Sand-Ness

dal 10/12/2014 al 28/2/2015

Segnalato da

Yoav Hirsch

Halil Balabin

Aya Ben Ron

Irith Bloch

Avital Cnaani

Itzhak Danziger

Gilad Efrat

Shay Kocieru

Moshe Kupferman

Sigalit Landau

Karin Mendelovici

Tali Milstein

Benedetta Pedone

Yechiel Shemi

Assaf Shoshan

Erga Yaari

Liav Mizrahi

Laura Schwartz

10/12/2014

Sand-Ness

Contemporary by Golconda, Tel Aviv

The exhibition presents work by: Halil Balabin, Aya Ben Ron, Irith Bloch, Avital Cnaani, Itzhak Danziger, Gilad Efrat, Shay Kocieru, Moshe Kupferman , Sigalit Landau, Karin Mendelovici, Tali Milstein, Benedetta Pedone, Yechiel Shemi, Assaf Shoshan, Erga Yaari.

Sand- Ness

curated by Liav Mizrahi

“When persons are moved in blocks, they can be supervised by personnel whose chief activity is not guidance or periodic inspection (as in many employer-employee relations) but rather surveillance – a seeing to it that everyone does what he has been clearly told is required of him.”

Shay Kocieru shows four photographs of female prison guards in regular service. The subjects, in their late teens, are shown in full-body portraits with the detention center in the background. Nameless and unidentified, they seem at first sight schematic, dogmatic and devoid of personality. Only a close look reveals that everyday questions are being raised regarding the manner of their choice to be photographed. They each sport small elements that differentiate them from one another. One has a necklace with a medallion bearing her name, the other a diamond. One has groomed fingernails, a third chiseled eyebrows. Each of the subjects offers a minor option – hidden from view – to discover her personality. These works embody the tension between the totalitarian space in which the prison guards are situated, the fascistic relations between the photographer and the subject, the relations of the male prisoners to the young female wardens, and within it all, the longing for individuality. These photographs constitute the basic social arrangements according to which the participants, namely us, are constantly placed under a certain regularity and authority. Whether it is judiciary, as in the prison, or social – it shapes our appearance.

“A basic social arrangement in modern society is that the individual tends to sleep, play and work in different places, with different co-participants, under different authorities, and without an over-all rational plan. The central feature of total institutions can be described as a breakdown of the barriers ordinarily separating these three spheres of life.”

In 2010 Assaf Shoshan photographed Ta’aban, a refugee from South Sudan who spent three years in Israel with his family. Ta’aban, whose name in Arabic means “tired”, is photographed running in the Eilat mountains. Ta’aban’s status, which like that of many refugees remains undefined, since the state refuses to define them and grant them their rights as required by international law, has been translated by Shoshan into a moving image in which Ta’aban is seen running on the spot. What changes is the light, the time that runs out, the time that grows dark. Ta’aban’s place, his definition, remains fixed and unchanged. Only the movement of his hands as they wipe the sweat from his brow, only the striped robe that flutters on his body, which slowly turns into a black human silhouette. For several years Ta’aban remained without rights, until he returned with his family to South Sudan. Since then there has been no contact with him. In an artistic act Shoshan defines Ta’aban in the act of running, as an act of working. As an act of mediation between an agent (the artist) and a contract worker (Ta’aban). Shoshan paid Ta’aban some money for a day’s work, Ta’aban took on the task willingly – perhaps wishing to convey a message against his undefined status.

“Whether there is too much work or too little, the individual who was work-oriented on the outside tends to become demoralized by the work system of the total institution.”

Erga Yaari addresses the refugee’s situation in Israel from a slightly different perspective than Shoshan’s. In the film Great Shape Yaari presents the refugee as a transparent figure. The figure of the refugee as an invisible man who sees life passing him by, as only his situation never changes and remains repetitive. At this point Yaari’s approach seems similar to Shoshan’s. The film is shot with a mobile phone camera, depicting a dark-skinned migrant worker cleaning the sports equipment at a gym. He does not do it during off hours, but together with the people exercising, after them and following them. This point differs from Shoshan’s approach. While Shoshan leaves the subject of his film disconnected from daily life and focuses on his nomad existence, Yaari presents the refugee as trapped in an unregularized status in Israel and trying to make a living through a menial job that turns him into a modern slave, without identity or color. With a sarcastic manner and a unique angle Yaari manages to capture some grotesque situations that create a hybrid between the migrant worker and the exercisers. Shoshan’s approach is romantic, whereas Yaari’s is realistic and precise, showing the absurd situations in the refugees’ daily lives. The film is accompanied by a soundtrack in which a Sudanese woman reads out instructions for relaxation and physical exercise from YouTube.

