Basquiat

dal 10/3/2005 al 5/6/2005

Segnalato da

10/3/2005

Basquiat

Brooklyn Museum of Art, New York

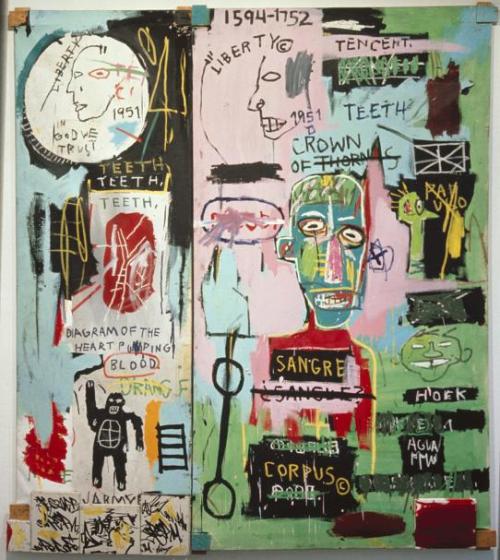

This exhibition gathers together more than one hundred of Jean-Michel Basquiat's works. It is organized chronologically, with special sections highlighting Basquiat's interest in music, language, and Afro-Caribbean imagery, along with his use of techniques such as collage and silkscreen. Throughout his career he often chose to paint on rough, handmade supports and intentionally pursued the awkward look of outsider art.

Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960–1988) was born and raised in Brooklyn, the son of a Haitian-American father and a Puerto Rican–American mother. At an early age, he showed a precocious talent for drawing, and his mother enrolled him as a Junior Member of the Brooklyn Museum when he was six. Basquiat first gained notoriety as a teenage graffiti poet and musician. By 1981, at the age of twenty, he had turned from spraying graffiti on the walls of buildings in Lower Manhattan to selling paintings in SoHo galleries, rapidly becoming one of the most accomplished artists of his generation. Astute collectors began buying his art, and his gallery shows sold out. Critics noted the originality of his work, its emotional depth, unique iconography, and formal strengths in color, composition, and drawing. By 1985, he was featured on the cover of The New York Times Magazine as the epitome of the hot, young artist in a booming market. Tragically, Basquiat began using heroin and died of a drug overdose when he was just twenty-seven years old.

This exhibition gathers together more than one hundred of Jean-Michel Basquiat's finest works, including many that have never been shown in the United States. It is organized chronologically, with special sections highlighting Basquiat's interest in music, language, and Afro-Caribbean imagery, along with his use of techniques such as collage and silkscreen.

The exhibition seeks to demonstrate not only that Basquiat was a key figure in the 1980s, but also that his artistic accomplishments have significance for twentieth-century art as a whole. Basquiat was the last major painter in an idiom that had begun decades earlier in Europe with the imitation of African art by modern artists such as Picasso and Matisse. Inspired by his own heritage, Basquiat both contributed to and transcended the African-influenced modernist idiom.

Basquiat once told an interviewer, "Since I was seventeen, I thought I might be a star." As a teenager, he plunged into the emerging eighties art scene. He met artists and celebrities at the Mudd Club; appeared on Glenn O’Brien’s TV Party, a television show about the downtown scene; and starred in a low-budget film, Downtown 81 (New York Beat), based on his own life. All the time, he was also making art: hitting downtown Manhattan buildings with spray-painted aphorisms, selling hand-painted T-shirts and collages on the streets, and making drawings. His big break came in 1980, when critics singled out his work at the Times Square Show, an exhibition showcasing young New York artists. He finally got a studio in 1981, when his first New York dealer, Annina Nosei, invited him to paint in the basement of her gallery.

Until then, he had little money to buy supplies, so he painted on window frames, cabinet doors, even football helmets—whatever he could find. After Basquiat began to make money, the quality of his art materials improved. Even so, throughout his career he often chose to paint on rough, handmade supports and intentionally pursued the awkward look of outsider art.

Basquiat started his career as a graffiti writer, signing his work SAMO© (for "same old, same old" or "same old shit"). But while his contemporaries sprayed colorful pictorial symbols and tags all over New York, the teenaged Basquiat addressed the public in enigmatic sentences sprayed in a plain script, such as "SAMO© AS AN END TO MINDWASH RELIGION, NOWHERE POLITICS, AND BOGUS PHILOSOPHY" and "PLUSH SAFE HE THINK / SAMO©." As a professional visual artist, Basquiat made language an increasingly important feature of his work. In some cases, words fill the entire canvas, leaving no room for images.

Basquiat used words to elaborate his themes, adding layers of verbal complication to his pictorial ideas. Sometimes, following a Surrealist or stream-of-consciousness technique, he built up running lists or diagrams of related thoughts. Often, he repeated the same words over and over again, achieving an almost hypnotic effect.

Basquiat’s words also serve a more strictly compositional function, playing a key role in the graphic construction of a painting. He was not the only artist using words in paintings during the 1980s, but he was perhaps the most successful at integrating text and picture into a dynamic whole. In Basquiat’s works, there is an especially harmonious affinity among written, drawn, and painted marks that have all clearly been made by the same hand.

Image: In Italian, 1983. Acrylic, oil paintstick, and marker on canvas mounted on wood supports, two panels. The Stephanie and Peter Brant Foundation, Greenwich, Connecticut

Brooklyn Museum

200 Eastern Parkway

Brooklyn, NY 11238

Museum Hours

Sunday 11 a.m. – 6 p.m.

Monday and Tuesday Closed

Wednesday – Friday 10 a.m. – 5 p.m.

Saturday 11 a.m. – 6 p.m.

First Saturday of Each Month 11 a.m. – 11 p.m