Two exhibitions

dal 7/2/2013 al 20/4/2013

Segnalato da

Stephen G. Rhodes

Heidi Bucher

Thea Djordjadze

Berta Fischer

Loredana Sperini

Katja Strunz

Raphael Gygax

Judith Welter

7/2/2013

Two exhibitions

Migros Museum, Zurich

The sprawling installations of the American artist Stephen G. Rhodes combine a variety of media and are based on historical and cultural sources. He creates distinctive restless and elliptical systems in which he addresses issues such as repression and trauma. 'Collection on Display' presents selected works from the collection of the Museum bringing together works by Heidi Bucher, Thea Djordjadze, Berta Fischer, Loredana Sperini and Katja Strunz.

Stephen G.

Rhodes

The Law of the

Unknown Neighbor:

Inferno Romanticized

Curated by Raphael Gygax

The sprawling installations of the American artist Stephen G. Rhodes (b. Houston, Texas,

1977; lives and works in Berlin and New Orleans) combine a variety of media and are based

on historical and cultural sources. Rhodes creates distinctive restless and elliptical sys-

tems in which he addresses issues such as repression and trauma. The Migros Museum für

Gegenwartskunst presents The Law of the Unknown Neighbor: Inferno Romanticized, the

artist’s first solo show at a European art institution.

The visualization of history plays a central role in the work of Stephen G. Rhodes. His use of the “fac-

tual” amounts to a critical misappropriation—nothing is ever only about what it is about. For his in-

stallation The Law of the Unknown Neighbor: Inferno Romanticized, Rhodes draws on the famous “Lec-

ture on Serpent Ritual: A Travel Report” (also known as “Images from the Region of the Pueblo

Indians of North America”) Aby Warburg (1866–1929) delivered in 1923 at the Bellevue psychiatric hos-

pital in Kreuzlingen, where he was a patient. Warburg examined the serpent ritual of the Hopi in the

perspectives of art history, religious studies, and anthropology. His observations pay particular attention

to the serpent as a lightning symbol. Generalizing from the serpent as embodying the equivocation of

fear and reason, of deathly menace and healing power, Warburg develops the concept of an underlying

polarity that, he argues, is discernible in any symbol. But Rhodes is interested in more than just the

lecture’s content; he also considers its genesis and the historical context: in the late nineteenth cen-

tury—around the time of Warburg’s trip to the American southwest, where he attends the Hopi ser-

pent ritual as an observer—the expulsion and genocide of the native American population, which has

been going on throughout the nineteenth century, is gradually coming to an end. In 1921, Warburg,

suffering from a bipolar disorder, was compelled to repair to the Bellevue sanatorium in Kreuzlingen.

The psychiatrist Ludwig Binswanger believed that Warburg’s work on his scholarly endeavors had

“therapeutic potential” as part of his stay at the hospital; preparing the lecture, in particular, would be

a sort of “healing process.” Rhodes also explores Warburg’s “Library for the Study of Culture,”

which had to be relocated from Hamburg to London in 1933—shortly after Warburg’s death—to save

the books from the National Socialists. Rhodes’s interest in Warburg is not limited to the reconstruc-

tion of dates and facts, but is more comprehensive. The artist explains: “The biographical détournement

in this case is the subject of Aby Warburg. It has to be stated, first of all, that the subject I use of

course refers to Warburg, but it is a confabulation of the subject and his westward journey reimagined

from the sanatorium, and in turn my sanatorium. I am using the elliptical timeline charted out in

Warburg’s biography as the underlying grid for my associative drift. There are three events in Warburg’s

life that I seize upon to generate a formal structure: the Warburg library and its transference out of

Hamburg; Warburg’s American journey and escape to the Southwest; and his return to Binswanger’s

Bellevue sanatorium. The elliptical circulation of these events shapes an elusive triangle. They are

all formative moments and movements of refuge or transference.”

The Law of the Unknown Neighbor: Inferno Romanticized consists of a labyrinthine arrangement of fur-

niture objects such as hospital curtains and the shelves of a library. Rhodes also projects short

looped sequences onto walls and curtains—a form of presentation that may be seen as drawing on the

tradition of Expanded Cinema. As Rhodes puts it: “In my work, [the loop] extends [...] echoing in

some cases onto the two-dimensional works, and of course in the choreography of the narration and

citation, the storytelling.” The consequent lack of control and command on the artist’s part also

points to the issue of trauma, a central theme in Rhodes’s art. In the artist’s view, it constitutes a form

of historiography distinguished by its non-linear character. Last but not least, the expansive installa-

tion features flash sculptures that—as the flickering light emphasizes—are a reference to Walter De

Maria’s land art installation The Lightning Field (1977): 400 polished steel poles, each around eigh-

teen feet long, were arranged on a large piece of land that sees frequent thunderstorms. It is only when

a storm draws near and lightning actually strikes the poles that the sculpture is truly activated. As

Rhodes laconically notes, “I also think the impotence of The Lightning Field is fun—it’s an allegory for

the writing block Warburg as well as I myself suffer.”

