Gangs of the 80s

dal 24/5/2009 al 5/9/2009

Segnalato da

24/5/2009

Gangs of the 80s

Centre de Cultura Contemporania de Barcelona CCCB, Barcelona

Cinema, Press and Street. The point of departure for this exhibition is the figure of the quinqui, or low-life, coined by the phenomenon of juvenile delinquent cinema that had its moment of glory in Spain between 1978 and 1985. Curated by Amanda Cuesta and Mery Cuesta.

Curated by Amanda Cuesta and Mery Cuesta

From 25 May to 6 September 2009, the Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona presents the exhibition “Gangs of the 80s. Cinema, Press and Street”, curated by Amanda Cuesta and Mery Cuesta.

The point of departure for “Gangs of the 80s” is the figure of the quinqui, or low-life, coined by the phenomenon of juvenile delinquent cinema that had its moment of glory in Spain between 1978 and 1985.

Cinema quinqui involved a particular, involved and mutually feeding relation with the sensationalist press of the time, but it was also a faithful reflection of the urban planning, social, political and economic changes scourging the country during this period. The codes of representation of juvenile delinquency in cinema quinqui have survived until the present day, when the stereotype of the quinqui, having undergone an aesthetic makeover, is still a source of unconcealed fascination.

Most of the materials in “Gangs of the 80s” are audiovisual montages of these films accompanied by a very varied selection of exhibits providing context: period documentaries, press cuttings, photographs, comic books, records, cassettes, original objects, posters, film photos, town planning maps, etc.

Exhibition layout

1.- The cinema

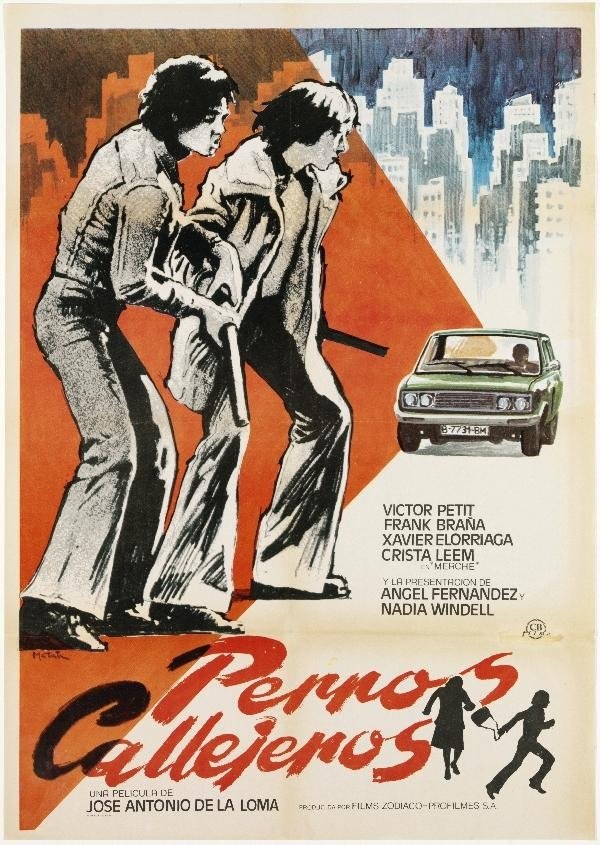

The exhibition is about what became popularly known as cinema quinqui, a genre that has yet to be given any name at all by the academic world, so it opens with the recreation of a 1980s cinema. This space will contain film photos, pressbooks and posters of the time that show how the production of films about juvenile delinquency in the Spain of the eighties was both prolific (30 films between 1978 and 1985) and enthusiastically received.

2.- The neighbourhoods of the seventies: housing estates, unemployment and depression

Behind the cinema screen lies the reality of the neighbourhoods, the germinal territory of the quinqui. A series of social emergency plans were implemented in the 1960s to deal with the enormous shortage of cheap housing. The aim was to absorb the greatest number of shanty-dwellers as quickly and as cheaply as possible. The result was dire urban planning, with poorly communicated neighbourhoods that lacked the most basic services, such as sewerage, schools and health centres. Far from addressing the social problems generated by mass immigration and uprooted citizens, these planning solutions were merely cosmetic, moving them to the city periphery. Neighbourhood movements were quickly organized to campaign for improved living conditions. The economic crisis of the seventies and high unemployment figures hit young people particularly hard.

