Two exhibitions

dal 4/3/2013 al 11/8/2013

Segnalato da

4/3/2013

Two exhibitions

The Museum of Modern Art - MoMA, New York

"Structure Brought to Light" by Henri Labrouste presents over 200 original drawings, vintage and modern photographs, films and architectural models. Labrouste (1801-1875) had a dramatic impact on 19th-century architecture through his explorations of new paradigms of space, materials, and luminosity. Bill Brandt (1904-83) is a founding figure in photography's modernist traditions, on view more than 150 works divided into 6 sections: London in the Thirties; Northern England; World War II; Portraits; Landscapes; and Nudes.

Bill Brandt

Shadow and Light

The Robert and Joyce Menschel Photography Gallery and The Edward Steichen Photography

Galleries, third floor

The Museum of Modern Art presents Bill Brandt: Shadow and

Light, a major critical reevaluation of the heralded career of Bill Brandt (British, b. Germany,

1904-83) from March 6 to August 12, 2013. A founding figure in photography’s modernist

traditions, Brandt ranks among the visionaries who, in the diversity of their approach, established

the creative potential of photography based on observation of the world around them. Brandt’s

distinctive vision—his ability to present the mundane world as fresh and strange—emerged in

London in the 1930s, and drew from his time in the Paris studio of Man Ray. His visual

explorations of the society, landscape, and literature of England are indispensable to any

understanding of photographic history and, arguably, to our understanding of life in Britain during

the middle of the 20th century.

Bill Brandt: Shadow and Light is organized by Sarah Meister,

Curator, with Drew Sawyer, Beaumont and Nancy Newhall Curatorial Fellow, Department of

Photography.

The impressive breadth of Brandt’s career, which suggests his restless experimental

impulse, and the dramatic transformations of his printing style have often confounded those

seeking to understand the link between the highly celebrated and seemingly unrelated chapters of

his oeuvre. The exhibition brings together more than 150 works divided into six sections, each

corresponding with a distinct aspect of Brandt’s achievement: London in the Thirties; Northern

England; World War II; Portraits; Landscapes; and Nudes.

Beginning with a highly selective

display of albums and prints made around the European continent as Brandt was forming his

artistic identity, the exhibition presents an opportunity to understand Brandt in a new light: one

that establishes a chronological trajectory of his career, with an expanded consideration of his

activity during World War II.

In addition, a closer look at his printing methods with the finest

known prints from across the range of Brandt’s career will clarify how the artist, whose early work

is characterized by the muted, wistful portrait of a young housewife scrubbing the threshold to her

home (East End Morning, 1937), would come to create a bold and unpredictable series of nudes

on the rocky English coast (East Sussex Coast, 1957).

Brandt established his reputation before the Second World War with the publication of The

English at Home (1936) and A Night in London (1938), books that distilled his early photographic

studies of life in Britain. Noted works from this period on view include: Parlourmaid Preparing a

Bath before Dinner (c. 1936); Soho Bedroom (1934); Street Scene, London (1936); and Losing at

the Horse Races, Auteuil, Paris (c. 1932), which Brandt later re-titled Racegoers in Sandown Park

in order to present it in the context of his English pictures, an expression of his disdain for slavish

adherence to facts.

During this same period, Brandt ventured to several industrial towns in northern England

to witness firsthand the impact of the Depression. Striking images from this group, including A

Snicket in Halifax (1937), Coal-Searcher Coming Home from Jarrow (1937), and Northumbrian

Miner at His Evening Meal (1937), bear unequivocal witness to the devastating unemployment

that plagued the region at the time, but there is a subtle ambiguity to many of these images that

suggests Brandt found the artistic potential of these soot-blackened structures and faces

competing for his attention.

Brandt’s activity during the Second World War—long distilled by Brandt and others to a

handful of now-iconic pictures of moonlit London during the Blackout and improvised shelters

during the Blitz—are presented for the first time in the context of his assignments for the leading

illustrated magazines of his day, establishing a key link between his pre- and postwar work. In

addition to photographs such as Liverpool Street Underground Station Shelter (1940) and

Deserted Street in Bloomsbury (1942), this section includes lesser-known works from the period

such as: Bombed Regency Staircase, Upper Brook Street, Mayfair (c. 1942); Packaging Post for

the War (c. 1942); and a suite of extraordinary wartime portraits.

