncertainty

For the past 14 years, Barbara Probst has worked with multiple images of a single scene, taken at the same time using several synchronized cameras. This approach breaks down the viewer’s singularity – for the viewer it is not clear where he is located within the given situation, which viewpoint is “his”. Probst essentially engages in a sophisticated violation of the viewer’s privacy. On the other hand, in so doing she multiplies the moment of astonishment that we feel when admiring a photograph that has captured the “decisive moment” that we have known since the time of the legendary Henri Cartier-Bresson.

Probst studied sculpture in Munich, and spent a year studying with Bernd Becher’s in Düsseldorf. The photograph course was made famous in part by the work of Bernd and Hilla Becher, who synthesized the genres of documentary and conceptual photography in a way that was later called the Düsseldorf School – a phenomenon that changed people’s understanding of photography not only in Germany, but eventually throughout the world as well. Barbara Probst nevertheless differs significantly from the Bechers’ other students. The photographers of the Düsseldorf School have always worked on the assumption that photographs capture the real world, or at least a part thereof. Although her work may strike us as hyper-topographical, Probst does not depict experienced reality but creates an imagined mental space that coexists in parallel with – or even in opposition to – the real world.

What really happened

In the 1990s, Probst created several installations that included photographs. Their main media were the space of the room, objects of various character, and the photographic image. In these works, Probst worked with shifts in the objects’ scale and with the performative aspect of the viewer’s presence within the installation. These installations are clearly the work of an artist who thinks more like a sculptor than a photographer. Galerie Rudolfinum presents Probst’s installation entitled What Really Happened (Was Wirklich Geschah) from 1997-8, which is the last work she completed before fully focusing on her series of Exposures.

What Really Happened is a looped sequence of 81 slides, projected in three-second intervals, simulating endless movement backwards. The photographer constantly aims the lens at one spot while backing up, but thanks to the photographs’ clever arrangement into exterior shots, this backwards movement does not lead from close-up to wide shot. Probst does not use zoom; each image, even if it looks like a close-up view of the next one, represents an independent unit. She moves in order to, paradoxically, always end up in the same situation – always face to face with a same-sized segment of the world. What Really Happened uses a different approach to show what we should pay attention to in her later Exposures: Probst here does not turn to the medium, but to the world; she does not explore the photographic image as such, but the individual’s relationship to and his place in the world.

Exposures

Probst speaks of the universe that opened up before her after completing Exposure #1, and so we can describe the fundamental problem that these works present to the audience as a “black hole”. With the works from the Exposures series, Probst allows us to identify cracks in our ingrained way of reading photographic images and above all she calls into doubt the way in which we are used to internalizing observed images.

The slide show of What Really Happened introduces the main part of the current exhibition at Galerie Rudolfinum, which consists of nearly 25 photographic series entitled Exposures. Probst began working on the series in 2000, and has created more than 100 series of photographs, all of them created using the same method: She sets up two to 13 cameras in one space and takes simultaneous pictures using a radio-controlled shutter release. The resulting photographs of one moment are presented in rows and grids that have a meticulously defined order “like the words in a sentence”. For the most part, the installation consists of large-format images, so the viewer must move in order to view – either by turning his head or by taking a step forwards, backward, or to the side. Even in this formally simple work, Probst remains true to the performative principle of interacting with the viewer.

