The Jazz Century

dal 20/7/2009 al 17/10/2009

Segnalato da

Francis Picabia

Man Ray

Janco

Otto Dix

Max Beckmann

Frantisek Kupka

Aaron Douglas

Palmer Hayden

Archibald Motley

William H. Johnson

Arthur Dove

Sturat Davis

Piet Mondrian

Henry Matisse

Jackson Pollock

Jacob Lawrence

Romare Bearden

Bob Thompson

Jean-Michel Basquiat

20/7/2009

The Jazz Century

Centre de Cultura Contemporania de Barcelona CCCB, Barcelona

This exhibition offers an across-the-board reading of its complex history, based on a chronological structure providing a narrative thread that follows a timeline marking the main events in the history of jazz. The display guides visitors through examples of the rich feedback that exists between Jazz and other arts, from the first artists to notice and use this fertile relationship in the earliest days of jazz, such as Picabia, Gleizes, Man Ray and Janco, to artists like Otto Dix, Max Beckmann and Frantisek Kupka, those from the famous Harlem Renaissance, and American modernist painters like Arthur Dove and Sturat Davis. Curated by Daniel Soutif.

curated by Daniel Soutif

The Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona presents the exhibition “The Jazz Century”, curated by philosopher and art critic Daniel Soutif, which will run from 22 July to 18 October 2009.

Along with the cinema and rock, jazz is one of the most important artistic events of the 20th century. This musical hybrid that emerged in the early years of the last century has run the century through, marking every aspect of world culture with its sounds and rhythms.

“The Jazz Century” presents a chronological account of relations between jazz and the arts throughout the 20th century. It shows us how the sound of jazz has nuanced all the other arts, from painting to photography and from the cinema to literature, not forgetting graphic design and cartoons.

The exhibition is organized chronologically along a timeline off which open many smaller independent exhibitions that showcase relations between jazz and other artistic disciplines, thereby explaining the history of the century using music as a leading thread.

SECTIONS OF the exhibition

1. before 1917

It is impossible to put a date to the birth of jazz, though the year 1917 is considered crucial due to the conjunction of two decisive events. In the February, the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, an orchestra of white musicians, made the first record with the word “jazz” (or, to be precise, “jass”) on the label. In the November, the US Army closed down Storyville, the prostitution district of New Orleans, whose famous brothels had employed many musicians; the vast majority then decided to move to the north of the United States, specifically Chicago and New York. However, we must not overlook the many earlier manifestations (minstrels, gospel, coon songs, cakewalk, ragtime) that heralded the musical phenomenon that was about to transform the century and which long before had inspired many artists.

2. the jazz age in the US 1917-1930

World War I was followed in the States by the surprising fashion of jazz music, acclaimed in 1922 by Tales of the Jazz Age by Francis Scott Fitzgerald. It was such an important fashion that the expression “the jazz age” coined by the writer has been constantly used to refer not just to the music that provided the soundtrack but also to an entire age and even a “jazz generation”.

Testimonies to the jazz age included the fabulous illustrations decorating the scores of the latest hits and various photographs by Man Ray (specifically one entitled Jazz from 1919) and many other works by American artists, such as James Blanding Sloan, and others who lived in the States, such as Miguel Covarrubias and Jan Matulka.

3. Harlem Renaissance 1917-1936

While white America lived its jazz age, for the first time in history Afro-Americans experienced true cultural recognition with the movement that would come to be known as the Harlem Renaissance. While the jazz of Louis Armstrong or Duke Ellington was definitely one of the most important aspects of this creative effervescence, music was not the only field of creation. Behind foremost figures such as the writer Langston Hughes and the painter Aaron Douglas, a host of artists produced a prolific body of literary and visual masterpieces for which music was a favourite theme. Although this was an essentially black movement, white artists such as Winold Reiss and Carl van Vechten also played an important part.

4. Wild years in Europe 1917-1930

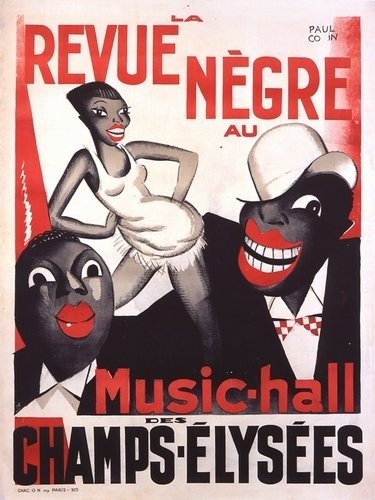

During World War I, the Harlem Hellfighters, the regimental band of James Reese Europe, had the privilege of introducing the new syncopated rhythms into Europe. When hostilities ended, every aspect of culture in the old continent was infected by the jazz virus. The arrival in Paris in 1925 of La Revue Nègre, with Josephine Baker, marked the peak of the invasion of this Tumulte noir, as it was christened by Paul Colin’s famous work. From Jean Cocteau to Paul Morand, Michel Leiris and Georges Bataille, countless writers were inspired in some way by this inexorable tide. From Kees van Dongen to Pablo Picasso and George Grosz, the phenomenon was just as keen in the field of the plastic arts.

5. the swing era 1930-1939

The jazz age was followed by the fashion of swing and big bands, whether black, in the case of Duke Ellington and Count Basie, or white like those conducted by Benny Goodman, Tommy Dorsey and Glenn Miller, who made the masses dance in the explosive thirties.