Stephen G. Rhodes has presented his art in solo exhibitions at Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi (2012), Berlin,

the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles (2010), and elsewhere; in 2009, he contributed to the New Museum

Triennial, New York. The exhibition at the Migros Museum will be accompanied by the first monograph

about Stephen G. Rhodes; including essays by Raphael Gygax, Brian Price, John David Rhodes, Stephen

G. Rhodes, Laurence A. Rickels, and Keston Sutherland, it will be published by JRP|Ringier.

The exhibition is curated by Raphael Gygax (curator, Migros Museum für Gegenwartskunst).

Catalogue:

Stephen G. Rhodes: Apologies.

With contributions by Raphael

Gygax, Brian Price, John

David Rhodes, Stephen G.

Rhodes, Laurence A. Rickels

and Keston Sutherland.

English/German, 284 pages,

JRP|Ringier.

---

Collection

on Display:

Heidi Bucher, Thea Djordjadze,

Berta Fischer, Loredana Sperini,

Katja Strunz

curated by Judith Welter

Collection on Display presents selected works from the collection of the Migros Museum für

Gegenwartskunst. The first two presentations from the collection to be held in 2013 conti-

nue the exhibition cycle on contemporary sculptural praxis launched last year. The works by

Heidi Bucher, Thea Djordjadze, Berta Fischer, Loredana Sperini, and Katja Strunz on dis-

play in the second chapter of the exhibition examine the status of sculpture and the ways it

is perceived, and reflect the history and transformations of sculptural praxis.

In recent years, issues of sculpture have been a major focus of the exhibition programming at the

Migros Museum für Gegenwartskunst and the museum’s efforts to enlarge its collection. The three-

part presentation of works from the collection brings together works that raise questions concerning

the possibilities of sculptural production. As a genre, sculpture—whether figural or abstract—occup-

ied a central position in the history of art from the classical age to the modernist era. As the art his-

torian Rosalind Krauss has argued, since the onset of postmodernism, the conception of sculpture

has been expanded as its boundaries have become blurry—sculpture has quite literally been knocked

off its pedestal. Sculptural work has expanded into a variety of media and materials, exploring the

possibilities of space. The second chapter unites works distinguished by their critical engagement

with different materials and their specific connotations and potentials. The five artists whose works

will be on display in this chapter use fragile materials evincing traces of use, but also everyday stap-

les and organic matter, exploring their sculptural qualities.

The sculptures of Thea Djordjadze (b. 1971) are fragile arrangements of used objects such as buil-

ding materials and articles from the domestic sphere. She also often uses artifacts that carry speci-

fic cultural connotations (e.g., carpets). Djordjadze’s sculptural conglomerates form fragments that

gesture toward familiar everyday spatial elements or situations and their uses. At the same time, the

unfinished and raw surfaces and seemingly temporary arrangements of objects refer to sculptural

and architectural forms of classic modernism. Djordjadze usually conceives her works as site-speci-

fic, with reference to the local history and culture. The work Ohne Titel (2011), for example, was

created for the group show Melanchotopia initiated by the Witte de With, Rotterdam, which was held

at exhibition sites scattered all over the city: in existing empty display cases at the Groot Handelsge-

bouw, an old trading house built during the postwar boom years, Djordjadze installed various sculp-

tures made of painted glass panes that recalled the shapes of pieces of furniture. The sculpture

Place of His Disaffection (2011), a plaster-coated piece of foam padding, suggests a mattress. His

Vanity Requires No Response was made for the exhibition of the same title at the Contemporary Art

Museum, St. Louis. The work’s title quotes a line from the third section of T. S. Eliot’s epic poem The

Waste Land.

The works of the artist Katja Strunz (b. 1970) take up an avant-garde legacy, unfolding between a

formal constructivism and references to (post)modernist utopias. The principle of assemblage—

which is to say, the combination of different forms and materials—sustains a process that coalesces

into an overall appearance that may be read as illusionistic as well as abstract. The work Rheingold

(1998/2008) consists of an old rowboat that has disintegrated into fragments and stranded on an

abstract glass construction reminiscent of a lake. The simple formal vocabulary used to suggest an

abstraction of a landscape with boat evokes metaphorical and poetic images. Strunz pursues a

romanticized idea of land art as proposed by Robert Smithson’s sketches for crystalline and utopian

architectures, while the title, citing an opera by Richard Wagner, also gestures toward the spirit of a

mythical German romanticism.