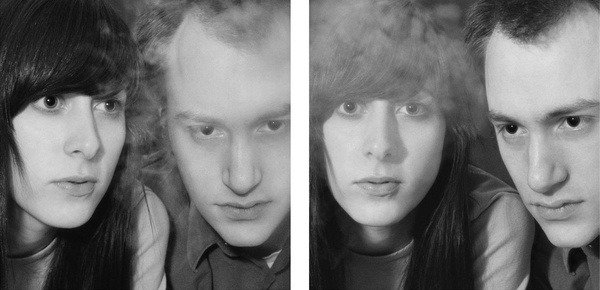

The more reduced the form, the more layered the game that she plays with the viewer. In the series that explore the movement of people on the streets of New York, we cannot escape the temptation to imagine the images creating a story. In the different images, the background changes and the stage remains the same, but it looks completely different. By comparison, her portraits present us with an intense psychological game. In creating multiple images of the same face, Probst tears down the fundamental value of portrait photography because it prevents the viewer from communicating with the model – the eyes are no longer the gateway to the soul. In one photograph the model’s eyes gaze fixedly at us, but in the one right next to it the model gazes at someone else. They are the same eyes in the same moment, but where is the viewer? Is it possible to imagine that one situation captured on several photographs is always the same? This would require us to cast off the concept of singularity and to try to see the world from several points of view at the same time. Such attempts will necessarily touch on other worlds, on the boundary to hallucinations, schizophrenia and total alienation.

In Exposures, Probst gives up on the role of the traditional photographer – the role of the expert viewer who selects and frames a shot that we might not have noticed or could not see in real life. She abandons us as guide, her absence underscored by the fact that many of the photographs show cameras on tripods but without anyone operating them. This violates our trust in the photographer as someone who has selected the image for us. In addition, the viewer is presented several parallel versions of what the world looks like. Is Probst trying to confuse the viewer, or does she aim to lead us out of the fallacy of subjective perception?

For her part, Probst frequently speaks of being inspired by the work of the French director Jean-Luc Godard. In Cinema 2: The Time-Image, theorist Gilles Deleuze described Godard’s work with images using the concept of the “crystalline image”. To borrow Deleuze’s classification, as images of a film lacking the element of time and any relationship to an author, Barbara Probst’s photographic series are crystalline images par excellence. Her photographs, made in the absence of a creator and any avowed timeline, deconstruct reality by constantly reshaping it – according to Deleuze, they are literally a “crystalline description [that] stands for its object, replaces it, both creates and erases it, […] and constantly gives way to other descriptions which contradict, displace, or modify the preceding ones. It is now the description itself which constitutes the sole decomposed and multiplied object.”

Though she works with a recording of the real world in an absolutely coordinated and meticulous manner (she precisely identifies each work’s time and place in its title), Probst creates an imaginary world that exists independently of the physical environment that stood model for it.

Uncertainty and the way out

Just as one photograph cannot provide an understanding of Barbara Probst’s photographic oeuvre, so, too, we cannot hope to understand her motivations and objectives – i.e., what precedes her photographs and what comes after them – with just one interpretation. In other words, if Probst’s photographs confront the viewer with the realization that he is not the only one currently looking, we should also bear in mind that we are not the only ones to interpret her work. The uncertainty inherent in her work thus also rests in our loss of control over (understanding, internalization of) our immediate surroundings.

Aware of the range of possible interpretations of Probst’s work, we offer the visitor two essays by philosopher Miroslav Petříček and theorist of the moving image Martin Mazanec, written on the occasion of the exhibition at Galerie Rudolfinum. As a third extension of the visual world of Barbara Probst, we have also reprinted some of her reflections contained in an interview with Fréderic Paul, originally printed in a comprehensive book published last year by Hatje Cantz Verlag.

While the history of modern photography is inherently associated with the “decisive moment”, over the past two decades we have increasingly encountered a tendency to ignore the decisive moment or at least to suppress it. Probst tackles this eternal theme in an utterly original manner, using it as a foundation for the (non)temporality of her photographic series while at the same time fundamentally complicating the question of the viewer’s relationship to (or his internalization of) a work of art.

Seen from this angle, Probst’s works are an important contribution to the theory of visuality and the deconstruction and endless reconstitution of the image and the reality it depicts or creates.

David Korecký, exhibition curator

Press contact:

Nikola Bukajova T: +420 227 059 205 bukajova@rudolfinum.org

Opening: wednesday 23 april 2014, at 18

Galerie Rudolfinum

Alšovo nábreží 12 CZ 110 01 Prague 1

Opening hours:

Tue.-Wed., Fri.-Sun.: 10-18 h., Thursday: 10-20 h.

Monday closed

Combined admission Galerie Rudolfinum + The Museum of Decorative Arts:

Regular 180 CZK

Discounted 100 CZK

School group with pedagogue: 30 CZK / person