Painting Is History

dal 10/7/2012 al 9/8/2012

Segnalato da

Charles Browning

The Chadwicks

David Fertig

Joe Fig

Valerie Hegarty

Steve Mumford

Jay Grimm

Edward Winkleman

10/7/2012

Painting Is History

Winkleman Gallery, New York

A group exhibition featuring work by Charles Browning, The Chadwicks, David Fertig, Joe Fig, Valerie Hegarty and Steve Mumford. While the practices of these artists vary greatly, they are united by their interest in the traditional use of painting to record history. For much of art history, painting occupied a central role in the formation of shared memory.

curated by Jay Grimm and Edward Winkleman

Featuring work by Charles Browning, The Chadwicks, David Fertig, Joe Fig, Valerie Hegarty, and Steve Mumford

Winkleman Gallery is pleased to present “Painting is History,” a group exhibition featuring work by Charles Browning, The Chadwicks, David Fertig, Joe Fig, Valerie Hegarty and Steve Mumford. The show was co-curated by Jay Grimm and Edward Winkleman. While the practices of these artists vary greatly, they are united by their interest in the traditional use of painting to record history. For much of art history, pain ting occupied a central role in the formation of shared memory. The pictures of historical events became the way in which they were remembered and commemorated. During the 18th and 19th Centuries, the academies of Europe placed history painting at the pinnacle of artistic achievement privileging the mode above all others.

Of course, this idea no longer holds. Film and digital media are the primary means of recording history, and painting is considered suspect by many observers for the very reason of its former function in this regard. Indeed, to be a contemporary painter is to often reject the past or to forget it altogether—to paint without memory. And yet, there are contemporary artists who are intrigued by possibilities within painting for recording and imagining human affairs. This show presents a small group of artists who explore this possibility.

Charles Browning’s work often riffs on the overblown allegories and idealizations common to 18th and 19th Century painting, suggesting that beauty is but a commodity and that the painter is simply producing items that are consumed in much the same way as any other luxury goods. Despite this critical take on the act of painting, it is obvious from the quality of his work that he takes the craft seriously. The tension between the overt beauty of his paintings and their underlying critique of inflated notions of decoration drives his art. In Necessary Arrangement (It’s Only Torture If They Are Human), Browning depicts an artist at work, painting from life a scene of brutal torture. A man is pinned to the ground, arms apart, posed as if being crucified while dogs tear at his flesh. Despite this violence, other figures, Native and African Americans, stand around, seemingly unaware of the horrible scene before then, and the painter hims elf is smiling. These figures reference the American colonial painters penchant for inserting native and enslaved peoples into their works to signal that the scene is in the new world, but the focus remains on the affairs of the Europeans, and these figures are marginalized and passive. However, the twist here is that the man on the ground appears to be white. The painter is seemingly at work on a crucifixion; the ‘necessary arrangement’ is that he needs a model to accurately depict Christ’s suffering. Thus, the tableau mocks the grandiosity of much religious painting and at the same time, turns the tables, allowing the powerless natives to witness, but not be subjected to, humiliation.

The Chadwicks are a fictitious family, once prominent in colonial America and in England, whose tremendous wealth and influence is dissipated, but who live as recluses in the shells of their former grandeur. The Chadwicks were voracious art collectors and thought deeply about the manner in which paintings create a fictive space. The editors of the Chadwick Family Papers, Jimbo Blachly and Lytle Shaw, have on many occasions presented different aspects of the family's collection to the public. In so doing, they have often explored the 17th Century Dutch genre painting tradition and argue that this movement undermined the Grand Manner and punctured the pretentions of history painters. Their inclusion in this show serves as a reminder that even at the time of their production, many intelligent viewers were questioning the assumptions that painted pictures could really manage the heavy expectations placed on them.

The paintings of David Fertig, by contrast, seem to embrace the idea that paintings of historical events can resonate. He takes as his subjects the military activities of the Napoleanic era, referring to original source material to get a sense of the uniforms and equipment of the day. Despite this attention to detail, his works are not meticulous renderings, but rather his paint handling is informed by the New York School, with a slashing approach to paint application and surface. Beneath it all lies a pulsing enthusiasm for the ability of paintings to convey an appreciation of the weight of history.