Yaari’s film is in dialogue with voyeuristic films that can be found on the internet, and in that regard too it stands in opposition to the heroism of Shoshan’s film.

“The barrier that total institutions place between the inmate and the wider world marks the first curtailment of self.”

Avital Cnaani presents Border, from 2004. An iron sculpture painted deep blue whose dimensions simulate a police/military barrier that can be seen in demonstrations, checkpoints, entrances to restricted sites and so on. The sculpture translates the “furniture” of the Israeli public sphere into the space. Blocking the spatial movement in the gallery, blocking the landscape and the body. The blue color directly takes on a loaded local meaning. The blue of the flag becomes the blue that is in charge of territory in the gallery space. Border is a monumental, total and direct work. Cnaani’s work conducts a dialogue with the sculptures of Yechiel Shemi. The exhibition features 3 of Shemi’s drawings. Two untitled drawings from 1981 seem to depict sketches for sculptures. On small sheets of drawing paper, quadrilaterals and rectangles cut into the paper, creating a square within a square, a barrier followed by a barrier. Horizontal, vertical and diagonal lines crisscross the paper and are lined with dots, perhaps marking the welding points for the future sculpture. Shemi’s sculptures explore the obstruction of landscape and space, in a grandiose disruption that erupts like a rust stain against a blue sky. On the other hand, in nature, his sculptures come to resemble soft sheets of Plasticine and lines that merge into the features of the existing landscape. The third drawing is a sketch for a landscape sculpture intended for Mitzpe Ramon. An outdoors sculpture that stretches from the two ends of the wadi to create a bottlenecked passage. The unrealized sculpture looks like a sketch for the separation wall in Judea and Samaria, with an option for a gate and a checkpoint or, alternately, a breach in the wall.

“Inmates typically live in the institution and have restricted contact with the world outside the walls.”

Another artist of Shemi’s generation is Yitzhak Danziger. Danziger has four drawings in the exhibition. Two are automatic drawings, as a way to think the relationship between stone, metal and landscape sculpture and drawing as a medium in its own right in his oeuvre as a whole. These drawings feature “tearings” in indistinct shapes that demarcate the white space of the paper. His early drawings assimilate wandering around Palestine and its blurred borders during the Second World War. The drawing Mirror Enclosure (1971) joins his series of drawings and polished bronze sculptures that takes the grazing enclosures in the primordial land as a departure point. This work, with its circular composition comprised of a structure made of slices of mirror surfaces, shows Danziger starting to play the role of the artist as a mediator between man and environment. Danziger saw the artist’s role as a shaman who connects the social and the spiritual. The fourth drawing, which looks like a sketch for the famous Nimrod, is an exception. Here Nimrod resembles Michelangelo’s Rebellious Slave from 1513.

“The full meaning for the inmate of being ‘in’ or ‘on the inside’ does not exist apart from the special meaning to him of ‘getting out’ or ‘getting on the outside.’ In this sense, total institutions do not really look for cultural victory. They create and sustain a particular kind of tension between the home world and the institutional world and use this persistent tension as strategic leverage in the management of men.”

The prisoner named Pini, the artist Halil Balabin’s uncle, is seen in a projected photograph holding a rug he made during his imprisonment. In the background is the voice of Balabin’s mother, criticizing his uncle. Pini has been in prison in the USA for 35 years. He was charged with murder. Pini is a warning sign for proper behavior for his nephew Halil, who has grown up in his story’s shadow. The tiny room in the exhibition, resembling a dark solitary confinement cell, gives the viewer the sense of entering a documentary film without being able to see the film in its entirety. There is no such film, only the wait for release. The work, being shown for the second time after garnering praise last summer when it was first shown at the graduation show in Bezalel, Jerusalem, is exhibited together with several new works, including dolls that Balabin makes with his partner Merav Kamel. The ironic dolls look as if they were improvised from any available material as a hobby during imprisonment.

Gilad Efrat shows the painting Ansaar IX. This painting, part of a series, was painted following Roi Kuper’s 2003 photographs of Ktziot prison in the Negev, also called Ansaar, after a detention camp in Lebanon. This detention center is the biggest in Israel, and holds security, political and administrative prisoners as well as infiltrators. This painting displays modernist characteristics like the paintings of Piet Mondrian, who revealed the recurring pattern of natural elements translated into urban construction, that is, grid construction. These movements become an All Over composition of fences and watchtowers, strewn with the remains of barbed wire fences that look like snakes emerging from their nests in late summer. With only two colors and with automatic brushstrokes and an abstract painting approach, Efrat creates the habitat of a total institution, disciplining systems that collapse only to be rebuilt (Ktziot prison was closed for a while and then reopened).

