Ike Ude

dal 11/9/2002 al 8/11/2002

Segnalato da

Fifty one Fine Art Photography

11/9/2002

Ike Ude

Fifty One Fine Art Photography, Antwerp

His photography is infused with critical references to fashion and the media, and he investigates fashion photography as a distinct type of performance documentation. His send-ups of stock fashion poses and sexual stereotypes undermine the tenuous balance between perception and reality that fashion features and ads work so hard to achieve.

Nigerian-born Iké Udé has been living in New York City since 1982, but

first received critical attention in the mid-1990s as a result of

participation in a number of highly acclaimed international exhibitions.

This attention was also an acknowledgment of Udés impact on an active

circle of New York artists during the 1980s, when his interest in

style, fashion, and media led to his founding of the magazine aRude.

Treating the magazine as a medium in its own right, Udé played multiple

roles in its production.

Udés art insists that, while the arts have played a key role in the

politics of visual culture and representation, media and fashion are

increasingly defining visual culture. His photography is infused with

critical references to fashion and the media, and he investigates

fashion photography as a distinct type of performance documentation. His

send-ups of stock fashion poses and sexual stereotypes undermine the

tenuous balance between perception and reality that fashion features and

ads work so hard to achieve.

Beyond Decorum: In the title series "Beyond Decorum" Udé gathers

well-worn high heel pumps and men's business shirts with ties and

replaces the labels with sexually explicit personal ads. Clothes become

both a cultural uniform and a costume. A traditional shirt and tie take

on alternative sexual meanings: appearances can be deceiving when

conservative dress pumps have a transgendered owner. By combining sexual

identities assumed to be on the fringe of society with mainstream

clothes Udé questions whether appearance determines thought or behavior.

In "Beyond Decorum" Udé makes sexual desires visible and in the process

points to the cultural taboos dividing public and private propriety. He

simultaneously normalizes that which is thought to be deviant and

uncovers the diversity behind a uniform appearance. Udé is fundamentally

interested in presenting complex identities that cannot be easily

reconciled with preconceived categories.

"Covergirls" is a series of enlarged color photographs of fabricated

magazine covers. At first glance Udé appears to be spoofing Vogue, Cigar

Afficionado, and Parenting but the critique is deeper than humor alone.

As in the series "Beyond Decorum" Udé creates a visual document for a

cultural absence. Here Udé becomes the 'covergirl' gracing the cover of

Cigar Afficionado as a black man in dramatic drag make up and on

Parenting as a black baby on a walk with his white nanny. While Udés

identity changes from cover to cover the monotony of the traditional

upper-class white cover model becomes apparent.

The "Covergirl" series recalls many historical influences from Andy

Warhol's multi-media, pop art fascination with the creation of celebrity

and more recently Cindy Sherman's use of costuming to explore the

cultural icons and stereotypes of women. Warhol used repetition and

methods of mass-production in his portraits of well-known faces to

suggest that public identities were produced rather than natural. And to

a similar end Sherman makes her portraits of well-known cultural roles

overtly theatrical to unveil the superficiality of these stereotyped

personalities.

Udé, however, not only points out the construction of stereotyped

cultural identities but also sets out to present the complexity and

diversity within and among these culturally defined identities. He does

this by presenting identities that straddle several characteristics at

once: the confident black man, the privileged upper-class

connoisseur, the effeminate transsexual, and the international man with

an African family history.

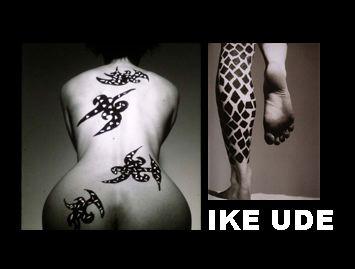

ULI Serie : Even in his most formal and politically subtle series of

untitled black and white nudes, the issues of identity are brought to

the forefront. Udé uses the conventions of the tradition of nudes in

photography and the seduction of a broad tonal range black and white

print to highlight skin as the ultimate cultural costume. In Udé's

versions of the nude he takes partial body shots and never includes the

figure's face to eliminate the possibility that these are portraits of

individuals. He draws attention to the color, texture, surface of the

skin by painting decorative patterns across the bodies of the figures in

a contrasting color. To exaggerate his emphasis on the surface and

appearance of the figures' skin some photographs include a light skinned

body juxtaposed with a dark skinned one. Nevertheless, the identity,

race, culture, and often the gender of the figure is completely

ambiguous. Skin, that costume that is considered the most immutable

determinant of identity, is rendered as a decorative covering.

by Mitra Abbaspour

FIFTY ONE FINE ART PHOTOGRAPHY

ZIRKSTRAAT 20

2000 ANTWERPEN

BELGIUM

T:32-3-2898458

F:32-3-2898459