3.- New free-time activities: the amusement arcade

At the heart of the exhibition is a reconstruction of the amusement arcade, because this lay at the heart of the world of adolescents, the central figures of “Gangs of the 80s”. These venues were omnipresent in the new film genre, representing the emergence of a new culture and new free-time activities which, for the first time in our country, put the 1970s generation of youths in touch with the youth culture industry in its international context, with its forms of capitalist consumerism. This section uses film excerpts to outline the fundamental elements of escape in the lives and feelings of adolescents: friends, sex and drugs. The amusement arcade also covers manifestations of the pop culture that were happening when cinema quinqui was at its peak, presenting similar images of rebellion, escapism and marginality in the form of comic books and music.

4.- The street: life on the edge

By 1975, all children between 6 and 13 years of age received compulsory schooling, but 25% of the over-14s were excluded from the education system. At the same time, the working age –like the age of criminal majority– was set at 16. Consequently, for many adolescents there was nothing left but the street and hustling. The police and the average citizen alike were terrorized by juvenile delinquents. They seemed to have gone wild, attacking as though driven by vengeance, and didn’t think twice about shooting, stabbing or reckless driving. Many of these delinquents were drug addicts and stole when in withdrawal to get their daily hit. Heroin became a real pandemic, as shown by the front pages of various publications in the seventies and eighties. The juvenile delinquent became public enemy number one. The image of the delinquent was fixed in the popular imagination by the arrest of El Vaquilla, shown live by TV3.

5.- Quinqui-stars

Arrest, reformatory and escape. The adventures of the juvenile delinquent were showcased on a daily basis by the sensationalist press and crime reports of the day. The limelight enjoyed by delinquents was key to their subsequent rise to icons. El Vaquilla and El Jaro (and their line) were the two brightest stars with the greatest media potential in the galaxy of names of juvenile delinquency of the eighties.

Irresistible draws for the press and heroes of life on the edge for people in the street, they remain fixed in the popular imagination thanks to film biopics recording their exploits: Navajeros, the Perros Callejeros saga and Yo, El Vaquilla form the core of cinema quinqui. Press cuttings and a variety of objects present the lives and lines of both of these delinquents. Alongside the special attention reserved for El Vaquilla and El Jaro, the newspapers were full of anonymous portraits of hundreds of juvenile delinquents dangerously at large, which take up a whole wall of the exhibition.

6.- The reformatory

The juvenile courts had three options for dealing with the problem of child delinquency. The first was to return the minors home, provided the parents agreed. The second was to send them to reformatories, known as school-homes. Many children ran away at the first opportunity, largely because ill treatment was the order of the day. The third option, reserved for the most dangerous delinquents, was prison. In 1979, there were just 14 prison places specifically for children, so many were put into prisons for adults. In the 1980s, some centres offering vocational training and rehabilitation were opened, such as the Centre for Difficult Minors in Carabanchel, Madrid, but there were still insufficient places. In 1981, 47,802 children under the age of 14 were detained in 515 prison centres due to abandonment by their families or made wards of court for criminal action or potentially criminal behaviour. This information is represented by photographs, documents and audiovisuals.

7.- From the rooftops, I can see the city

Not only were prison installations obsolete, there were also the problems of overpopulation and lack of resources. The Francoist inheritance left behind a system based on the harshest repression and punishment. Additionally, ordinary prisoners suffered as a result of the various processes of amnesty for political prisoners that began in 1975. The situation exploded in 1977, when thousands of inmates took to the roofs of prisons across Spain. This movement led to the creation of the COPEL (Coordinating committee of Spanish prisoners for reform). It called for the abolition of the repressive legislation and prison institutions of Francoism, involving reform of the penal code, the purge of “fascist” civil servants and the construction of new, more habitable prisons. Over the next few years, riots, hunger strikes, jailbreaks and self-injury became the order of the day. This space presents a photographic record of these series of riots and a sample of the publications written in prison by the inmates.

