Mixed Use, Manhattan

dal 9/6/2010 al 26/9/2010

Segnalato da

Alvin Baltrop

Bernd Becher

Hilla Becher

Dara Birnbaum

Jennifer Bolande

Stefan Brecht

Matthew Buckingham

Tom Burr

Roy Colmer

Moyra Davey

Terry Fox

William Gedney

Bernard Guillot

David Hammons

Sharon Hayes

Peter Hujar

Joan Jonas

Louise Lawler

Zoe Leonard

Sol LeWitt

Glenn Ligon

Robert Longo

Vera Lutter

Danny Lyon

Babette Mangolte

Gordon Matta-Clark

Steve McQueen

John Miller

Donald Moffett

James Nares

Max Neuhaus

Catherine Opie

Gabriel Orozco

Barbara Probst

Emily Roysdon

Cindy Sherman

Harry Shunk

Janos Kender

Charles Simonds

Thomas Struth

James Welling

David Wojnarowicz

Christopher Wool

Lynne Cooke

Douglas Crimp

9/6/2010

Mixed Use, Manhattan

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid

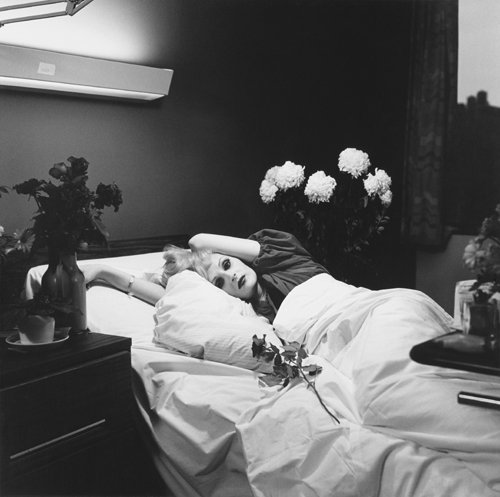

Photography and Related Practices 1970s to the present. The show includes several important photographic series: Peter Hujar's nighttime photographs taken in 1976 on the West Side of Manhattan from the Meat Packing district south to the financial district; Alvin Baltrop's Hudson River pier photographs from the decade 1975-86, David Wojnarowicz's Rimbaud in New York, 1978-1979, and, more recently, a number of Zoe Leonard's photographic projects from the late 1990s forward.

Selected Artists: Alvin Baltrop, Bernd and Hilla Becher, Dara Birnbaum, Jennifer Bolande, Stefan Brecht, Matthew Buckingham, Tom Burr, Roy Colmer, Moyra Davey, Terry Fox, William Gedney, Bernard Guillot, David Hammons, Sharon Hayes, Peter Hujar, Joan Jonas, Louise Lawler, Zoe Leonard, Sol LeWitt, Glenn Ligon, Robert Longo, Vera Lutter, Danny Lyon, Babette Mangolte, Gordon Matta-Clark, Steve McQueen, John Miller, Donald Moffett, James Nares, Max Neuhaus, Catherine Opie, Gabriel Orozco, Barbara Probst, Emily Roysdon, Cindy Sherman, Harry Shunk & Janos Kender, Charles Simonds, Thomas Struth, James Welling, David Wojnarowicz, Christopher Wool

Curator Lynne Cooke and Douglas Crimp

Mixed Use Manhattan, the title of this exhibition, refers to land-use zoning – specifically, to neighbourhoods or individual buildings in which a combination of commercial and residential functions is permitted. In the early 1970s, rezoning of parts of Lower Manhattan legalized a de facto situation in which artists had long appropriated loft spaces in partially de-industrialized areas as both studio and living quarters. This had generated a nascent art community which soon spawned facilities to meet the expanding needs of its inhabitants, from local restaurants to artist-run galleries and performance spaces. The efflorescence of the downtown art scene in the 1970s transformed Lower Manhattan from an area of abandoned and derelict buildings, razed blocks, and a wasted waterfront into an increasingly vital terrain for vanguard activity. By mid-decade, SoHo, the area’s epicentre, had become not only a mecca for artists and art galleries but a rapidly gentrifying neighbourhood.