Brandt’s assignments for Picture Post and Lilliput magazines, as well as Harper’s Bazaar

(UK and US), led variously into extended investigations of portraiture and landscape photography,

with a strong emphasis on contemporary literary figures in Britain and the country’s rich literary

heritage. A solemn, vaguely distracted expression became a hallmark of Brandt’s portraiture, and

notable examples on view include Dylan Thomas, Norman Douglas, Evelyn Waugh, Reg Butler,

Harold Pinter, Martin Amis, Tom Stoppard, Vanessa Redgrave, Barbara Hepworth, Henry Moore,

and Francis Bacon.

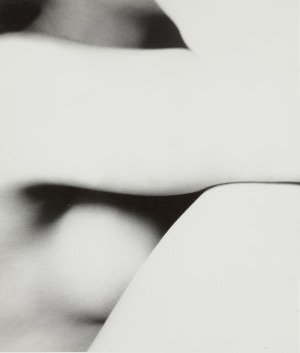

Brandt’s crowning artistic achievement—published as Perspective of Nudes in 1961—is a

series that is both personal and universal, sensual and strange, collectively exemplifying the

“sense of wonder”, to quote Brandt, that is paramount in his photographs. His extended

investigation of the female nude remains his most original and memorable work, defying

preconceived notions of the genre with his choice of settings (inhospitably barren seashores or

prim Victorian interiors that conflated the domestic and the sexual in lieu of sterile, but safe,

studios), as well as the extreme exaggeration of his distortions, cropping, and printing styles,

rendering what might otherwise have been hopelessly clichéd aspects of the female form

unfamiliar and surprising. On view are over 40 photographs from this period, including four prints

of his iconic London (1952), which together suggest Brandt’s willingness to reinterpret even the

most supremely resolved images in his oeuvre.

Through a rigorous analysis of each chapter of Brandt’s career across a half century of

work, the exhibition clarifies the achievement of this towering figure in photography’s modernist

tradition.

Published in conjunction with the exhibition, Bill Brandt: Shadow and Light presents the

photographer’s entire oeuvre, with special emphasis on his investigation of English life in the

1930s and his innovative late nudes. Rich tritone illustrations highlight the special characteristics

of Brandt’s prints, and an essay by curator Sarah Hermanson Meister sets Brandt’s life and work

in the context of 20th-century photographic history. Lee Ann Daffner, the Museum’s Andrew W.

Mellon Foundation Conservator of Photographs, contributes an illustrated glossary of Brandt’s

retouching techniques, enhancing the appreciation of his printing processes. The book also

includes a generously illustrated appendix of Brandt’s photo-stories published during the Second

World War, clarifying the photographer’s career as never before. 9”w x 10.5”h; 208 pages; 254

tritone illustrations. Hardcover, $50. Published by The Museum of Modern Art and available in

March at MoMA Stores and online at MoMAStore.org. Available to the trade through ARTBOOK |

D.A.P. in the United States and Canada. Published and distributed by Thames & Hudson outside

the United States and Canada.

Major support for the exhibition is provided by GRoW Annenberg/Annenberg Foundation, The

Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, Heidi and Richard Rieger, Ronit and William Berkman, and by

Peter Schub, in honor of Anne and Joel Ehrenkranz. Research and travel support provided by The

International Council of The Museum of Modern Art.

Additional generous funding for the publication was provided by the John Szarkowski Publications

Fund.

-------

Henri Labrouste

Structure Brought to Light

March 5–June 24, 2013

Henri Labrouste: Structure Brought to Light, the first solo

exhibition of Labrouste’s work in the United States, highlights his work as a key milestone in the

evolution of modern architecture, libraries in particular. The exhibition is on view from March 10 to

June 24, 2013. Over 200 works, from original drawings—many of them watercolors of haunting

beauty and precision—to vintage and modern photographs, films, and architectural models

illustrate the power of his works, the uniqueness of their decorative details and the prominence he

gave to new materials, in particular to iron and cast iron.

The exhibition is organized by Barry Bergdoll, The Philip Johnson Chief Curator of Architecture and Design, The Museum of Modern Art;

Corinne Bélier, chief curator, Cité de l’architecture & du patrimoine; and Marc Le Cœur, art

historian, Bibliothèque nationale de France, département des Estampes et de la photographie.

Henri Labrouste: Structure Brought to Light is presented by MoMA, the Cité de l’architecture & du

patrimoine, and the Bibliothèque nationale de France, with the participation of the Académie

d’architecture and the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève.