This section includes a small exhibition by Basque artist Roberto Francisco Cuesta. It comprises a hitherto unshown series of 22 photographs of the insides of cells at Carabanchel prison immediately after it was vacated in 1999.

8.- The myth lives on

This section looks at the effects produced by the quinqui phenomenon after its heyday in the street, in the press and in film. There is no avoiding the fact that most of the people involved, in both fiction and reality, came to a tragic end. In addition to this information, a display case contains biographies of ex-convicts, a literary sub-genre in its own right that offers an indelible record of life in prison.

As an icon, the quinqui of the eighties lives on in present-day representations of juvenile delinquency and low life. The forums and audiovisual work circulated on the Internet by the fans of cinema quinqui make it quite plain that the myth has gone into free flight.

9.- The exhibition’s crowning piece: the Getafe Altar

Presiding over the exit is a large-scale reproduction of the Luz y Vida (Light and life) painted by Teo Barba in the parish church of La Alhóndiga, in Getafe (Madrid). In it, Saint John, beside Christ at the Last Supper, is represented by José Luís Manzano. The lead actor of foremost films of cinema quinqui such as Navajeros and El Pico spent the last three years of his life in this part of Madrid. The Getafe mural functions as a very appropriate and distressing metaphor for the death and absolute mythification (mystification) of the figure of the quinqui as a local hero.

Catalogue

The catalogue is designed as an essay about the figure of the quinqui, seen from four viewpoints:

Amanda Cuesta (curator) explains the political and socioeconomic context that produced the juvenile delinquent of the eighties in Spain.

Mery Cuesta (curator) outlines the conceptual basis of cinema quinqui as a genre and analyses its close relation with the sensationalist press.

Eloy Fernández Porta (writer) analyses the figure of the quinqui in comic books and literature and as a genre.

Sabino Méndez (musician) provides a retrospective autobiographical account of the music trends surrounding delinquent youth in the eighties.

In addition to these four texts, the catalogue includes an anthology of comic book artists, a glossary of terms associated with delinquency and fact files for all the films of cinema quinqui.

Opening concert

Street rumba is the music associated with the phenomenon of delinquency in the eighties and its translation to the big screen. The referents of this musical genre are Los Chichos, Los Chunguitos, Bordón 4 and Las Grecas. The music is the thread leading to the present day. The musical and thematic legacy of this “other scene” of the eighties has been picked up by many young groups that both pay tribute and work with the same musical themes and atmospheres today, in their neighbourhood, in the street, in the same territories where the genre germinated over 20 years ago. The concert, headed by José El Pantanito, organizer of events of the Neocalorrismo phenomenon and director of Rumba Tunning production company, will feature various representatives of the young street rumba movement, covering classics from the quinqui repertoire such as Maldita Droga (Tony el Gitano), La cachimba (Las Grecas) and Soy un perro callejero (Los Chichos).

Press contact

Mònica Muñoz telephone: 933 064123, 933 064143, e-mail premsa@cccb.org

Press conference: 25 May, at 12 midday

Opening: 25 May, at 7 p.m.

CCCB

Calle Montalegre 5 - Barcelona

Tuesday to Sunday and public holidays: 11 a.m. to 8 p.m.

Thursdays: 11 a.m. to 10 p.m.

Closed on Mondays except public holidays

Admission

Admission fee: 4.50 €

Two-exhibition pass: 6 € / 4.50 €

Concessions: 3.40 € on Wednesdays and for senior citizens, large families, students under the age of 25 and group visits (minimum 20 persons)

Free admission for under-16s, Friends of the CCCB, senior citizens in possession of a Tarjeta Rosa card, the unwaged, on the first Wednesday of the month and Thursdays between 8 and 10 p.m.