Two exhibitions

dal 23/5/2008 al 20/6/2008

Segnalato da

23/5/2008

Two exhibitions

Yvon Lambert, Paris

One of the guiding principles of Bethan Huws' art is that it frequently utilizes given or found material. Each work develops in response to an actual set of circumstances: a place, or a situation, or a memory, or something read. In Pavel Braila' exhibition the word "want", is outlined 10 times in red neon. It will light up in 10 steps from the center to the edge, each step increasing the size of the word and the amplitude of its meaning.

Bethan Huws

Yvon Lambert, Paris, is pleased to announce the first solo exhibition of Bethan Huws in

France from May 24th until June 21st 2008.

Bethan Huws is born in 1961 in North Wales, she now lives and works in Paris.

Huws’art contains two main thoughts: disapproval of art that is predominantly visual and the

aim to make work that would focus on the gap between art and the common affairs and

concerns of people.

One of the guiding principles of Huws’art is that it frequently utilizes given or found material.

Each work develops in response to an actual set of circumstances: a place, or a situation, or

a memory, or something read.

Her art is very attentive to nuances of voice, tonal modulation and to the other expressive

modalities of language, as well as to the contingency of meaning on context, to the difference

between speech and writing, and, ultimately, to all that constitutes us as individuals.

Watercolours

Generally, throughout her career, Bethan has made watercolour drawings. In virtually all of

the watercolours the figures are suspended in a blank field; the colour is dilute; and the

figures are finely described yet equally schematic. The overall effect is of dual concreteness

and abstractness. The spatial implication of the drawings is crucial to their being, to their

coming into being and to their consistency.

Word Vitrines

The Word Vitrines are anonymous statements, some of which are based on found mateiral or

on real situations, some of which are invented and propositional.

The Word Vitrines’ statements generally coordinate poetic invention and banal utterance.

The format itself is a standard, preexisting one whose beauty resides in its simplicity,

flexibility and intrinsic emptiness. It, much like art, is little else than a vessel that we fill with

significance, yet even, its nondescript character (and even that of ‘art’ as an empty universal,

category), is not without significance.

By transposing this banal format from a commercial/utilitarian context into the sphere of art

the inherent formal elegance and strangeness of the format become apparent.

Readymades

True to the unprecedented category of artworks invented by Marcel Duchamp, Bethan Huws’

‘readymades’ are found utilitarian objects that unleash unforeseen (poetic) meaning through

simple recontextualisation. The punning relation of title and image, or of forms is the crux of

the ironic consistency of these ambiguously resituated objects. Often, as with Duchamp’s art,

these puns and jokes have philosophical implications.

The Chocolate Bar

The Chocolate Bar is a short film and a farcical conceit with satirical overtones. The initial

scene of the film, shot in black/white, and set in a cellar (ergo, the unconscious) represents

an irrational dream sequence. It begins with a ludicrous, nonsensical dialogue about a Mars

bar between two almost identical protagonists. Various elements drawn from the art of

Marcel Duchamp make an appearance: a Bottle Rack and an androgynous man descending

a staircase dressed in a traditional woman’s costume, that is capped by a traditional, Welsh,

male’s, large-brimmed hat. This figure is outlandish in appearance. He/She is one of three

clonal protagonists all played by the same actor. The dialogue revolves around a chocolate

bar, puns on the word ‘Mars’ and ‘bar’ and nonsensical misunderstandings between the

interlocutors. The strange object in the background, suspended in space like a UFO

(Unidentified ‘Floating’ Object), is Duchamp’s Bottle Rack. A close-up dissolving, blurred

image of this object transitions between the two parts of the film – the dream sequence in the

basement and the remainder of the film, located outdoors and filmed in colour. Another

blurred close-up detail of the Bottle Rack opens the film and is followed immediately by the

film’s title appearance on the screen. Thus the Bottle Rack occupies doubly critical places in

the film and so presents itself as its key. It imputably signals the film’s (and art’s)

propositional condition and its mediating status between thought and reality.

In the context of consumerist, capitalist driven, materialist culture, whose standard fare is

‘reality’ TV and film, the final scene from The Chocolate Bar could be taken as an anodyne

spoof of Hollywood’s spectacle fetish, which caters to ignorance, indulges anti-social

behaviour and amounts to little more than grotesquely ‘naïve’ realism devoid of any capacity

for reflexive thought. The Chocolate Bar’s multivocality and irony represent the complete

negation of that.

Bethan Huws is currently in residence at DAAD, Berlin ; she has already exhibited at the University

Gallery, University of Massachussetts, Ahmerst, the Kunstmuseum in St Gallen, K21 in Dusseldorf,

the Bonnefantenmuseum in Maastricht, the Tate Modern, the Düsseldorf Kunsthalle, the Henry Moore

Institute, Leeds, the Bern Kunsthalle et will have an exhibition next year the Museum Serralves, Porto.

This press release is an abstract of Gregory Salzman « Notes …(to be used) », A viewers’ Manuel to

the exhibition BETHAN HUWS, University Gallery, University of Massachusetts/Amherst, 2008

...................................