When the talkies reached the cinema, a host of musical comedies reflected this new craze and its seductive syncopated rhythm, which also inspired many artists. In the US, despite their differences, modernist Stuart Davis and regionalist Thomas Hart Benton shared an interest in the music. In Europe, František Kupka produced various paintings devoted to the jazz that specialists such as Charles Delaunay termed “hot” to differentiate it from its more staid derivatives. The close of the decade was marked by an event that was to determine the future: Alex Steinweiss, a young known graphic designer, created the first album cover for Columbia...

6. Wartime 1939-1945

World War II left a dramatic mark on Western culture. Thanks to the V-Discs produced for the US Military, music went with the soldiers into battle, and hostilities did not undermine the influence of jazz on other artistic fields. Piet Mondrian, who had just arrived in New York, discovered boogie-woogie, which was key to his latter works. In the field of dance, William H. Johnson introduced the jitterbug, the latest dance craze. At the same time, in Paris, the Zazous, probably named after a song by Cab Calloway, stood out for their eye-catching zoot suits, proof of their rather daring opposition to the invaders. Jazz became very popular in France, which explains Jean Dubuffet and Henri Matisse’s interest in it. The latter took his scissors to coloured paper to make Jazz, his famous limited-edition book.

7. Bebop 1945-1960

The advent of bebop at the end of the war led to a modernization of jazz, and in the field of painting abstract expressionism started to take off. Some of its exponents, specifically Jackson Pollock, found a direct source of inspiration in the jazz music they constantly listened to. With the microgroove came a new artistic field: album covers. David Stone and Andy Warhol, Josef Albers and Marvin Israel, Burt Goldblatt and Reid Miles were among the dozens of graphic designers, some known, some anonymous, trying to seduce music-lovers with a strict format: 30 x 30 cm. Nor was the cinema ultimately immune to the contagion of modern jazz. Just two examples of the dozens of films that used it are Ascenseur pour l’échafaud [Lift to the Scaffold] by Louis Malle and La Notte [The Night] by Michelangelo Antonioni.

Jazz-Art in Barcelona

Meanwhile, in the Barcelona of the early fifties, a revived Hot Club-Club 49 was the focus for the most active artists of the time and one of the most interesting outlets for this fusion of jazz and the arts. The “Jazz Salons” of those years included works by Tàpies, Tharrats, Ponç and Guinovart, among many others.

8. West Coast jazz 1953-1961

According to the jazz bible, bebop was New York black whereas the typical West Coast style, close by the Hollywood studios, was white, refined and so cool that many were quick to label it sugar-coated. In fact, despite a more benign meteorology and its great subtlety, West Coast jazz had a strong personality and a force of its own. Nonetheless, the typical graphic design of the record labels clearly reflected the contrast between the two coasts of America: big geometrical lettering and grainy portraits of black musicians in the east, and sunny beaches with pretty blondes frolicking beside the sea in the west... These sunny holiday images should not blind us to the fact that the California of that time was also one of the foremost venues of the union between jazz and the poetry of the Beat Generation.

9. The free revolution 1960-1980

In 1960, Ornette Coleman recorded Free Jazz. This record, with its two-fold meaning and a cover reproducing White Light by Jackson Pollock, established a new set of rules: the modern period gave way to the free avant-garde... This free revolution, contemporary with black liberation movements (Black Power, Black Muslims, Black Panthers) was reflected in the plastic arts by the works of artists both known and anonymous: Romare Bearden, in his mature period, Bob Thomson, who died before his time, and even, in Europe, Englishman Alan Davie. One of the unforgettable marks of this radical change was Appunti per un’Orestiade africana, a surprising film by Pier Paolo Pasolini in which he draws together the free improvisations of Gato Barbieri with Aeschylus and Africa.

10. Contemporaries 1980-2002

It may not always be evident, but the presence of jazz in the field of the arts, which have ceased to be modern and are now contemporary, should not be underestimated. Proof of it are the works pervaded by black music of Jean-Michel Basquiat and his predecessor, Robert Colescott. Though different in form, the video work by Christian Marclay and Lorna Simpson also confirms its presence, as does the marvellous photograph by Canadian artist Jeff Wall, inspired by the prologue of Invisible Man, the great novel by Ralph Ellison. Finally, the little blue train created by the mythic Afro-American artist David Hammons, running endlessly through a landscape of coal mountains and grand piano lids, marks the end of the exhibition: if the 20th century, the Jazz Century, has really ended, the train of the music that accompanied it continues to roll.

“The Jazz Century” is a co-production of the Museo di Arte Moderna di Trento e Rovereto (MART), the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris and the Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona (CCCB).

Image: Paul Colin, pòster per a Revue nègre, 1925

Press conference: 21 July, at 12 midday

Inauguration: 21 July, at 7 p.m.

CCCB

Calle Montalegre 5 - Barcelona

Opening times

Tuesday to Sunday and public holidays: 11 a.m. to 8 p.m. Thursdays: 11 a.m. to 10 p.m.

Closed on Mondays except public holidays

Prices

Admission fee: 4.50 €

Concessions on Wednesdays (except public holidays) and for senior citizens and students: 3.40 €

Free admission: under-16s, the unwaged, Friends of the CCCB, Thursdays from 8 to 10 p.m., and Sundays from 3 to 8 p.m.