Italia Nova

dal 4/4/2006 al 2/7/2006

Segnalato da

Umberto Boccioni

Giacomo Balla

Carlo Carra'

Luigi Russolo

Gino Severini

Fortunato Depero

Enrico Prampolini

Giorgio de Chirico

Giorgio Morandi

Mario Sironi

Alberto Burri

Felice Casorati

Massimo Campigli

Alberto Savinio

Antonio Donghi

Arturo Martini

Piero Manzoni

Pier Giovanni Castagnoli

Maria Vittoria Clarelli

Guy Cogeval

Alessandra Mottola Molfino

Ester Coen

Flavio Fergonzi

Daniela Fonti

Mercedes Garberi

Claudia Gian Ferrari

Maria Stella Margozzi

Paolo Rusconi

Nico Stringa

Livia Velani

Pia Vivarelli

4/4/2006

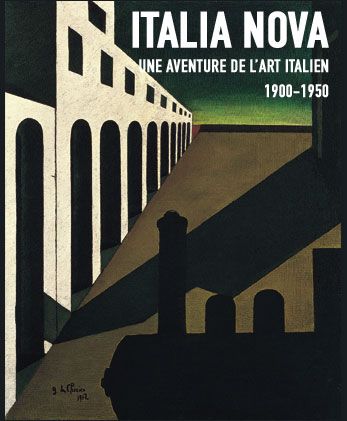

Italia Nova

Galeries nationales du Grand Palais, Paris

Une aventure de l'art italien, 1900-1950

Une aventure de l’art italien, 1900-1950

The exhibition opens with Balla’s 1904 painting, Elisa on the Door: the young woman invites us to step into the new century. The modern nature of this work with its daring photographic cut-outs already outstrips the Realism and Symbolism which dominated the arts in Italy in the late 19th century. In the same room, a 1909 painting by Boccioni, Workshops at Porta Romana, reveals a new spirit, a few months before the Futurist theories (The Manifesto of Futurist Painters dates from 11th of February 1910) and sums up the aspirations of the new generation of Italian painters. They wanted to break with the pictorial tradition of the late 19th century and to promote modernity, understood primarily as change and innovation.

Futurism

A rigorous selection of paintings gives a complete panorama of the Futurist movement from its beginnings to the 1920s. The Manifesto of Futurism by the writer and poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (1876-1944) was published on the front page of Le Figaro in Paris in 1909 attracting the support of many artists, in particular Umberto Boccioni (1882-1916), Giacomo Balla (1871-1958), Carlo Carra' (1881-1966), Luigi Russolo (1885-1947) and Gino Severini (1883-1966). After the premature death of Boccioni, who was the movement's leading theorist for the plastic arts, Balla, Fortunato Depero (1892-1960) - who worked for Diaghilev's Russian Ballet - and Enrico Prampolini (1894-1956) carried on the dream of the Futurist Reconstruction of the Universe.

More than an art movement in the strict sense of the term, Futurism was an overall aesthetic, almost a lifestyle and the symbol of modern Italy. It touched on all the arts, painting, sculpture, architecture, design, graphic arts and fashion, combining them in a vision of the total art work, and paying particular attention to the analysis and re-creation of movement, the dynamics of volume, speed and propulsion.

Concentrating on Italian painting and sculpture during the first half of the 20th century, Italia Nova invites visitors to discover or rediscover a whole section of European art from this period which is still little known in France. The exhibition is well timed, coming after Melancholy. Genius and Madness in the West, which included two works by de Chirico and one by Sironi, and during the celebration of the centenary of the death of Cezanne, who was so important to many artists in the Italian avant-garde movements (de Chirico and Morandi in particular).

Some hundred and twenty works highlight the most significant Italian artistic movements: Futurism, Metaphysical Painting, Magical Realism and the Novecento movement, as well as the most conceptual works of the 50s. Alongside famous works by de Chirico, Morandi, Fontana or Burri are paintings and sculptures of artists much less often exhibited in France: Balla, Boccioni, Carra', Casorati, Campigli, Depero, Martini, Prampolini, Severini, Sironi, Savinio, ... and special homage is paid to Morandi.

Italy played an eminent role in European art in the first half of the 20th century, through the innovative character of Futurism, but also through its utterly original contribution to the rediscovery of "classical measure" which occurred almost everywhere in Europe after the experiments of the first historical avant-garde movements. The exhibition compares and questions the two extremes of artistic research in Italy at the time: on the one hand, the rejection of tradition by the Futurists; on the other hand, the return to certain classical forms.