The devastation of historic communities created by the financial downturn in the late 1960s in combination with swingeing slum clearance and real estate redevelopment programs created temporary wastelands that lent themselves to a range of activities and occupancies, some primarily aesthetic, others generated by the growing gay scene. Photographers, including Peter Hujar and David Wojnarowicz, began to shoot in streets where they lived and hung out, while artists such as Gordon Matta-Clark and Joan Jonas,and impresario/curator Willoughby Sharp,were attracted by the vast unregulated and deserted spaces that abounded in the blocks cleared for the construction of the World Trade Center and Battery Park City and the nearby piers on the Hudson River. Bernard Guillot, like many foreigners who visited the city at this time, was fascinated by the solitariness and the clandestine activities secreted in these local wildernesses. Whereas Guillot concentrated on the West Side, and 12th Avenue in particular, Thomas Struth, newly arrived from Germany on a residency fellowship, gravitated to deserted streetscapes across Manhattan and its boroughs. Unlike Guillot, Struth viewed his subjects through the filter of a European tradition of architectural photography, a historical genre that originated in the late nineteenth century and was carried forward in the work of Bernd and Hilla Becher, his teachers at the Düsseldorf Art Academy in the mid-1970s. At the turn of the twenty-first century, the California-based photographer Catherine Opie explicitly referenced this genre when she began a series, related to her own earlier photographs of Los Angeles strip malls, of large-format black and white photographs of the narrow lanes and winding streets of the Financial District. Devoid of people, Opie’s images take on a melancholy tone that verges on the eerie, given how populous the thriving Wall Street milieu had become in the boom years of the 1990s. Opie’s empty vistas were captured in the wee dawn hours, in contrast to the legendary images that Danny Lyon shot in 1967-8, as he lived and worked daily in the downtown area that was literally being torn apart. A group of Lyon’s pictures from his ground-breaking book The Destruction of Lower Manhattan provides the prologue to this exhibition. In conjunction with works by Struth, Guillot, Opie, and several others, including the little known William Gedney, they create a play back and forth, across generations as well as sites, that becomes one of the exhibition’s central axes.

Among the most recent works included here is Static, 2009, a digital projection by British artist Steve McQueen. The seven-minute loop combines a spiralling camera movement with a fluctuating soundtrack, filled intermittently with the relentless whirr of the helicopter in which the artist was perched. The destabilizing effect this produces is reinforced by the contrasting speeds at which foreground and background move before our eyes. As the helicopter circles the statue, the congested urban shoreline appears intermittently behind lyrical, close-ups – barely perceptibly moving – of the work’s iconic subject: memorable details include the torch held aloft, an arm clutching a book, and a serene unfocussed glance. As the probing camera circles in on what has become the world’s most famous monument - whose full title reads “The Statue of Liberty: Liberty Enlightening the World” - this proximity becomes almost threatening: challenging the integrity of the figure, putting into question its ability to maintain its values unscathed under intense appraisal. Ruminating on the legacy of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, McQueen intimates that city, nation, and the world beyond are all intimately affected by any undermining of their shared beliefs. Very different in spirit and tone is the video shot by Dara Birnbaum in 1976 titled Liberty: A Dozen or So Views, in which the artist engages a random sampling of tourists on a ferry cruising the waters watched over by Bartholdi’s grand figure. Readily participating in a survey that solicits basic information regarding their (physical) identities, her respondents appear with hindsight unexpectedly vulnerable - even poignant – so at ease, confident and forthcoming do they seem when viewed through the lens of more recent events.