“Although some roles can be re-established by the inmate if and when he returns to the world, it is plain that other losses are irrevocable and may be painfully experienced as such.”

Another painter who manages to convey the feeling of suffocation is Moshe Kupferman. In a large-scale oil painting, the older Kupferman’s painting maintains a dialogue with the younger Efrat’s painting. Here Kupferman’s work is crude, sharp, monumental, as if the painting controlled the artist during the making. Kupferman’s paintings are based on the grid, the lattice, the blocking lines. There is also an obsession with repressed memories that return and reemerge as a trapped and frenzied psychic state. These are only preliminary remarks on the paintings of Kupferman, who in his paintings dealt with construction and destruction and who is featured in the exhibition as a point that connects its two aspects. The physical prison that turns into a mental prison.

“With objects that can be used up – for example, pencils – the inmate may be required to return the remnants before obtaining a reissue”

Irit Bloch, born 1938, draws in wool. In the exhibition she shows a selection of drawings from the last years. For years Bloch has been making drawings and works on paper. She started with paintings that featured tearing and shredding and neurotic arrangements on paper, and went on to make tiny drawings of black surfaces that looked like thick hair or a tangled fence, consequently translating the drawings into automatic actions using thread. Bloch knits and sews miniature drawings in spectacular fashion, translating a complex psychic state resulting from loss. Precision, neatness and caution together with fear and anxiety are suggested by these drawings. Fascinating and astounding, it is hard to believe that they were made by a human hand. Her drawings, which also turn into tiny objects, show Bloch restraining herself from erupting. This tension can be felt mainly in her keeping to the work’s borders. Over four decades the format of the rectangle has been consistent in her work. Here too, as in Kupferman’s and Shemi’s work, Bloch explores blocking the space of the paper or the canvas. Blocking that is all about concealing, covering and blindness, while at the same time preserving a stable mental state, like walking in limbo, on the threshold of the inferno’s abyss.

“This sense of dead and heavy-hanging time probably explains the premium placed on what might be called removal activities, namely, voluntary unserious pursuits which are sufficiently engrossing and exciting to lift the participant out of himself, making him oblivious for the time being to his actual situation.”

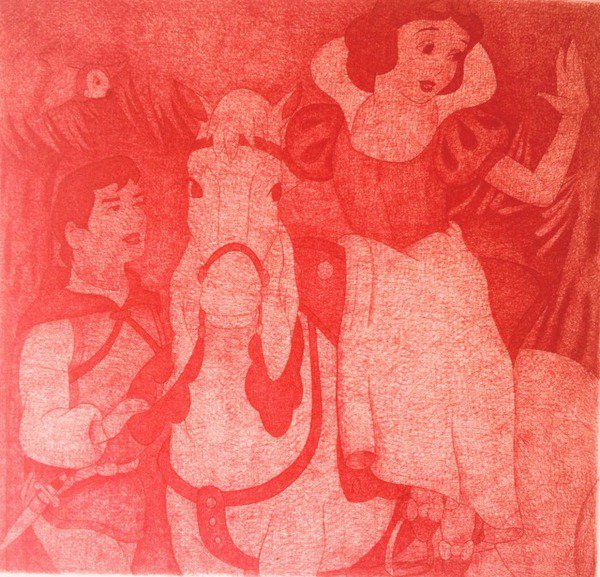

Autoratism and obsession are also embodied in Benedetta Pedone’s drawings. Her large works are made of Xs, drawn in red ballpoint pen and forming, X by X, images taken from Disney’s princess films. Pedone’s drawing scratches, etches and injures, as if repeatedly lashing the paper until it produces an utterly incongruous image, until it secretes the blood and sweat of the artist. These drawings create a paradox that belies the sweet image of a kissing princess and prince. A terrible passivity is revealed by the image, alongside an almost murderous activity with the discovery of the drawing action. The size of the work instils the exhibition with a nightmarish atmosphere. Snow White being led by the prince. In the Beginning, the work’s title, when the end in reality is different.

Pedone creates a disruption of the feminine fantasy, this sick fantasy that posits a submissive woman whose role is to wait for a man to come and rescue her. With thousands of red crosses she sets fire to the fantasy and turns it from a sweet dream into a nightmare.

In addition to the works on paper, Pedone draws a selection of her images directly on the walls. This action alludes to sketches made by inmates in prisons, from counting down their remaining time to creating wall paintings to decorate the prison cell.