The works of Loredana Sperini (b. 1970) similarly suggest associations of mythologies by staging

encounters between abstract and organic-figurative formal vocabularies. Arranged on a mirrored

surface is a stacked heap of branches, some of their ends coated in wax. Amid the dry wood, the

beholder espies casts of hands in colored wax. A recurrent central feature of Sperini’s art is experi-

mentation with different techniques and materials. The visual cosmos of the sculptural installation,

heightened by the contrasts between materials and forms, is paradigmatic of her oeuvre. She deve-

lops this cosmos in various media and employing highly time-consuming traditional manual tech-

niques that always also render forms of temporality visible. The artist came to renown primarily with

her kaleidoscopic web-like embroideries. In her more recent works, Sperini translates this abstract-

surreal and yet figurative visual language into wax and concrete reliefs and three-dimensional works

in space.

Berta Fischer’s (b. 1973) works examine questions of abstraction vis-à-vis a classic figurative motif.

By using fragile materials and delicate structures, Fischer explores the potential of formal creation

while calling its permanence in question. For years, the artist worked primarily in plexiglass and

other industrially prefabricated materials such as nylon threads and plastic foils. Fischer’s sculptures

may be read as a response to the rigid minimalism of the 1960s and 1970s, an art based on industrial

materials and dominated by emphatically male artists. Her sculptures made of neon-colored acrylic

glass address the transparency and fragility of this material, which is heightened by the incidence of

light. In the style of an “écriture automatique,” an unchecked stream of consciousness as envisioned

by the historic Surrealists, these fragile structures whirr through space and leave behind a frozen

image.

The artist Heidi Bucher (1926–1993) came to be known in the 1970s and 1980s for her latex skinnings

of architectures in space. No less central to her art is the engagement with the analogy between clo-

thes and the house as media of mental and historical remnants, as “vestments” that have the poten-

tial to preserve the psychological traces of wearers or residents. The cycle of works entitled Body

Shells (1972–1973) exemplifies the early period in the Swiss artist’s oeuvre. Working in Los Angeles

in collaboration with her then husband, Carl Bucher, she created sculptures out of foam material

whose outsides she daubed with mother-of-pearl, a material to which the artist would return again

later on. They are portable pieces that recall organic materials or strange sea creatures while also

being inspired by the futuristic fashion of the era. With her family, she staged a performance on the

beach at Venice Beach on which the film on display in the exhibition is based. The show also fea-

tures sketches with details executed in mother-of-pearl, preparatory works that document the deve-

lopment of the sculptures, as well as a set of latex objects.

Next chapter of the exhibition cycle:

May 4–August 18, 2013

Part 3: Valentin Carron, Manfred Pernice, Edward Krasiński, Stefan Burger

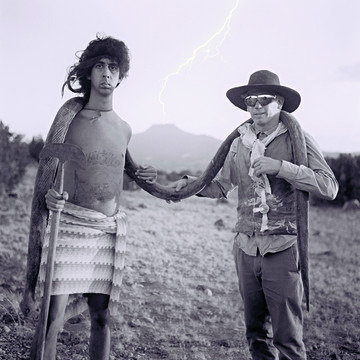

Image: Stephen G. Rhodes

Press:

For more information and

visual materials, please

contact René Müller, head of

press and public relations:

T +41 44 277 27 27 rene.mueller@mgb.ch

Media conference: February 8, 2013, 11 am

Migros Museum für Gegenwartskunst

Limmatstrasse 270 - 8005 Zürich

Opening hours

Tue, Wed, Fri 11 am – 6 pm

Thu 11 am – 8 pm

Sat, Sun 10 am – 5 pm

closed on Mondays

closed on December 24, 25 and 31 2012

December 26, 2012 10 am – 5 pm

Maundy Thursday 11 am – 8 pm

Good Friday until Easter Day 10 – 5 pm

Ascension Day, Whit Monday, May 1 10 – 5 pm

Admission

Adults: SFR 12

Reduced: SFR 8

Free admission for pupils and young people under 16 years.

Groups of 10 or more people

Guided tours:

SFR 160 + admission, during our opening hours

SFR 280 + admission, outside our opening hours

The Swiss Museum Pass is not valid at the Migros Museum für Gegenwartskunst.