Locus Solus

dal 24/10/2011 al 26/2/2012

Segnalato da

Raymond Roussel

Manuel Borja-Villel

Joao Fernandes

Francois Piron

Antonia Fernandez Casla

24/10/2011

Locus Solus

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid

Impressions on Raymond Roussel. the exhibition aims primarily at relocating Roussel's oeuvre in its social and cultural context, at the end of the 19th century, because otherwise it is incomprehensible. Roussel's procedure was above all a pretext for a closely referenced game with the culture of his time: the author delighted in bringing to life a veritable personal museum, in which each book, each object and each image opens out into a profusion of anecdotes, and in which the true and the false, quotation and invention, are closely interwoven.

Curated by Manuel Borja-Villel, João Fernandes and François Piron

Coordinated by Antonia Fernández Casla

Locus Solus. Impressions de Raymond Roussel is the first major exhibition devoted to this

French writer and to his profound, often underground influence on 20th century art and

literature. Raymond Roussel (1877-1933), the author of The View (1904) and Locus Solus

(1913) occupies a unique place in literature, to which he dedicated his entire life and

consecrated a large part of his fortune. In the ten works he brought out during his lifetime -

poems or verse novels, tales or plays - he aimed at creating a world from scratch in which

“imagination is everything”, and in which nothing real should impinge on the writing.

Absorbed in this enterprise and convinced of his genius, he lived through the first third of

the 20th century without paying any attention to its political upheavals or their aesthetic

consequences among the various avant-garde movements, while failing to understand

why the more conventional audience he thought he was addressing remained indifferent to

his work, and found its stage adaptations scandalous.

Often described by his contemporaries as a haughty dandy, he did indeed spend most of

his life retired from society, and though his “life was constructed like his books”, in the

words of the psychiatrist Pierre Janet, he was in reality an enthusiastic character, whose

worship of genius came firstly from his loyal attachment to his childhood memories and

reading, and subsequently from his devotion to those whom he considered to be great

minds: Jules Verne and Pierre Loti with their real or imaginary travels, the astronomer

Camille Flammarion or the poet Victor Hugo. However, he remained distinct from the last

two on this list because of his refusal of anything supernatural, which he replaced by the

absolute value of invention, set in a theatrical universe constructed by a chain of enigmas,

the solutions of which were always impeccably logical. It was above to channel his

overpowering imagination that Roussel conceived some of his works using a “highly

special procedure”, which he was to reveal only in his literary testament published after his

death: How I Wrote Certain of My Books. This procedure, “related to rhyme”, is based on

combinations of homophones and the association of words with double meanings. It is the

distance between these terms, placed invariably at the beginning and end of each story,

that would later provide Roussel with a framework for his writing as well as an

inexhaustible store of unexpected images and stories, such as the “statue of whalebones”

or the “worm playing a cithara”, in his Impressions of Africa.

The posthumous revelation of Roussel’s writing procedure has lastingly influenced his

reception, and as a result many critics have often considered him, wrongly, to be a mere

manipulator of words, thus confirming the thesis that his was a modern form of writing,

based only on self-referentiality and arbitrary constraint. Thus, the exhibition Locus Solus

aims primarily at relocating Roussel’s oeuvre in its social and cultural context, at the end of

the 19th century, because otherwise it is incomprehensible. Roussel’s procedure was

above all a pretext for a closely referenced game with the culture of his time: the author

delighted in bringing to life a veritable personal museum, in which each book, each object

and each image opens out into a profusion of anecdotes, and in which the true and the

false, quotation and invention, are closely interwoven.

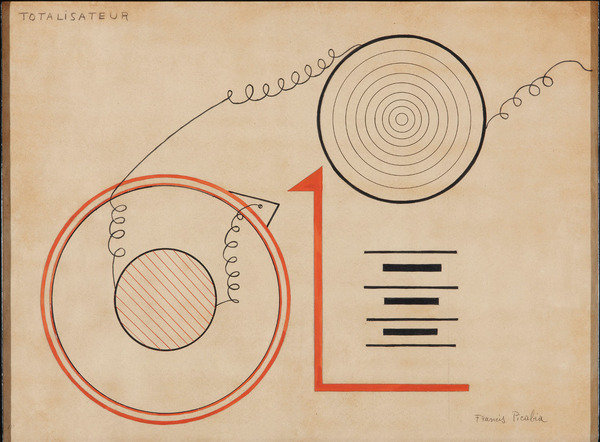

Even if he was only to become aware of the fact late in his life, during his lifetime Roussel

attracted a great deal of enthusiasm among a generation of artists and poets. It was one of

the performances of Impressions of Africa in 1912 that Marcel Duchamp, who was there

with Guillaume Apollinaire Francis Picabia, was to recall and mention as a primary

influence on his Large Glass. The photographic precision and laconicism of Roussel’s

writing, his taste for technical and scientific innovations, as well as the absence of any

psychological depth in his characters, who come over as simple puppets lacking in depth,

come together to make Roussel one of the sources of the “bachelor machines”, as the

writer Michel Carrouges pointed out in 1954.

Marcel Duchamp seems to have made Roussel’s name known to the Parisian Dadaists,

who were to discover him during performances of Locus Solus in 1922. Philippe Soupault,

Paul Eluard and Roger Vitrac then took up his defence in Dada and then Surrealist

reviews, seeing him as an equivalent of Douanier Rousseau, or comparing the park in

Locus Solus to the deserted esplanades of Giorgio de Chirico. A “Rousselian” cult then

progressively took form: ‘the President of the Republic of Dreams”, (Louis Aragon), “the

greatest mesmerist of modern times”, (André Breton), “his eye glued to his microscope”

(Robert Desnos), Roussel was, for the Surrealists, the person who engineered “the

escape from the world of reality into that of conception” (Michel Leiris). Leiris was linked to

Roussel though his father, who was the Roussel family’s business manager, and he

closely associated his passion for the author with his own work as an ethnologist, placing

under the auspices of Impressions of Africa his first ethnographical expedition to Dakar-

Djibouti in 1931-1932, which was partly financed by Roussel, and which was directed by

Marcel Griaule. In the pages of Georges Bataille’s review, Documents, Leiris hailed the

depiction in Impressions of an Africa that was so marvellous that its exoticism owed

nothing to the colonial stereotypes of the time.

