9/5/2007

Joe Bradley and Sarah Braman

Dicksmith, London

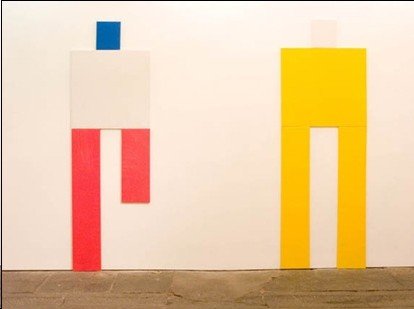

Joe Bradley paints still figures stranded outside time. Sarah Braman builds crystal shacks from the margins of the built environment. Their paintings and sculptures are constructed from found shards of wood and plastic, paint and slack canvas.

Shacks

Monsters are portents of the evolving future , mearcstappa , hybrids: centaurs and sphinxes, projections of the anomalous. As Dracula and Frankenstein were commentaries on disturbing aspects of their respective societies, so update to the glowing green of the Frankenstein monster-like The Hulk and the Draculean hemophage Ultraviolet, then step up to Joe Bradley stiffs and Sarah Braman shacks.

Joe Bradley paints still figures stranded outside time. Sarah Braman builds crystal shacks from the margins of the built environment. Their paintings and sculptures are constructed from found shards of wood and plastic, paint and slack canvas. Bradley forms recall the geometry of early modernist architecture, boats, sails and the triangulation of vector navigation. Braman forms also recall architecture, and upended broken furniture, shacks and crystals. The work is not small enough to be labeled as bject yet not as large as onument Theirs is the size of he thing a hybrid of monument and object partaking of both the private world of toys and the social space of architecture.

American proto-minimalist Tony Smith famously claimed that his sculpture Die, 1962, a six foot square welded steel box, was necessarily 6 feet high because to make it any larger would make it a monument and that to make it any smaller would make it an object. He took one average human measure, height, and extended it in three directions. In the 20th c. Vladimir Tatlin and Robert Smithson attempted to redefine the monument just as Marcel Duchamp and Andy Warhol attempted to redefine the object. Yet monuments still tend to be memorial art, presented as spare change in front of public buildings, and object art tends to be bound up in impenetrable personal mythologies. The one is entirely too public and the other entirely too private.

Smith claimed an average human height (and width, with arms extended) as the correct scale for sculpture and he was right about this. The median size is always right because it is the size of most things. But for all Smith rightness, there is a material contradiction within his scale. Steel is a very heavy and hard material that evokes monumental architectural construction, the hulls of ships and the armour of tanks. No matter what its size, steel is a sure sign of the enduring and the memorial. Due to its ubiquity, its near invisibility as material, steel was the preferred material of high modernist abstract sculpture. But steel is not a sign of the human scale.

Braman and Bradley work has the integrity of common materials that are imperative to an art made on the human scale. The median size of he thingis a size that empowers the common materials that make up ordinary things. These things are made in the way that most things are made, constructed through the economy of means necessary to the process of manufacture. Consider Tony Smith own hastily constructed full scale plywood maquettes, weatherproofed with black automobile undercoating. As a relatively cheap material, plywood was then in the same category as cardboard and plaster. As a secondary or provisional material it was a sign for the prototype.

The scale, the material and the direct construction locates the work of Bradley and Braman in an anachronistic but clear relationship to seminal works of early modernism. The original works of early modernist sculpture are likewise relatively small in scale, and often fragilely constructed of scrap material. The maquette is the paradigm of early modern sculpture. This fact is obscured by the over presentation of museum replicas and larger scale reconstructions. As examples, consider here Raymond Duchamp-Villon small scale plaster for Portrait of Professor Gosset, 1918. Contrast it to the slick large scale bronze version of the same in the Albright-Knox Art Gallery that was completed after his death. Consider Giacomo Balla original cardboard sculpture of Lines of Force in Boccioni Fist rather than the professionally painted steel museum replica on display in the Hirshhorne Museum and look at Pablo Picasso messy little scrap sheet metal Guitar of 1912 instead of Sir Anthony Caro painted steel garden follies. Kasimir Malevich Architectons were maquettes of this experimental type, not so much proposals for actual buildings as proposals of architectural principles. The fragile joinery of Braman sculpture and the slack canvases of Bradley also suggest a seeming rush to get the thing done. This hurriedness recalls the provisional plasters (and then the white painted bronzes) of Alberto Giacometti. It is a sign of urgency, of desire to see he thing

Bradley work is figurative and geometric; the body as a mechanical stiff of colored shadows cast by the light of Malevich Architectons as channeled through Minimalism. It is architecture as something that is done to us rather than by us. Bradley slack canvases are sails without the taut bluster of a storyline. They are paint and canvas once again and authentically as paint and canvas. Bradley images recall the early Constructivism of the sailor Vladimir Tatlin and the neo-futurist fantasies of the current Moscow painter Pavel Pepperstein. They recall the minimalist time machines of John McCracken and the neo-Ultraist speculations on the form of time by Robert Smithson. They have the nertia or invincible idleness that stops trains, jets and ships and transforms them into signs or symbols . They could be plans for sculpture.

As Bradley paintings are ships stranded with slack canvas so Sarah Braman's sculpture resembles detritus from wreckage: huts built of flotsam and jetsam. Braman constructions are built from anything but not everything. They barely, and therefore sharply, embody discrimination and choice. Her materials; upended tents and broken furniture, shards of Plexiglas, wood and other found materials, are not piled atop one another into a careless sculptural narrative but are attentively joined, edges layered in fragile seams. One does not so much gaze at these works as one glimpses a multiplicity of refractory views, and is seduced . These are crystalline shacks.

The crystal is now used by sociologists to represent the complexity of viewpoints on any social phenomenon, as opposed to the single point of view of the gaze. In art over the last century the crystalline metaphor began with he Sign, a large transparent crystal of quartz ceremoniously unveiled at the Darmstadt Artists Colony in 1901as an emblem of the new age . The crystal is a metaphor of illumination and confused with glass (Joseph Paxton Crystal Palace, 1851). In his 1919 Bauhaus manifesto, Walter Gropius wrote of "he structure of the futurerchitecture and sculpture and painting in one unity(rising) toward heaven from the hands of a million workers like the crystal symbol of a new faith." Understand the crystalline history of glass and steel architecture from Bruno Taut to Philip Johnson. The 20th c. architectural canon is constructed from the crystalline buildings of Behrens, Rietveld, Gropius, Tange, Johnson, Venturi, and Gehry among others. But the crystal shacks were made by the painters and the sculptors. A shack is a small crudely built cabin or shanty, often constructed from salvaged materials. It is the architectural equivalent to the early modernist conception of the maquette as a sketch model or proposal. Numerous seminal works of modernism were shacks. Tatlin original 1920 model for a Monument to the Third International was a shack, as were Kurt Shwittersvarious versions of the Merzbau. And Joe Bradley paintings are shacks and Sarah Braman sculptures are shacks. The shack is the first and the last construction , both primitive hut and modern proposal, and a monster outside of time.

Robin Peck, 2007

Dicksmith

74 Buttesland Street - London

Admission free