Henri Labrouste (French, 1801–1875) had a dramatic impact on 19th-century architecture

through his explorations of new paradigms of space, materials, and luminosity in unprecedented

places of great public assembly. His two magisterial glass-and-iron reading rooms in two Parisian

libraries—the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève (1838–50) and the Bibliothèque nationale (1859–

75)—gave form to the idea of the modern library as a machine for knowledge and a space for

contemplation. Labrouste also sought a redefinition of architecture by blending art and

constructive innovation with new materials and new building technologies. His spaces are

overwhelming in the daring modernity of their exposed metal frameworks, exquisitely and

austerely detailed masonry walls rethought for the age of iron construction, new mechanical

systems and forms of heating, and stunning luminosity, using gas lighting to create spaces that

are immersive and timeless. The exhibition concludes with an examination of Labrouste’s diverse

and extensive influence, from his students and early followers to contemporary practitioners.

Henri Labrouste: Structure Brought to Light is divided into three sections: The Romantic

Imagination; Spaces of Knowledge; and Prosperity and Affinities.

The Romantic Imagination

The exhibition’s first section covers the period from 1818, the start of Labrouste’s artistic

training, to 1838, tracing the development of Labrouste’s philosophy of architecture and practice

in two settings—ancient Rome and modernizing Paris—which Labrouste conceived of as

architectural laboratories. During the five years Labrouste spent at the French Academy in Rome,

he began to explore a notion of architecture as the product of layers of history, societies in

evolution, and of historical change, and he proposed a new approach to architecture’s capacity to

carry social meaning.

On his return to Paris, Labrouste initially focused on the ephemeral architecture of public

ceremonies. With their ability to temporarily rewrite the experience of the city, Labrouste saw

them as fundamental in finding an architecture of social relevance for modernity. During this time,

Labrouste directed the Return of the Ashes of Napoleon I in December 1840, proposed a project

for the imperial tomb in the church of Les Invalides, and won two important international

competitions for the construction of an insane asylum in Lausanne and a prison in Alexandria,

near Turin. Drawings of these unbuilt but influential projects are included in the exhibition.

This section is punctuated with some of Labrouste’s most beautiful works, measured

drawings and reveries on the diverse architectural and daily landscape of Italy, both ancient and

modern. These include drawings and studies of ancient monuments and Etruscan tombs that had

just been discovered in the early 1800s, and of urban compositions, as seen in his hypothetical

reconstruction of an ancient city and in a projected reconstruction of the ancient port at Antium

(modern Anzio). These studies illustrate Labrouste’s methods and the uniqueness of his approach,

which would later characterize his particular architectural style—great attention to the relationship

of the forms of architecture to changes in building materials and methods, fascination with the

evolution of permanent ornaments from festivals and ceremonies, and an interest in the

coexistence of different historical periods. This relativism and progressive vision of history—

framed in the very years in which the term avant-garde first was employed as a term of artistic

strategy—would lead to Labrouste to being considered part of the romantic architectural

movement that eventually rallied a new generation of architects in 1830.

Spaces of Knowledge

The second part of the exhibition is devoted to Labrouste’s principal works as a public

architect in the period of Paris’s great urban transformation in the mid-19th century, most notably

two remarkable libraries: the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève (1838—1850), and the restoration

and extension of the Bibliothèque nationale de France (1854—1875). In each of these projects,

Labrouoste deployed novel materials and techniques of both construction and information storage

and retrieval. He also sought to create an immersive environment of study and reflection in the

midst of the city. The buildings were admired as much for their efficient solutions to the issues of

nascent library science—including layout, flow of readers and books, and space and light, but also

for their creation of veritable monuments to the role of knowledge and information in modern

society. The vaulted reading rooms of the two libraries were astonishing for their lightness of

structure and luminosity, and for the creation of exalted spaces for large groups of students and

readers to work individually, yet in a group setting. These buildings, among the most

extraordinary spatial creations in European architecture, have been touchstones for library design

ever since.

More than any architect at the time, Labrouste was able to make the most of pre-existing

urban and historical surroundings. The monumental Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève connects in

this way with the neighboring Panthéon as the first self-contained public library fitted out within

an ornate structure. Its facades are mainly decorated with a seemingly endless list of names that,

forming a catalog of writers and leaders in all domains of intellectual pursuit, coalesce into a

symbolic history of mankind’s intellectual progress. The inscribed names clearly display the

purpose of the structure in making writing itself a means of public ornament on the great plaza of

Sainte-Geneviève. Inside, the abundant use of industrial materials (iron and cast-iron), the quality

of the inner spaces and interior decoration, and the use of gas lighting (making the Bibliothèque

Sainte-Geneviève the first library that could admit readers in the evening), were revolutionary

achievements at the time.