Reading Roussel was also fundamental to the creation of Salvador Dali’s paranoiac-critical

theory during the 1930s. To Roussel’s doubling of words, Dali answered with a doubling of

images; and it was the crystal transparency of Roussel’s texts, in particular his poem The

View, that provided Dali with a model for his “rigurosa lógica de la Fantasía”, confirming

the necessary exactitude of the imagination, thus giving rise to visions that materialise

subconscious desires as closely as possible.

In an article published in the review Le Surréalisme au service de la Révolution, in 1933, a

few months before Roussel’s death, Dali paid homage to the “ungraspable” character of

New Impressions of Africa, his last published poem, which he had worked on for ten years.

In this text, Roussel sacrificed the transparency of his writing for a principle of permanent

digression. Practically every word of the poem is a pretext for an analogy or comparison,

while opening a breach in the text from which then surges a series of commentaries,

judged to be “impenetrable” by Dalì. Roussel’s insistence on concision forced him to

increase the number of ellipses as his text swelled with digressions. Probably with a view

to finding a system that would simplify reading it, and point to an order in the intertwining

of narrative threads, Roussel opted for a typographical device, cutting up his text with

brackets nestled in layers. Along with the mysterious illustrations, which Roussel ordered

from the conventional painter Henri Zo, New Impressions stands as a complex book-object

which was to inspire several “reading machines”.

The reception of Roussel after the Second World War was essentially the work of the

Collège de ‘Pataphysique, founded in Paris in 1948 to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of

the publication of Alfred Jarry’s Docteur Faustroll. Thanks to the publications of the

Transcendant Satrape Jean Ferry, who set about an erudite, literal deciphering of

Roussel, without attempting to interpret him, and the “Machine for reading Roussel” (1954)

by the Argentinian artist Juan Esteban Fassio, the trend was now to adhere literally to

Roussel’s texts and provide them with illustrations. It was for the Collège that Jacques

Carelman produced, on the invitation of Harald Szeemann, two sculptures based on

descriptions in Locus Solus for the Bachelor Machines exhibition (1976), while Jean-

Christophe Averty was to conceive a televised version of Impressions of Africa (1977).

Since the 1960s, Roussel’s oeuvre has been widely translated, especially in the USA

thanks to the poet John Ashbery who, after carrying research in Paris during the 1950s

into the author of Locus Solus, founded a review of the same name with, among others,

Harry Mathews, who wrote a brilliant Rousselian pastiche with Georges Perec in 1977.

The influence of the review Locus Solus, which was little noticed at the time, nevertheless

brought Raymond Roussel’s name to the poets of the New York School. Meanwhile, the

writings of Michel Foucault, Michel Butor and Alain Robbe-Grillet were the source of

interest in Roussel among numerous artists, including Vito Acconci, and in the 1980s in

Los Angeles, Allen Ruppersberg, Morgan Fischer and Mike Kelley, centred around the

recently rediscovered work of the French artist Guy de Cointet.

Readings and interpretations of Roussel have changed enormously over the past century,

and the figure of this writer, who throughout his life guarded against revealing the slightest

information about himself and kept an air of mystery around the genesis of his works, has

become an essential model of the artist, standing as the Minotaur at the centre of the

labyrinth of his work. At the end of the 1980s, the discovery of a considerable stock of

archives and manuscripts, many of them unpublished, now conserved at the Bibliothèque

Nationale de France, has shed new light on his oeuvre, confirming Michel Leiris’s view that

“no one has ever touched so closely the mysterious influences that govern the lives of

men.

On occasion of the exhibition, a catalogue will be published, comprised by texts by authors such as

Patrick Besnier, Annie Le Brun, Astrid Ruffa and Linda Henderson, that put the inspiration and

writings by Raymond Roussel in the context of the cultural environment he lived in. The volume will

also include texts by the curators of the show, Manuel Borja-Villel, João Fernandes and François

Piron, as well as an interview that Piron did to John Ashbery regarding Roussel’s reception in

France and the United Stated, and his influence on a whole generation of artists and writers during

the seventies.

The book also takes into account Roussel’s presence in the works by Salvador Dalí and Marcel

Duchamp through several essays. It is completed with an anthology of texts written by artists such

as André Breton, Robert Desnos, Jean Cocteau, Paul Éluard or Salvador Dalí about Roussel’s

influence on their work.

Related activity:

Conference Locus Solus. Impressions on Raymond Roussel.

With João Fernandes and François Piron (26 October 2011, 19.30h, Sabatini Auditorium)

Concert Pierre Bastien. Une danse de sons

Thursday 27 October 2011. Protocol Room, Sabatini (1st floor).

Showings at 19.00h and 20.00h

Organized by:

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía

Museu de Arte Contemporãnea de Serralves (Oporto)

Image: Francis Picabia, Totalizator, 1922, acuarela, tinta y carton 55x73cm

Gabinete de Prensa tel 91 7741005 / 1006 Milena Ruiz Magaldi prensa1@museoreinasofia.es - prensa2@museoreinasofia.es

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía

Sabatini Building, 1st floor

Santa Isabel, 52- Madrid

Hours: Mon-sat 10-21, sun 10.14.30

Admission: 6 euro, 3 concessions