Body and Soul

dal 20/3/2010 al 29/12/2011

Segnalato da

20/3/2010

Body and Soul

Museum fur Kunst und Gewerbe, Hamburg

Images of Human Beings from Four Millennia. A thematic exploration of the conditions of human existence with more than 100 artworks from the departments of Antiquity, China, Japan, Islam, European arts and crafts, graphic art, photography, fashion and furniture design. To celebrate the reconstruction of the main entrance hall and the new special exhibition space in the east wing, the show assembles selected masterpieces from the collection and directs the visitor's attention to the exceptional wealth, diversity and quality of the museum's holdings which comprising over 500,000 objects.

What is man? What distinguishes him? Questions which have moved human beings for millennia, constantly compelling them – us – to set out in search of new answers. To this day, the human body – the smallest social unit and a representative of ideas, desires, longings, individuals and cultures – is a favourite motif with which artists throughout the ages have inquired into the essence of man and the conditions of human existence. To celebrate the reconstruction of the main entrance hall and the new special exhibition space in the east wing, the show assembles selected masterpieces from the collection of the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe and directs the visitor’s attention to the exceptional wealth, diversity and quality of the museum’s holdings which – comprising over 500,000 objects – offer an incomparable reservoir for stories about humanity. For the duration of the show, more than 100 exhibits from the departments of Antiquity, China, Japan, Islam, European arts and crafts, graphic art, photography, fashion and furniture design will be leaving their places in the art-historical chronology of the permanent collection and uniting to create a thematic exploration of the human being – the creator and epicentre of “Kunst und Gewerbe” (“arts and crafts”) – in imagery. The objects mirror how mankind deals with such themes as birth, passion, beauty, play, conflict, individuality, veneration and death, and pave the way for the discovery of similarities and differences in various cultures’ conceptions of the body and the soul to the very present. “Body and Soul” offers an unusual perspective on the collection – playful, associative, an appeal to the beholder’s imagination.

The exhibition begins with the question as to the origins and birth of man. The motif of the nurturing mother figure holding a child is found in nearly every culture and every age. Christian depictions of the Madonna dating from many different centuries stand for the veneration of the Virgin Mary and maternal care in general. In ancient Egypt, the image of the goddess Isis nursing the boy Horus symbolized the protection offered by the family. This iconography already anticipates depictions of Mary with the Christ Child. With his red armchair Donna UP 5 (1960) – inspired by the bodily forms of a woman giving birth and chained to the child Bambino UP 6 – the Italian designer Gaetano Pesce placed the female principle of fertility into the context of the role of modern-day woman, for whom the fact of being a mother can also represent a limitation to her newly gained independence. These objects are further accompanied by a delicately worked Italian eighteenth-century christening robe, a Christ Child carved around 1500 for a Cistercian convent in Upper Swabia – where it was dressed up in costly garb and laid in a cradle on the altar for the annual nativity play – as well as a mould of 1780 for baking the figure of an infant in swaddling clothes representing a German popular custom of the time, according to which such cakes were consumed in the hope of being blessed with an abundance of children.

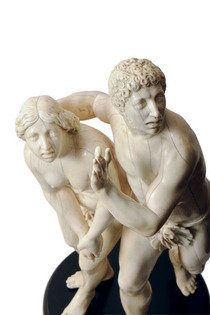

The second section of the show sheds light on the various facets of human passion. The ivory sculpture Adam and Eve after Their Expulsion from Paradise of 1645/50 by Leonard Kern shows the first human couple fleeing from the Garden of Eden. This work of ivory carving addresses the themes of fear, guilt and atonement, while also illustrating the Baroque’s emerging interest in human emotions and their dramatic depiction in art. Passion also finds expression here in a fan (1913) by Oskar Kokoschka symbolizing his obsession with Alma Mahler, erotic Japanese woodcuts (18th century) from the famous manuals for lovemaking practices, and photographs by contemporary photo-artist Nobuyoshi Araki showing young Japanese women in bondage.

Man has always been preoccupied with his own appearance and sought to influence it by changing the body itself, or with the aid of clothing and jewellery. Whereas in many cultures beauty was and is associated primarily with bodily characteristics and proportions, the modern age discovered the beauty of the mind and the soul. The neo-Classicist biscuit porcelain figural group of the Three Graces by Christoph Gottfried Jüchtzer adheres to Antique conventions for depicting female beauty. This classical motif was one which offered artists an opportunity to stage the female nude from several angles at the same time. It has lost nothing of its relevance, however, as is seen in a photograph of three African women as the Graces in Three Girls, Dahomey (1967) by Irvin Penn. Erich Heckel’s Expressionist Standing Female Figure (1912) coarsely carved in wood, on the other hand, picks up the tradition of the Venus pudica or “modest Venus”.

