Jane Stravs

dal 13/2/2013 al 22/3/2013

Segnalato da

13/2/2013

Jane Stravs

Galerija Fotografija, Ljubljana

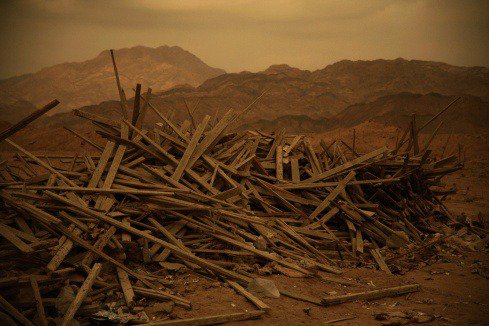

Dahab. The photographs construct boundaries within the landscapes of Dahab that have already been remodeled anyway before the photographs were taken by political, economic and social forces there.

The major characteristic of Jane Štravs’ photographic work is certain logic of subversiveness, a logic of extraction, or even more, of subtraction (as the French philosopher Alain Badiou calls this mathematical operation of less producing more and that is aesthetical in the end), in order to organize the photographs as less so as to fuel more desire, a desire to see and to know more.

We know nothing about Dahab without a text, but are so intrigued after seeing the photographs of Dahab by Štravs as to search for more. Dahab, a Bedouin fishing village situated on the southeast coast of the Sinai Peninsula in Egypt, approximately 80 km northeast of Sharm el-Sheikh, is considered to be one of the Sinai’s most treasured diving destinations.

The Bedouins have ever been there, but today, so are the international hotel chains and other facilities that have transformed Dahab into a popular destination for tourists. The word Dahab is Arabic for gold and is possibly a reference to the geographic locality of Dahab. The color of gold in the photographs comes from the sand washed down from the mountains in the desert and accumulated by the alluvial floods in the south of the village. Therefore, the name Dahab stems from the floods that wash through the town every five or six years. Caused by larger than average storms in the mountains, the flood waters surge down to the sea carrying with it great amounts of sand.

The photographs of Štravs are negotiating precisely such a landscape of Dahab. It is better to say that the photographs construct boundaries within the landscapes of Dahab that have already been remodeled anyway before the photographs were taken by political, economic and social forces there. The Dahab landscape is the landscape of Bedouin men, women and children, migrants from the urban centers as well, and last but not least, the tourists.

The view by Štravs stops the flux of bodies and landscape while interacting with the imagination of us here and intervening in the possible perception of the people and places by us, the viewers, there. Tourism is present, though not present in the images, for we suspect that the eye of the photographer is that of the tourist; we see that what is in front of us is an interior, as the beach is left out of the gaze.

The interior and the roads (without the beach) build a dynamic and interactive set of relationships that take place in between and across them. As noted by Heba Aziz, the incursion of newcomers represented by Egyptian migrant labor, investors and tourists change the landscape. The landscape in the photographs is about internal relations in Dahab, and therefore we have to ask the question: Whom do we see on the road and in the landscape?

We have to ask how these relations, of the interior of Dahab and of the exterior of Dahab (the beach), are negotiated. Who, if any, are the visible figures in the landscape? How have the passage from the private to the public domain and the boundary from passive to active landscapes been re-constructed and then recorded by Štravs’ photographs? He also exposes in these series cultural contradictions, social hierarchies and empowerment, three main points of his photographic thinking in general.

Štravs’ photographs are an interstice between realities. This results in a division between the ordinary and the extraordinary that involves experiences of time and space different from those normally encountered in daily life. Every space has a history and every history is material and discursive at once. Štravs once again, but this time in another geopolitical frame, examines the boundaries of traditional landscape.

He reveals influences of continuity and change in social structures within photography, especially in terms of gender and social status codes, visibility and invisibility. These codes impose precise spatial regulations and narrations, and Štravs asks: Who owns the codes of photography? Who stores them? How can we subvert them? These are topics that have a long history within his work.

What does a Western European gaze capture regarding the formation of social identities?

In the age of technologically, and more precisely digitally, produced images, the problematic status of photography can be precisely captured by insisting on a gap that exists between the concept of photography to present a true understanding of the world and a photograph that produces a more or less accurate rendering of represented objects, figures and bodies. What role does the photographer play in this shift from photography as a supposedly objective eye toward photography being a powerful aesthetical practice? More specifically, what is the camera’s contribution to the development of highly ideological photographic sequences?

Photographs of Dahab are arranged along the spectrum that extends them between still images and motion pictures. What we see here in Štravs’ photographic series of Dahab is an inversion of the common relation of the real and the imaginary, where the bodies are more or less always real and the landscape is imaginary – yet here, the landscape is provocatively real, while a body is stubbornly imaginary.

Opening: 14 February at 7pm

Galerija Fotografija

Mestni trg 11/I, Ljubljana

Hours: tuesday - friday: 12h- 19h,

saturday: 10.00 – 14.00

Free Admission