Philipp Furhofer

dal 29/4/2015 al 26/6/2015

Segnalato da

29/4/2015

Philipp Furhofer

Galerie Judin, Berlin

In Light of the Hidden. Like the subjuect matter they depict, Furhofer's creations are between two modes of being: they function as light boxes and as paintings.

The arresting art works in Philipp Fürhofer’s first exhibition for Galerie Judin: In Light of the Hidden, are multi-layered and entrancing. Like the subject matter they depict, Fürhofer’s creations are between two modes of being: they function as light boxes and as paintings. Depending on whether the light is turned on or off, the contents are illuminated or shrouded. In the pieces where the light rhythmically switches via a timer, we have to concentrate in order to absorb the information relayed in these alternating states. This game interferes with the more straightforward act of looking that we might employ when perusing a traditional painting. It casts us in an active role, one that encourages us to move around and adopt different positions of engagement.

If Fürhofer’s work is about the suspension between two states, then the phrase: ’between two worlds’ could have been coined for the artist himself. Torn between pursuing a career as an artist and as a pianist, Fürhofer decided on art, though music, and most notably opera, are still extremely important in his life and influential for his art practice. It was through his work for the stage, creating sets for some of the world’s greatest opera houses, that Fürhofer learnt how to captivate an audience, and it is Fürhofer’s awareness of the role of the viewer that puts him in such a unique position as an artist. Not only do we need to be active, rather than passive, when considering his practice, the spy-foil surfaces of Fürhofer’s works throw back our own reflection when the light is off, and banish us to invisibility when the light comes on. This forces us to look beyond our own image and into the interior of what the work contains. This is apparent when we consider What We Call Reality. With the light on, we find a throng of lively figures running and jumping, whereas with the light off, we find instead our own reflection amongst a tangle of wires, a viscous, bloody streak, and, where the figures were, smears of bleached-out, fleshy pink paint.

Besides evoking the transitoriness of life, What We Call Reality turns our thoughts to the corporeal. Fürhofer was inspired to create his multi-layered objects, with their neon lights, bulbs, rubber tubes and blend of organic and inorganic matter, after looking at x-rays of his own chest when he was lying in a Berlin hospital. The sense of dislocation between peering at an image of one’s own insides, while simultaneously presenting an integrated, apparently hermetically sealed physical vessel to the outside world, proved an unnerving, but inspiring paradox.

Tristan’s Body, a reference to Wagner’s opera ’Tristan und Isolde’, is unlit. The focus of this work is painting and its strange marriage to pieces of scrunched up plastic and other fragments of contemporary detritus. We see the outline of Tristan’s body, awash with rain and sea foam, and merging with this, a series of sails and ropes that allude to the set for the prelude of Act One, on the deck of Tristan’s ship during the crossing from Ireland to Cornwall.

The power of nature, and particularly the sea, is a constant throughout the exhibition, a metaphor for the uncontrollable forces and relentless rhythms that shape our lives and loves. Fürhofer’s decision to turn to ’Tristan und Isolde’, one of the pinnacles of the operatic repertoire, as inspiration for a number of works for this show, leads us to question what he is communicating to us. We know that for the protagonists of this tragic story, night must not give way to day, for not only will this mean physical separation for the two lovers, it will also lead them to conclude that the only recourse open to them is to die, rather than be separated. Paradoxically, it is through dying that they preserve their love and its story for ever, and in so doing, outwit death. In his essay, ’Is Wagner Bad For Us’, Nicholas Spice comments: ’The second act of Tristan und Isolde is Romanticism’s greatest hymn to the night, not for the elfin charm and ethereal chiaroscuro of moonbeams and starlight ... but night as a close bosom-friend of oblivion, a simulacrum of eternity, and a place to play dead … a zone beyond time’.

The notion of creating a simulacrum of eternity, albeit a fleeting glimpse, is a leitmotif that pervades Fürhofer’s works. Seduction divides into four parts, each of which is illuminated on a timer. As a whole, it resembles a fathomless under-water world with tumbling light bulbs – actual and painted – and cut-outs of androgynous, faceless figures. An inversion of what Guy Debord described as ’The Society of the Spectacle’ (where ’all that once was directly lived has become mere representation.’), instead of adding another layer to our consumerist cake and inauthentic engagement with surface and society, it shocks us into a visceral reaction, provoking us with the unexpected: wires wriggle like jelly fish tentacles, and the depth of the abyss is impossible to gage. It is spectacular and, as its title suggests, thrilling as well as disturbing.

There is a strongly spiritual quality to Fürhofer’s tactile creations. Their evocative nature prompts us to slip between temporal and spiritual planes and reach for a higher order inspired by beauty, art and music. The diptych Paying Homage has a grandeur that is born of its connection to an opulent stage set. With pink spy foil on the left, and blue on the right, framed by billowing sails, there in the centre, crossing the divide, is a Gargantuan, ghostly figure, studded with wires or tentacles, and glistening light bulbs. We could interpret this source of energy as a God-like figure, or the personification of a life-giving force, but its strangely obscure form also hints at the underworld, suggesting that while it might give life, it could also take it.

At the core of Fürhofer’s practice is a deep awareness of the fragility of human existence and the interface between the spark of life and the shadowland that waits in the wings. There is a strange poetry inherent in the everyday that mourns our inevitable demise. It is there even in the detritus that spills over into our lives, and Fürhofer is adept at capturing this. Kiosk resembles a phone booth. Bottles, billboards and packaging flash up for a matter of seconds only to disappear and be replaced by the reflective spy foil that reveals shadowy figures, wires and drips of paint.

As its title suggests, Bending Light reveals complex prisms and kaleidoscopic spaces forged from mirrors and fluorescent tubes. It conveys an eerie sense of suspension in a place not attached to the physical, and again we return to the simulacrum of the eternal. In contrast, Becoming Matter with its underwater, blue-lit bubbles and the outline of life-giving hands, suggests the beginning of time, of man, of everything, and a return to the sea in an endless cycle.

Jane Neal

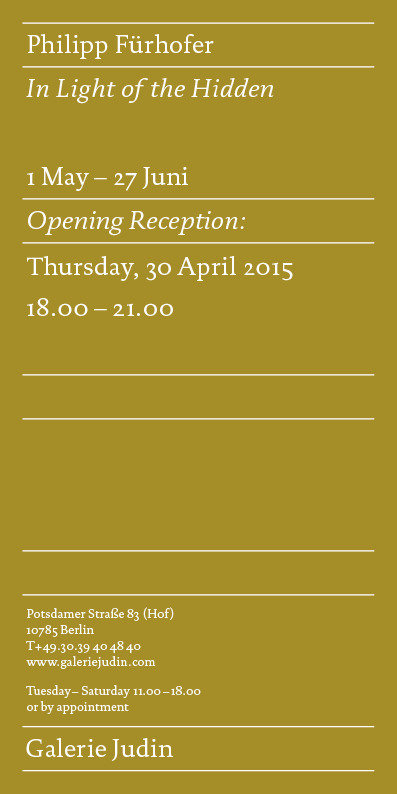

Image: invitation

Opening: 30 April 2015

Galerie Judin

Potsdamer Strasse 83

Berlin