Scott King

dal 15/5/2014 al 11/7/2014

Segnalato da

15/5/2014

Scott King

Between Bridges, Berlin

This show is called 'Totem Motif' and all the work deals directly with monuments or notions of 'public art'? Yes, this show is made up of three different works - I'll describe each of them to you.

This show is called “Totem Motif” and all the work deals

directly with monuments or notions of ‘public art’?

Yes, this show is made up of three different works - I’ll

describe each of them to you.

“Study of Blackpool Tower”: I did this in December last year.

I’d gone to Blackpool to interview the band Sleaford Mods

for Arena Homme+, a magazine I write for occasionally. The

band were playing a short tour of the North of England and

Scotland, and I became very fixated on seeing them in Black-

pool. It made perfect sense to me: Sleaford Mods make songs

about the minimum wage, cultural disappointment and ‘social

entrapment’. Blackpool is officially Britain’s second poorest

town, it’s a completely broken, downtrodden and rough place,

but also a very famous seaside town, a place that was essen-

tially invented by Victorian industrialists for the workers from

Lancashire’s cotton mills to go on holiday for one week each

year and, well, go mad. It was, and still is, a sort of ‘safety

valve’ for the working classes, a place where people can go to

behave very badly ... get drunk, fight, fuck each other. It’s an

incredible place, but also deeply sad - and I was attracted to

this dichotomy. I went up there the day before the band were

due to play - I wanted to photograph the semi-derelict streets,

the neon, the drunks and the sad-fun. Unfortunately, all the

photographs I took were terrible, sub-Martin Parr clichés of

Northern working class misery ... my photographs looked

like Morrissey’s holiday snaps. But as I flicked back through

the images, wondering what to do, I noticed that almost all

my pictures had Blackpool Tower in the background ... and I

realised that this was the whole point. The Tower is virtually

inescapable, no matter where you stand in the town, no matter

how rotten the street is that you’re on; you are almost always

confronted by this majestic and beautiful mini-Eiffel Tower.

It struck me that Blackpool Tower (built in the 1890s) was

perhaps an early example of a monument being ‘deployed’ in

the same way that the British government now commission the

likes of Anish Kapoor and Antony Gormley to build enorm-

ous public sculptures in poor or post-industrial areas. That is:

they erect these enormous ‘tourist attractions’ like Temenos in

Middlesbrough or Angel of the North in Gateshead as ‘spec-

tacular symbols of positivity’ in the hope of regenerating these

areas that were wilfully rundown under the Thatcher govern-

ment of the 1980s. So, the Tower became my focus. I decided

to walk around Blackpool and photograph the Tower at every

point that it became visible within a half-mile half-circle, the

Tower always the same size and in the same position in every

shot. I had a few things in mind: John Baldessari’s Aligning:

Balls (1972), the Situationist ideas of ‘dérive’ and ‘psychogeo-

graphy’ and Victor Burgin’s UK76 (1976) ... but ultimately, I

felt that I’d found a way to objectively photograph the misery

of Blackpool without having to focus on it or seek it out ... the

framing of the Tower always dictating the content of each im-

age. So, the framing of the Tower has this duality: it is at once

a study of this majestic tourist attraction, this arguably cynical

deployment of a super-structure, but also a way to objectively

photograph the sadness that surrounds it.

“Anish and Antony Take Afghanistan”: This work stems

from an idea that I had to make ‘sculptural transplants’ of

public artworks by Antony Gormley and Anish Kapoor to

Afghanistan. The idea was a fantasy - I imagined myself being

the head of a United Nations-commissioned ‘think-tank’ that

would donate existing public artworks from the UK to

Afghanistan. The idea being that if the work of these two

sculptors can be used to ‘regenerate’ poor areas like Gateshead,

Middlesbrough, Stratford et al, then surely it might help to re-

generate a poverty-stricken, war-torn and economically broken

country like Afghanistan. So, I had someone make me images

of huge public sculptures ‘transplanted’ into the vast planes of

Helmand Province; but it didn’t really work, it just looked too

trite, too easy and flippant. This lead to me think more about

the scenario of Anish and Antony being deployed by the UN to

‘save’ Afghanistan than the actual images of what they might

do there. So I invented this story, I imagined what might go

on behind the scenes and I thought that this could only really

work as a sort of graphic novel or cartoon.

I was very lucky to then work with an artist called Will Henry

- he took my sketches and words and turned them in to these

great images ... this very concise fantasy that is probably

nearer to reality than we’d like to imagine.