In the opening months of 1911, Giorgio de Chirico (1888-1978) painted a melancholic self-portrait, Et quid amabo nisi quod aenigma est? The time he spent in Paris between 1911 and 1915 with his brother Alberto Savinio (1891-1952) brought him in contact with international art circles. De Chirico was encouraged by Apollinaire and the art dealer and collector Paul Guillaume, who organised an exhibition of his works at the Vieux-Colombier, - and it was in Paris that he painted some of his masterpieces such as La Matine'e angoissante in 1912 (the painting belonged to Paul Guillaume) and The Poet’s Enemy in 1914. De Chirico’s Metaphysical painting sought to reveal the hidden face of things, "When they are surprised in their mysterious solitude and strangeness". When they returned in Italy in 1916 because of the war, de Chirico and Savinio - with Carra', Filippo de Pisis (1896-1956) and the young Giorgio Morandi (1890-1964) - developed metaphysical poetics, which it each interpreted in his own language.

Classical Measure: Magical Realism and the Novecento Movement

The transition from Metaphysical painting to Magical Realism was easy, even if the tragic melancholy of de Chirico's paintings was tempered in the enchanted mood of the work of Felice Casorati (1883-1963), Antonio Donghi (1897-1963) or Severini. Although Carra'’s astonishing painting, Lot’s Daughter (1919), heralded the rediscovery of the values of the Italian primitives, Giotto and Paolo Uccello in particular, the trail had been blazed in 1916 by Severini's painting Motherhood which marked the first return to the classical order in European painting.

The years that followed saw several such "returns to order" in Italy, some founded on the values of authenticity - this was the case for Magical Realism and the rediscovery of Etruscan archaism in Massimo Campigli’s work (1895-1971) - while others, on the contrary, were more ambiguous, such as the Novecento movement championed by the critic Margherita Sarfatti. The Novecento was at first really attached to a return to classical traditions, in phase with a sensibility widespread in Europe at the time, but ended up in the 1930s defending the "eternal values" imposed by the political regime, whether in the representation of national identity, the defence of the family or the search for origins and the glorification of ancient Rome.

However some artists managed to avoid the pitfalls of damnatio memoriae as is shown by the tragic, monumental Expressionism of some large mural paintings by Mario Sironi (1885-1961) and the plastic power of sculptures by Arturo Martini (1889-1947) such as Nude Swimming Underwater, one of the masterpieces of Italian statuary between the wars.

Homage to Giorgio Morandi, a Solitary Artist

The exhibition pays particular homage to Morandi with a group of ten still lives. Although this painter was first inspired by de Chirico's ideas, he soon gave a very personal interpretation of the formal "suspension" inherited from the Metafisica. An independent artist, staying away from the art movements of the Fascist era, he concentrated almost solely on humble everyday objects, vases, bottles, cups and boxes made monumental by his remarkable economy of means, whether in colour or composition. Despite his isolation, Morandi remained close to the aspirations of European art of his time without being drawn into specifically Italian currents.

Tabula rasa

The exhibition ends with a small section called Tabula rasa (Clean Slate), which looks at the break made by several Italian artists immediately after the war, Lucio Fontana (1899-1968), Alberto Burri (1915-1995) and Piero Manzoni (1933-1963), and heralds a new great period in Italian art.

Produced jointly by the Re'union des muse'es nationaux and the MART (Museo di Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto) under the direction of Gabriella Belli, director of MART, the exhibition will be presented at the Galeries nationales du Grand Palais, Paris, from 5 April to 3 July 2006. The international advisory committee for the exhibition includes Pier Giovanni Castagnoli, Maria Vittoria Clarelli, Guy Cogeval, Alessandra Mottola Molfino, Ester Coen, Flavio Fergonzi, Daniela Fonti, Mercedes Garberi, Claudia Gian Ferrari, Maria Stella Margozzi, Paolo Rusconi, Nico Stringa, Livia Velani and Pia Vivarelli.

Media partners: Le Figaroscope, France Inter, and LCI.

Galeries nationales du Grand Palais

3, avenue du Ge'ne'ral-Eisenhower 75008 Paris

Hours:

Open every day, except Tuesdays, from 10 a.m. to 8 p.m., Wednesdays from 10 a.m. to 10 p.m. (Ticket office closes 15 minutes before closing time)

Admission:

Open all day.

without bookings: full price € 10, concession € 8

with bookings: full price € 11.30; concession price, € 9.30.

unlimited access with the Se'same card.