Pavel Braila - Want

Yvon Lambert, Paris, is pleased to announce the second exhibition of Pavel Braila, Want.

New works ranging from 2007-2008 will be presented.

WANT, red neon tube on black plastic background, 100x80cm

The word WANT, is outlined 10 times in red neon. It will light up in 10 steps from the center

to the edge, each step increasing the size of the word and the amplitude of its meaning. At

the maximal lighted step though the word becomes impossible to read.

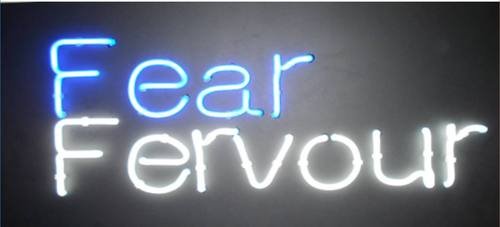

FEAR FERVOUR, white and blue neon tube, on black vinyl background 50cmx80cm

Fear is written in blue neon, Fervour in white neon. Fear, as word, is indeed longer than

fervour. But what about the feelings themselves? Does fervour last longer than fear? one

could wonder if fervour comes after fear, and think about those feelings in relationship to

reality and dreams. For Pavel Braila, born in 1971 in the USSR, this piece addresses also

soci-political issues of the past and present of two generation.

WHITE PROMENADE, video and Plunge, (dv, b/w, sound, 8min)

These two pieces are the continuation of a series of performances that Pavel Braila did

sometime ago such as ‘Pionner’, 1997, ‘Recalling events’, 2001, ‘Work, 2002. Back then, he

was dealing with basic natural materials (white paper and the landscape, blackboard and

white chalk, black soil and white paper) and involving himself in their manipulation. In each of

these works he intended to keep the neutrality and ‘naturalness’ of a material and mix it with

uncomplicated movement. In all these simplicity, the artist says he’s “trying to raise

questions and new sets of associations, which may be quite ambiguous despite the brevity

and apparent straightforwardness that is shown.”

In White promenade Pavel Braila decided to use an untouched snowed field as a screen for

a night projection. On the snowed-screen he projected the trees from around the field where

the performance took place. The projection created an open air cinema. Entering in the

shaped ‘screen’ he walked in a rectangular path from the edge to the centre, destroying the

intact surface and in the same time building a new one, such a construction through

deconstruction. Filming it from above I treated the screen as a canvas, and in this way the

video becomes a painting that is gradually completing itself by the action in it.

‘THE PLUNGE’ (dv, color, sound, 6min) shows again the process of “building by destroying”.

In this piece Pavel Braila used paper, he chose this material because it is one of the oldest

medium to spread information and because the artist likes to work with this clean, flexible

and noisy material.

The ‘Plunge’ also starts from a white ”stage” (screen/canvas) - a point zero, composed of a

pile of 105 white sheets of paper, 4x3m each. The action is filmed from above, the performer

is lying on the white surface. Action begins as an exploration of an existing surface by

ripping, squeezing, and stretching sheet after sheet. The space is being constantly distorted

and transformed, the performer never stops, longing to grab another layer, the process of

creative destruction keeps going on.

The series of paintings “My Father’s Dreams” is related to the hopes of Pavel Braila’s father

towards him when he was younger, at different stages of his childhood. “My father had many

aspirations but never thought that his son’s career would be related to art. When I became

established as an artist, my father somehow acknowledged my choice, but I could still feel

the “generation gap” and see his scepticism towards my work. “What kind of artist are you if

you cannot paint a portrait?” I decided to commission a professional painter to ‘realize’ some

of the dreams my father had for me. What were those dreams? When I was in a cradle?

Cosmonaut. When I was a bad pupil in elementary school? Refueler at a petrol station or a

watch repairer. While I was still in school, he wanted my sister to play the Violin and me to

play the accordion, as our elder cousins were doing. Before I went to university, my father

wanted me to study agronomy and to become eventually a Winemaker-Engineer etc. etc.”

COSMONAUT

“I was born in Soviet Union in 1971, ten years after Gagarin became the first human being in

space and the first to orbit the Earth, it was the beginning of a new era and being a

cosmonaut was the most desired profession. I was sleeping in a cradle, my father was a

young doctor, the radio was talking about Soviet space program, so my father was dreaming

that one day his son will become the first cosmonaut from Moldova“

REFUELLER AT A PETROL STATION / WATCH REPAIRER

“When I was about to finish elementary school, my father had to abandon his highest hopes

for me. Once, he told me that he could get me a job in a Petrol Station, “it’s a easy job and

doesn’t need specific education” he said. Another option was to become a mechanic in a

watch repair shop. At that time in the Soviet Union those jobs were better paid than a doctor.

Still after this discussion I decided to do my best and go to University.

Image: Pavel Braila

vernissage, saturday May 24

Yvon Lambert

108 rue vieille du Temple - Paris

Free admission