The restoration and extension of the Bibliothèque nationale de France developed the

solutions used by Labrouste at the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève. His penchant for the

combination of iron, cast iron, and light are noticeable, as are the meaningful decorative details,

but in a very different context. As a result, the reading room in the Bibliothèque nationale de

France—a great square room composed of nine square domed bays crowned by ceramic vaults

held aloft by four slim 33-foot-high columns—is one of the most dazzling yet reposeful expressions

of the new possibilities of iron construction in modern architecture. Where the upper walls could

not be pierced to maximize daylight, Labrouste had painted landscapes of trees, simulating a

peaceful garden setting to create a calm ambience for study in a space at once vast and intimate.

In contrast to the ornamented structure of the reading room, the great central book stacks,

visible through a monumental archway, were entirely conceived in functionalist iron expression, in

everything from the superstructure of the stacks, sky-lit from above, to the shelves, walkways

and staircases, all pierced to allow natural light to penetrate through five levels of book storage. A

pneumatic tube system serviced this area to assure rapid delivery of books from stacks to

readers, a process library visitors could glimpse through a great wall of glass separating the

reading room from the stacks.

The evolution of these two designs is documented in Labrouste’s own exquisite drawings of

everything from the cutting of the masonry, to the ornamentation of the iron members of the

vaults, to the handling of the bookcases and the purpose-designed furniture for these rooms. The

building contractor drawings for the realization of the novel iron framework of the nine cupolas of

the Bibliothèque nationale de France’s reading room are on view as well, alongside newly made

analytical models, historical photographs, and modern large-scale projections of the two reading

rooms, including one that simulates the effects of gas lighting in the Bibliothèque Sainte-

Geneviève.

Labrouste’s explorations of architecture for collective purposes are also shown in a small

number of lesser known but influential buildings, such as the seminary of Rennes (1854—1875).

Prosperity and Affinities

The exhibition’s final section traces Labrouste’s extensive and varied influence on his peers

and subsequent generations both through many decades of teaching but mostly through the

example and wide acclaim of his two libraries. His students worked throughout France, and key

figures emigrated to the United States, the Netherlands, Turkey, and Peru. Henri Labrouste:

Structure Brought to Light presents the works of several of Labrouste’s students, such as Juste

Lisch (1828—1910), and Gabriel Toudouze (1811—1854), as well as a few of the buildings

constructed later on by former students of Labrouste: the Library of the Law School of the

University of Paris, one of the great losses of the 1960s, designed by Louis-Ernest Lheureux

(1827—1898), schools by Charles Le Cœur and the Parisian Post Office by Julien Guadet (1834—

1908)—buildings that were markedly influenced by Labrouste’s teaching and practices.

The influence of Labrouste can also be seen in the development of metallic architecture,

particularly in the mid-19th-century dream project of the Great Hall of Public Assembly. The

exhibition juxtaposes Labrouste’s designs with other projects by leading architects—such as the

work of E.E. Viollet-le-Duc, designs for a monumental church made entirely of prefabricated metal

elements by Louis Boileau, and a project for roofing Parisian boulevards in iron and glass by

Hector Horeau, and a series of built works in the last decades of the 19th century, notably the

work of Jules André, who was Labrouste's inspector on the construction site of the Bibliothèque

nationale de France and who succeeded him at the head of his workshop before designing the

extraordinary gallery of Zoology at the Museum of Natural History, in Paris.

After examining the impact of Labrouste's works abroad, particularly in the area of libraries,

the exhibition continues with work by an international array of architects, including Labrouste’s

pupils and followers in France, the Netherlands, and the United States. In addition to well-known

designs such as the Lenox Library, in New York, or the Boston Public Library, the influence of

Labrouste in key projects of important but lesser-known American architects, such as Henry

Hornbostel (designer of numerous New York City bridges) are shown. (Of special note is

Hornbostel’s great library in the State Education Building, in Albany, NY.) Projects with more

distant echoes of inspiring work, by architects such as Louis Sullivan, Frank Lloyd Wright, and Pier

Luigi Nervi, are also featured. A series of filmed interviews with contemporary practitioners,

including the French architect Manuelle Gautrand, who discuss Labrouste’s legacy and immensely

rich body of work, concludes the exhibition.