Joe Fig’s work has always focused on the actual creation of art. His earlier work consisted of detailed sculptures that meticulously recreated, in miniature, the studios of well-known artists. More recently, he has returned to canvas painting, keeping his attention on artist’s activities. In a manner that is at once slightly ironic and deeply touching, Fig depicts painters at work in a way that calls attention to the fictions they create, and also to the waning influence that figurative art experienced in the late 19th Century. In Study for Napolean 1814, Fig depicts the painter Messonier at work en plein air next to an image of the famous general astride a horse. Messonier was acclaimed for his images of Napolean and he was probably one of the last figurative history painters to enjoy such prestige. However, Napolean died when the artist was only 6 years old. Fig’s painting thus, does not depict an actual event, bu t rather an imaginary one, showing the painter creating his own fiction. And indeed the image of Napolean on a horse does not synch up spatially with the image of Messonier, as if the artist has been superimposed upon his own painting. Fig here skillfully makes the point that any history contains more than a little fiction, no matter how convincingly rendered.

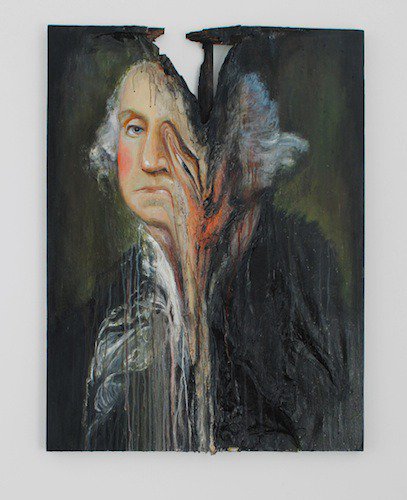

Blurring painting and sculpture, Valerie Hegarty makes reproductions of well-known historical paintings which she then dramatically alters so that they look as if they are disintegrating. In George 4, Hegarty takes Gilbert Stuart’s iconic portrait of Washington and causes it to melt, turning the President’s stoic expression into a frown. The tremendous critical reception to Hegarty’s recent work has interpreted it as a warning against imperial hubris or as a reminder that nothing, not even art lasts forever. She is included in this show to illustrate that trompe-l’oeil can be harnessed in many different ways. While Gilbert Stuart’s goal was to create an enduring image of a great leader, Hegarty points out that no matter how much symbolism the viewer may attach to the painting, it is only an image.

Steve Mumford has in many ways embraced the traditional role of the history painter, but in a manner that is entirely contemporary and relevant. He has made several trips to Iraq and was embedded with U.S. soldiers during combat missions in 2004. Mumford made on-the-spot observations in watercolor and pencil, working them up into larger oils in the studio. The monumental Battle in Baquba depicts a confrontation between American motorized troops and distant adversaries. Smoke, explosions and the gestures of the soldiers in the foreground convey both the excitement and horror of war. Mumford’s painting records the moment without idealization: the damaged, dusty landscape barely seems worth fighting for and the threat to the troops, while obvious, seems difficult to locate. Unlike earlier history painters who attempted to attach notions of nobility and purpose to their scenes, focusing on generals at key moments in deciding battles, Mumfor d harnesses the power of painting to a different purpose, acknowledging the thrill of battle but also its banality. While his work exhibits a fierce loyalty to the participants in the Iraq war, Mumford maintains an impartiality, a faithfulness to the actual events. In this way, he seems to affirm, rather than question painting’s ability to create an accurate historical document.

Image above: Valerie Hegarty, George Washington Melted 4, 2011, canvas, stretcher, acrylic paint, gel medium, 40 x 30 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Nicelle Beauchene Gallery, New York

Opening: Wednesday, July 11, 6 - 8 pm

Winkleman Gallery

637 West 27th Street, NY

Tues - Sat 11 - 6 pm

Admission free