“A Balloon for Spandau”: This is part of an on-going series

of works that began with A Balloon for Britain (2012). In A

Balloon for Britain, I imagined myself (again) to be a gov-

ernment employed ‘think-tank’. I imagined that the current

Conservative government had offered me millions of pounds

to devise a scheme that would regenerate Britain’s 10 poorest

towns and cities. Now, obviously, the government are happy

to pay my think-tank several million pounds to come up with

a spectacular and highly visible ‘solution’ which demonstrates

that they care about these depressed and failing communities,

but they don’t really want to spend billions on building a new

infrastructure that involves creating manufacturing indus-

tries, hospitals, schools or social housing. Essentially, they

just want to ‘cheer up’ these places - they don’t want to deal

with the real problems, but they want to be seen to be doing

‘something’. With this as my brief, I came up with the idea

of floating gigantic (50 metre tall) party balloons across each

of these 10 poverty stricken cities ... and of course my idea

was a hit. The government got lots of positive press, and the

people enjoyed having enormous party balloons float over their

towns. My concept was so successful that I have since been

employed to create A Balloon For America (2013) - floating

balloons over the 10 poorest cities in the USA and A Balloon

For Sélestat (2013) - 10 balloons floated over a small and quite

nondescript town in France. So, having visited Spandau and

realising it was not so much poor as just a bit dull, I decided to

propose floating a balloon over the area near the train station

in the hope that I might bring both joy and ambition to the

people who live and work there. Early market research shows

that of the 100 people asked to express a ‘pro’ or ‘anti’ balloon

opinion, 67 people said they welcomed the idea, 29 thought it

was potentially hazardous to both motorists and aircraft and 4

people said they did not care either way.

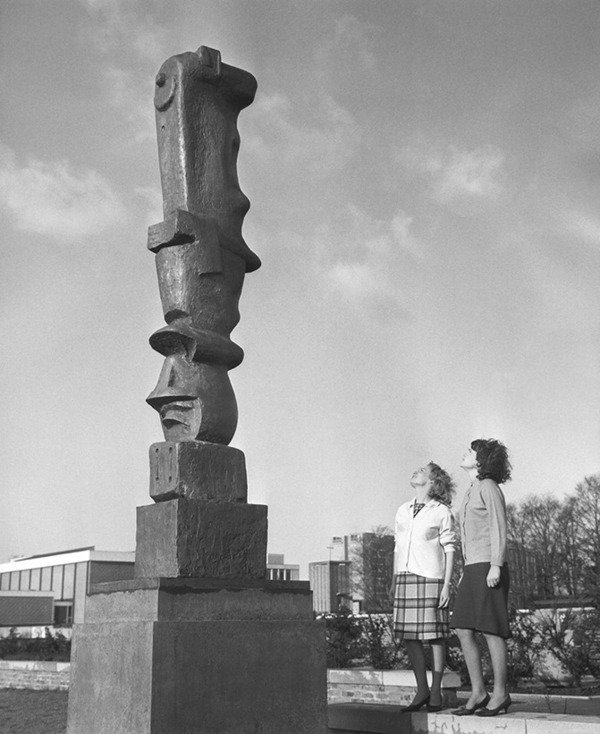

Finally, there is one more work - Totem Motif - from which the

show takes its title. This is a ‘found’ photograph from 1964. It

shows two young women admiring a recently erected Henry

Moore public sculpture in the ‘new town’ of Harlow, Essex.

Moore, like his progeny Kapoor and Gormley, was a master of

the banal public artwork.

Scott King was born in Goole, East Yorkshire, England, 1969.

He lives and works in London. In the 1990s he worked as

Art Director of i-D magazine and later as Creative Director

of Sleazenation magazine. As a graphic designer he has

collaborated with such iconic figures as Malcolm McLaren,

the Pet Shop Boys, Michael Clark and Suicide. King’s work

has been exhibited worldwide at such institutions as the

Museum of Modern Art, New York; Museum of Contemporary

Art, Chicago; Palais de Tokyo, Paris; The State Hermitage

Museum, St. Petersburg; the Institute of Contemporary Arts

and the Barbican, London.

On 10 and 11 July 2014, Scott King will curate ‘The Festival

of Stuff’ at Haus der Berliner Festpiele, Berlin.

Scott King is represented by Herald St, London and Bortolami,

New York.

Opening on May 16, 19 - 21 h

Between Bridges

Keithstrasse 15 - 10787 Berlin

Wednesday to Saturday 12 - 18 h