Published in conjunction with the first exhibition devoted to Labrouste in the United States—and

the first anywhere in the world in nearly 40 years—Henri Labrouste: Structure Brought to

Light is the result of a four-year research project into the entirety of Labrouste’s production. The

volume presents nearly 225 works in a variety of mediums, including drawings, watercolors,

vintage and modern photographs, film stills, and architectural models. Essays by a range of

international architecture scholars explore Labrouste’s work and legacy, offering fresh historical

perspectives on the architect and his structural innovations. 9.5′′w x 11.75′′h; 232 pages; 225

color illustrations. Hardcover, $55. Published by The Museum of Modern Art in conjunction with

the Cité del’architecture & du patrimoine, Paris, and the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Available in March at the MoMA Stores and online at MoMAstore.org. Available to the trade

through ARTBOOK | D.A.P. in the United States and Canada, and through Thames & Hudson

outside the United States and Canada. Henri Labrouste: Structure Brought to Light is edited by

Barry Bergdoll, Corinne Bélier, and Marc le Coeur, with essays by Neil Levine, David van Zanten,

Martin Bressani, Sigrid de Jong, Bertrand Lemoine, and Marie-Hélène de la Mure.

Henri Labrouste: Structure Brought to Light is presented by MoMA, the Cité de l’architecture & du

patrimoine, and the Bibliothèque nationale de France, with the participation of the Académie

d’architecture and the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève.

The exhibition is supported by The International Council of The Museum of Modern Art, Cetie

Nippert Ames and Anthony Ames, and the French Heritage Society.

PUBLIC PROGRAM:

Revisiting Henri Labrouste in the Digital Age: A Symposium

Thursday, March 28, 2013, 10:00 a.m.–5:00 p.m.

Theater 3 (The Celeste Bartos Theater), mezzanine, The Lewis B. and Dorothy Cullman Education

and Research Building

Held in conjunction with the exhibition Henri Labrouste: Structure Brought to Light, this

symposium acts, in part, as the fourth section of the three-part exhibition. It explores how a 19th-

century architect and his work, and particularly his innovative use of materials and light in spaces

of contemplation and public assembly, are relevant in contemporary culture and architecture.

Young and mid-career architects and scholars examine Labrouste’s inclusion in a 1975 exhibition

at MoMA and how today’s context is different; and how issues such as the library in the

information age, the collective expression of individual experience, and the rational ornament

apply to contemporary practice.

Tickets ($12, $8 members and corporate members, $5 students, seniors and staff of other

museums) can be purchased online or at the information desk in the main lobby, the film desk or

in the Education and Research Building lobby on the day of the program.

No. 8

----

Simone Forti: King's Fool

March 6 and 7, 3:00 p.m.; March 8, 5:00 p.m.

The Michael Ovitz Family Gallery, fourth floor

For the last installment of MoMA's performance series Performing Histories: Live Artworks Examining the Past, the Museum presents King's Fool by Los Angeles-based artist Simone Forti. One of several key figures of the 1960s minimalist dance movement, Forti defined a new language of physical movement. In this new work, premiering at MoMA, Forti draws on one of her ongoing projects, News Animations, which was initially developed in the 1980s. In News Animations the news become the choreographer, determining Forti's movements and speech—the imagery and language of newspaper reports and newscasts are translated into improvised movement compositions. Moving and speaking become a method of social commentary and inquiry, "activating" all of the words that come to the artist's mind during the performance. Thus in King's Fool patterns of language, and the body in motion, play off one another, sparking questions. Silences, speculation, and personal experience interweave with the flickering, fluid vision of the world brought to us by the news media.

----

Image: Bill Brandt, London, 1954

Press Contact:

Paul Jackson, (212) 708-9593, paul_jackson@moma.org

Margaret Doyle, (212) 408-6400, margaret_doyle@moma.org

Press Viewing: Tuesday, March 5, 10:00 a.m. to 12:00 p.m.

The Museum of Modern Art, MoMA

11 West 53 Street, New York, NY 10019

Hours: Wednesday through Monday, 10:30 a.m.–5:30 p.m. Friday, 10:30 a.m.–8:00 p.m. Closed Tuesday.

Museum Admission: $25 adults; $18 seniors, 65 years and over with I.D.; $14 full-time students with

current I.D. Free, members and children 16 and under. (Includes admittance to Museum galleries and film

programs).