“Some mental hospitals have the distinction of providing two quite different conversion possibilities – one for the new admission, who can see the light after an appropriate inner struggle and adopt the psychiatric view of himself”

Love as anxiety can also be found in the work of the painter Tali Milstein. The painting On Love and Anxiety or What is Between Them shows a couple lying down. The man is on his back and the woman is on top of him. For a moment she looks back at us, as if caught in the act that was stopped by us – the viewers, the voyeurs. But another look reveals that in fact she is photographing us, or perhaps the couple itself through a mirror. Love is “the heavenly Jerusalem”. Half of the picture, on the floor on which the couple is lying, reveals an image of Jerusalem, as if in an inverted mirror. A typical Jerusalem view, with the Dome of the Rock in the center. A landscape painted like an impressionistic painting, with dense brushstrokes. An upside-down Jerusalem, without a single stable piece of land, serving as the surface that carries a pair of lovers. Jerusalem of sin and pride. The Jerusalem syndrome, a hallucination, or a girl’s elegy on her boyfriend’s body, these are the thoughts that come to mind looking at this loaded painting.

“A margin of self-selected expressive behavior – whether of antagonism, affection, or unconcern – is one symbol of self-determination.”

Love and anxiety come up a third and fourth time in the work of Karin Mendelovici. A 7-minute video shows the figure of the artist standing in front of the camera, taking up most of the frame. She starts listing all the things she likes in the world: colors, foods, emotions, feelings and people. The video conveys with maximum precision the thin line between healthy humor and the insanity of horror vacui. Listing all the things in the world, from large to small, from essential to marginal, creates tension on the verge of trauma. The fear of losing something, the fear of not remembering and the fear of being sucked, despite the richness of everything, into an empty space.

“On admission to a total institution, however, the individual is likely to be stripped of his usual appearance and of the equipment and services by which he maintains it, thus suffering a personal defacement.”

Aya Ben Ron shows around half of a series of prints, combined with photography. The series Margalit (2007) depicts the house of Ben Ron’s grandmother, a gynecologist. The clinic was located in the grandmother’s house, there was no full separation between the private and the public space. The blurring of these two spaces creates great tension. Gynecology (a predominantly male profession), together with the woman’s place in the family (at home). An unease emerges in thinking about treating women at a private home – the home as a concept that conveys warmth and comfort becomes, through the introduction of the clinic, an unsterile and even abject space, in a sense even threatening. The prints are unpopulated apart from a fictional figure of a woman/flower added by the artist. Ben Ron recalls that her grandmother’s work space was not forbidden to play in, and the medical instruments and books became toys. On the one hand she played like any other girl playing with her grandmother’s things, but on the other there was something terrifying in it. It is one family’s aberration and perversion and another family’s norm, which ended up influencing Ben Ron’s fascinating work as a whole.

“In total institutions, exposure of one’s relationships can occur in even more drastic forms” (33)

Sigalit Landau concludes the list. The work Love is made of the heating element of a metal space heater. An intimate, personal heater, deigned to give a warm feeling. The radiated heat becomes a hallucination in the shape of the word LOVE, which is revealed as potentially dangerous, burning and scalding. Like a burn on the warming body, a princess’s dream, a sweet fantasy that turns from dream to horror

“I have defined total institutions denotatively by listing them and then have tried to suggest some of their common characteristics”

The exhibition Holot – Sand-ness is an exhibition about situations of human imprisonment. The physical and the mental prison. The name of the exhibition is taken from the name of the detention facility Holot, which was opened in December 2013. The facility was designed as a solution for the “problem” of refugees, infiltrators and asylum seekers in Israel. Since its establishment the facility has provoked opposition and a public debate about living conditions in it. The daily restrictions, the facility’s legality, the state’s refusal to define its inmates. In September 2014 the Supreme Court ruled that the facility was illegal and demanded that the state closed Holot within three months.

While the exhibition deals with the physical state of the imprisoned person, the breaking of his spirit, the restrictions on his body – its other aspect is a semantic meditation on the word “Holot”, which syntactically in Hebrew denotes a group of sick women. I have chosen to group together pieces by women whose work conducts a dialogue with the unstable edge imprisoned in the artist’s soul. Pieces that stretch the psychic and emotional boundary and its translation into a work of art. These works discuss an infinitely spiraling state of anxiety and existential tension similar to that of a prisoner.

Image: Benedetta Pedone At First, 2004 Ballpoint pen on paper 104x110 cm

Opening: Thu Dec 11 8pm

Contemporary by Golconda

117 Herzl Street

Mon - Thu 11am to 7pm

Fri 10am to 2pm

Sat 11am to 2pm