Another thread – in the guise of flânerie, unstructured meandering walks, cruising – generated a number of works exhibited here, most obviously, Peter Hujar’s photographs taken in 1976 of his route through the far West Side to a deserted night-time Financial District; and more defiantly, David Hammons’ Phat Free, 1995, in whose video of a game of urban kick-the-can, we hear the rattling percussive street music before we see the image of the solitary player: tellingly, Hammons’ camera follows his subject with much the same bumpy motion as that of the can he’s kicking along in front of him. Other contributions similarly based on commonplace everyday routines take on a more structured form. Stefan Brecht, for example, turned to the camera to photograph the sidewalks he traversed daily on his walks between his apartment in the West Village and the room in the Chelsea Hotel in which he wrote. Visual counterparts to the suite of poems he was working on at the time, these images were to be the background on which the texts would be printed in a forthcoming book. Though that publication never materialized except in a handmade version, photographs and text each became the separate subject of a publication in due course. Christopher Wool’s grainy, sombre photographs also grew out of a journey between his apartment and studio, though Wool, in contrast to Brecht, usually went back and forth late at night, and his casual shooting of whatever caught his eye initially had no larger goal. An appreciation for the poetics of the serendipitous and the ephemeral, whether the mundane incident or the otherwise overlooked detail, fuels his activity in a variety media, and painting in particular. He thus shares with Zoe Leonard an interest in the minutiae of place, in the often derided and neglected marginalia that give texture and identity to a location. In recent years this acuity to particular aspects of her immediate world has propelled Leonard into a highly ambitious project that tracks the make-over of her Lower East Side community. A place once home to waves of immigrants when they first landed on American shores, this neighbourhood, too, was decimated in the 1990s by the encroachments of megastores, sky-rocketing rents, and upscale marketing.

Together with Leonard one of the few artists in this exhibition to have been born and raised in the city, Glenn Ligon brings a highly personal address to his contribution to Mixed Use, Manhattan. His laconic review of the range of apartments and locations he has lived in during four decades is conveyed in short texts whose affectionate wryness sparks images in the reader’s mind. That this works even for those not actually familiar with the particular streets or neighbourhoods he characterizes attests to the ubiquity of images of Manhattan and the city’s other boroughs in our collective memories. Based on a broad amalgam of information garnered through literature (high and low), films, television series, lifestyle magazines, and photography of all kinds, our ready responses to Ligon’s project confirm the pervasiveness of a mediated vision of Manhattan in contemporary consciousness. That ubiquity is a prerequisite for the work that the young German photographer Barbara Probst has made on her frequent sojourns to New York. Recalling a location shoot for a film or for an advertising campaign, her multi-partite works conjure a scene from various viewpoints, often capturing in the process some or all of the camerapersons at work in this set up. Seeing and being seen are inextricably linked in these ricocheting scenarios, isomorphic to the live-action film in real time that daily life in Manhattan has become. Self-consciousness, verging on occasion on self-reflexivity, informs many of the more recent works on view in this exhibition. In consequence, they are sometimes laden with a historical valence, as is the case with Matthew Buckingham’s One Side of Broadway, freighting old contestations of public space with a renewed currency; elsewhere, as seen in Emily Roysdon’s untitled work of 2001-2007, which returns to David Wojnarowicz’s Rimbaud in New York, and her more recent photographs of the piers, retrospection proves uncannily timely; while fuelling Sharon Hayes’s project In the New Future, 2005, is the recognition that public space must be contested in the face of its instrumentalization by cultural institutions and the corporate sector alike. For the generation of artists whose work matured downtown in the 1970s, public space was, for a time, there for the taking - so much so that guerrilla activities prevailed over sanctioned programs. Today, by contrast, this appropriated and sequestered terrain is once again the focus of artists, activists and others who seek to reclaim what - at least briefly - proved for their predecessors protean ground to be shaped in their own, often defiantly marginal likenesses.

Exhibition organized by Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia during PHotoEspaña 2010

Image: Peter Hujar

Opening 10 June 2010

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia

Sabatini Building, Floor 4

Santa Isabel, 52, Madrid

Hours Monday to Sat.10-21, Sunday: 10-14:30

Tuesday Closed