Play is a topic which appeals to children and adults alike. This chapter of the exhibition assembles objects having to do with play in all its myriad contexts, for example the Noh masks used in traditional Japanese Noh theatre to intensify the “mysterious charm” (yugen). Play as an element of festivities allows the participants to break social rules for a little while and recall the basic constants of human existence in a cheerful setting. A small silver skull – measuring less than two centimetres in length – was intended to remind the guests at Late Hellenistic drinking orgies of the transitory nature of opulence and life. And many artists themselves have a strong affinity to play, for instance Lyonel Feininger who, creating a toy town which he carved and painted for his children, entered the world of the child’s game while at the same time caricaturing the confinements of life in the small towns of Germany.

Physical conflict is a phenomenon shared by all of the world’s peoples. Antique mythology is full of historical and mythical accounts of fights which were taken up again in the Renaissance. A marble sculpture of 1516/17 by Christoforo Solari of Milan shows Hercules, one of the most popular Antique symbols of the triumphant struggle, overcoming the giant Cacus and stylizing victory in a heroic pose. In the world’s religions, good must triumph over evil, and protective deities and saints are placed at man’s side to aid him to this end. The depiction of the Archangel Michael victorious over the prostrate Satan is an example of how the eternal struggle between God and the devil is expressed in art. Unlike Hercules, however, the archangel does not conquer his adversary by way of physical superiority, but with the power of God, represented in the attributes of the divine messenger: The flaming sword and the shield with the sign of the Christian cross identify the angel as a representative of supernatural divine strength.

It is a long road which leads through art history from the idealistic depiction of the ruler and conqueror to the democratic and ultimately hackneyed photographic likeness for all and sundry. The image of the self represented in art history by the portrait shows the subject’s physical features and is capable of revealing the status, character, personality, even the very essence of the person portrayed. In the course of the Enlightenment, the physical appearance of the human being inspired Johann Caspar Lavater to carry out comparative studies of physiognomy in which he constructed a connection between the form of the skull and brain, the character and intellectual gifts. A portrait study by Daniel Chodowiecki, one of the most well-known German illustrators of the eighteenth century, thus served as an object of study for the “physiognomist”. The section concerned with individuality also shows such pieces as the female figure (ca. 1904) by Richard Lucksch measuring two metres in height and striking a nervously twisted pose, used to decorate the façade of a sanatorium for nervous disorders, where she represented the modern vision of woman.

The phenomenon of veneration is inherent to all cultures, and the part of the exhibition devoted to this theme brings together objects with cult status serving to represent persons and ideas. The spectrum ranges from folk art and Antiquity to the political cult and the worship of Mary and Jesus. Yet pure, unfading beauty was – and is – likewise worthy of adoration, as is expressed by the head of a boy angel whose androgynous facial features reveal the nature of his celestial being. The famous poster Viva Ché staging the likeness of revolutionary Ernesto “Che” Guevara in black against a red background stands for the present-day personality cult. This figure suffered for his ideals and was murdered by his adversaries, and is worshipped all over the world as a modern Man of Sorrows. “Che” died at approximately the same age as Jesus of Nazareth.

Death and dying constitute a central theme in all cultures and ages. Funerary objects and the decoration of the dead with jewellery are indicative of the fact that death is not conceived of as a termination, but as a connecting link to a new individual life, or a transition to a different form of existence. The skull has long played a role as an immediate expression of death: skull cults are known to have been practiced in the Middle East as early as the ninth millennium BC. Skulls are also found as relics in elaborately ornamental reliquaries of the Mediaeval Christian church and have served since the Renaissance as a vanitas motif symbolizing the transitory character of human life in comparison to the immortality of the soul. The late Alexander McQueen, a fashion designer, used the traditional symbol of the pirate as his distinctive mark, having it printed, for example, on silk scarves.

Image: Fig.: Leonhard Kern, Adam and Eva after their Expulsion from Paradise, ca. 1645/50, MKG, photo: Hiltmann/Rowinski/Torneberg

Press contact:

Michaela Hille, Phone: +49/40/428 134 – 800, Fax: 040/428 134 – 999 E-Mail: michaela.hille@mkg-hamburg.de or presse@mkg-hamburg.de

Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe

Steintorplatz D 20099 Hamburg

Opening times: Tuesdays to Sundays 11 a.m. – 6 p.m., Thursdays 11 a.m. – 9 p.m.

Entrance fees: 8 € / 5 €, Thursdays from 5 p.m., children and youths under 18 years old: free