Foto

dal 9/6/2007 al 2/9/2007

Segnalato da

Laszlo Moholy-Nagy

Hannah Hoch

Josef Sudek

Rudolf Balogh

Jerzy Janisch

August Sander

Lotte Jacobi

Martin Munkacsi

Andre Kertesz

Matthew S. Witkovsky

9/6/2007

Foto

National Gallery of Art, Washington

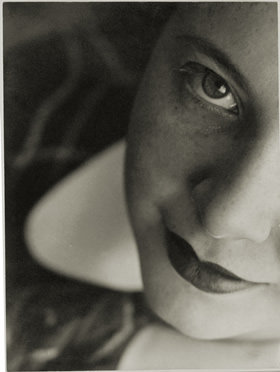

Modernity in Central Europe, 1918-1945: the story of photography's extraordinary success and popularity in Austria, Czechoslovakia, Germany, Hungary, and Poland during a time of tremendous social and political upheaval. The exhibition includes more than 150 photographs, books, and illustrated magazines from several dozen American and international collections. The show places famous talents, including Hungarian-born Bauhaus professor Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, German dadaist Hannah Hoch, and Czech artist Josef Sudek, in the company of one hundred exemplary but largely lesser-known individuals.

Modernity in Central Europe, 1918-1945

curated by by Matthew S. Witkovsky

The story of photography’s extraordinary success and popularity in Austria, Czechoslovakia, Germany, Hungary, and Poland during a time of tremendous social and political upheaval, is presented in Foto: Modernity in Central Europe, 1918–1945, the first survey exhibition devoted exclusively to this phenomenon. Premiering at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, June 10 through September 3, 2007, the exhibition includes more than 150 photographs, books, and illustrated magazines from several dozen American and international collections, among them many on view in the United States for the first time.

The exhibition is organized by the National Gallery of Art, Washington. Foto will travel to the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York (October 5, 2007 – January 2, 2008); the Milwaukee Art Museum (February 9 – May 4, 2008); and the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh (June 7 – August 31, 2008).

Foto places famous talents, including Hungarian-born Bauhaus professor László Moholy-Nagy, German dadaist Hannah Höch, and Czech artist Josef Sudek, in the company of one hundred exemplary but largely lesser-known individuals from this golden age of photography and birthplace of photographic theory. In this region, photography inspired the imagination of hundreds of progressive artists, provided a creative outlet for thousands of dedicated amateurs, and became a symbol of modernity for millions through its use in magazines, newspapers, advertising, and books.

“To recover the crucial role played by photography in the region, and in so doing delineate a central European model of modernity, is the double aim of Foto: Modernity in Central Europe, 1918–1945,” said Earl A. Powell III, director, National Gallery of Art. “Profound thanks go to the Central Bank of Hungary, the Trellis Fund, and to the many public and private supporters and lenders who made this exhibition possible.”

Exhibition Support

Sponsored by the Central Bank of Hungary. The exhibition is made possible by the generous support of the Trellis Fund. Additional support has been provided by the Trust for Mutual Understanding, the Marlene Nathan Meyerson Family Foundation, and The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, Inc. The exhibition catalogue is published with the assistance of The Getty Foundation.

Foto is divided into eight thematic sections, each of which brings together work from across central Europe to compare local differences against a heritage of shared institutions and attitudes towards modernity.

The Cut-and-Paste World: Recovering from War

Photomontage was pioneered as a technique for radical art in central Europe in early 1919, and it flourished there through the end of World War II. The artists of German Dada, such as John Heartfield, Max Ernst, and Hannah Höch, responded through photomontage to the mechanization and fragmentation of bodies during World War I, as seen in Heartfield’s Fathers and Sons (1924). In areas where WWI broke apart vast empires and brought hope to its constituent populations, particularly in Poland and Czechoslovakia, photomontage reflected a widespread optimism, seen in Jindřich Štyrský’s Souvenir (1924).

Laboratories and Classrooms

One highly influential legacy of modernist photography in central Europe is darkroom experimentation, for instance the play of abstract shadows in Jaromír Funke’s series Abstract Photo (1927–1929). For theorists and practitioners such as László Moholy-Nagy, Franz Roh, and Karel Teige, experimental camera work represented truly modern photography. Innovative methods were taught in art schools from Dessau to Lviv, Prague, and Bratislava, and the works were shown in large didactic exhibitions mounted in cities across the region, helping to broaden the acceptance of modernity.

Modern Living

Scenes of urban bustle or new construction, frequently taken from unusual angles or in extreme close-up, typify a modern style of image-making that became popular around 1930—a style embodied by László Moholy-Nagy’s iconic Berlin Radio Tower (1928). The exploding image world popularized modernity in a region filled with anxieties over such sudden and massive changes. Out of this “photomania” came many of the great talents represented in the international illustrated press: Life magazine and the Parisian tabloid Vu are unthinkable without Martin Munkacsi and André Kertész, both of whom got their start in Hungary.

New Women—New Men

The neue Frau or New Woman was a subject of intense public debate that was not only reflected in but also shaped by photography: pictures of female athletes and dancers, or new genres for the illustrated press such as the “photo essay” pioneered by studio photographer Yva (Else Neuländer-Simon). Male portraits by Lucia Moholy, Trude Fleischmann, and Éva Besnyő give their subjects a distinctly effeminate look, while others by August Sander or Lotte Jacobi capture the “androgyny chic” of certain German cultural circles, as seen in Jacobi’s Klaus and Erika Mann (c. 1928–1932).

The Spread of Surrealism

Surrealism has long been thought of mainly as a French phenomenon, yet a tremendous surrealist output, particularly in photography, originated in central Europe. Artists in Czechoslovakia and Poland expanded on surrealism’s concepts, even in provincial towns such as Olomouc or Lviv, home to the groups f5 (Czech, 1933–1938) and Artes (Polish, 1929–1936), respectively. These artists pursued a variety of image-making methods, from pseudo-documentary to happenings staged for the camera and fantastic self-portraits or photomontages, as seen in Jerzy Janisch’s Sisters (c. 1933).

Activist Documents

Given the pioneering development of photojournalism and the photo-illustrated press, as well as a broad culture of political dissent, it is not surprising that many photographers across central Europe turned to reportage in the later 1920s and 1930s. Germany is the country best known for political activism in photography, but Austria, Slovakia, and Hungary established strong activist groups, and Prague hosted the greatest international exhibitions of worker or social photography in the world at that time.

Land without a Name

Surprising as it seems picturesque landscapes and traditional scenes—such as Rudolf Balogh’s Shepherd with His Dogs (c. 1930)—captivated imaginations more than metropolitan views in this still overwhelmingly rural and ethnically varied part of Europe. Homeland Photography became a named movement throughout the region and received steady support from the press, the government, and the amateur photography network. “Naming” the land took on a heavy symbolic charge in the 1930s, as the Third Reich made land-grabbing the principal goal of its foreign policy.

The Cut-and-Paste World: War Returns

Just as World War I shifted central European modernism onto a new plane, World War II brought that modernism to a perverse and tragic conclusion. During WWII, some artists continued to use photomontage in private. Among them were Karel Teige, leader of the Czech avant-garde, who made hundreds of works for intended himself and his closest friends, and his compatriot Jindřich Heisler, who created his photomontages while hiding for more than three years to escape deportation. For these artists and others, the political ramifications of surrealism gained primary importance, as did the potential of photomontage to comment on the state of the world—a potential fully realized in these depictions of modernity in its twilight years.

National Gallery of Art

6th Street and Constitution Avenue - Washington

Open Monday through Saturday from 10:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. and Sunday from 11:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m.