Mel Bochner

dal 5/3/2013 al 22/6/2013

Segnalato da

5/3/2013

Mel Bochner

Haus der Kunst, Munich

If the Color Changes. As a founding figure of Conceptual Art, it is astonishing that Bochner used color not only sporadically, but with consistent regularity. In fact, in his more recent work, color has shifted into the foreground and seems to compete with language and text at the highest level.

curated by Achim Borchardt-Hume, Head of Exhibitions at

Tate Modern, London (previously Chief Curator,

Whitechapel Gallery) and Dr Ulrich Wilmes, Chief

Curator at Haus der Kunst

Mel Bochner (born in 1940 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania) is

considered one of the founders of Conceptual Art, which, in the

early 1960s, surpassed painting as the primary art form. Bochner

achieved this feat in part by using language in his works. In his

more recent work, he has increasingly re-examined this once-

despised medium of painting, whereby his own conceptual visual

language contributes insights of its possibilities. The artist's

first solo exhibition in Germany in more than 15 years

(Lenbachhaus 1996), the show at Haus der Kunst illustrates the

relationships between Bochner's use of text and color in the 1960s

and 1970s, and his often painterly work created during the past

decade. It includes a variety of media, from sculpture, drawings,

installation, murals, to photographs, and paintings on canvas.

Bochner's first solo exhibition took place in 1966 in the gallery

of the School of Visual Arts in New York, where he worked as an

assistant professor of art history. In the show he presented four

identical three-ring binders on pedestals. Each contained 100

copies of various working drawings and sketches. Some of these

works were created by artist friends, such as Donald Judd, Dan

Flavin, Sol LeWitt, Eva Hesse and Robert Smithson, as well as

several scientists, whom Bochner had asked to contribute pieces to

an exhibition on 'work trials'. Because the show's organizers

lacked the funds to frame the works, Bochner made photocopies of

them and arranged them alphabetically in the binders. Titled

"Working Drawings and Other Visible Things on Paper Not

Necessarily Meant to Be Viewed as Art" (1966), Bochner invited the

show's visitors to leaf through the works and become active

readers rather than simply passive observers. At the same time, he

redefined the term 'authorship': Although he served as exhibition

curator, he also transformed the show into his own artwork. The

artists, to whom he had returned the originals before the opening,

welcomed this idea. Only Donald Judd was irritated by Bochner's

appropriation. The exhibition is considered the first show of

Conceptual Art, and was pioneering for the art form's development.

At the time, the artist was also exploring the idea of

reproduction and transformation in the field of photography. "36

Photographs and 12 Diagrams" (1966/2003) is based on twelve

diagrams consisting of seven times seven boxes in squares and

marked with the numbers one to four. The numbers represent the

number of stacked wooden blocks that Bochner rearranged repeatedly

according to the diagrams. He had the figures professionally

photographed, thereby creating a documentation of the figures as

top views, elevations, and from bird's-eye perspectives. Through

the interplay of drawn diagrams and their photographic

equivalents, Bochner demonstrated how the photographs were limited

in their ability to unite perspective accuracy and illustrate

complex issues. This project was the first in a series of

experimental photographic works that explored color, texture, and

lighting conditions; others included "Transparent and Opaque"

(1968/2008) as well as objects, such as "Color Crumple" (1967).

As he did with photography, the artist also set his conceptual

sights on painting. One of his most famous works is "A Theory of

Painting" (1969-70), a floor work inspired by Henry Matisse and

Jackson Pollock, a new installation of which he will create for

Haus der Kunst using pages from a current edition of the

"Süddeutsche Zeitung" (a German newspaper). The work consists of

four identical areas - covered with newspaper pages of a

particular edition of which the outer two create clearly defined

rectangles and the inner two, formed by crisscrossing sheets of

paper, loosely suggest rectangular forms. All four rectangles are

spray-painted blue: A closed colored rectangle covers both an

outer and inner rectangle and a fragmented rectangular shape is

situated on the other two rectangles. In this way, the figure-

ground relationship is depicted in four versions. A wall

inscription summarizes this gimmick in concrete words Cohere –

Disperse, Disperse – Cohere, Disperse – Disperse, Cohere – Cohere.

Early in his career, Bochner also explored mathematics. He was

particularly interested in number series and geometrical forms

with which he experimented in drawings and floor installations

consisting of stones, colored glass and chalk, creating random

patterns in the process. In "Meditation on the Theorem of

Pythagoras" (1972/2010), he examined the theorem. Using chalk, he

drew a right-angled triangle on the floor and, using stones,

arranged a square on each side, out of 5 x 5, 4 x 4 and 3 x 3

glass stones. According to the sum of the equation, a2 + b2 = c2,

the number of stones should be 50 but it was, in fact, only 47.

Bochner countered an intellectual puzzle, which could probably

have been easily solved, with a visual experience to shift the

viewers' attention away from the geometry and on to the sensuality

of color. He also explores the relevance of mathematical

principals and measurements in "If/And/Either/Both (Or)" and

"Event Horizon" (both from 1998).

As a founding figure of Conceptual Art, it is astonishing that

Bochner used color not only sporadically, but with consistent

regularity. In fact, in his more recent work, color has shifted

into the foreground and seems to compete with language and text at

the highest level. The Thesaurus Paintings series displays word

chains on large-format canvases, reminiscent of accurately

executed busywork. Brightly painted letters compete with an

equally colorful background and demand that the viewer both read

and observe. Bochner calls this "the conflict between color as a

color perception and as grammar". These painterly works are

influenced by Bochner's word portraits from the 1960s in which he

embellished the work of artist friends like Sol LeWitt and Eva

Hesse with word chains. In his more recent works, he boldly unites

color and text to challenge the viewer both visually and

intellectually. Words to decipher include the following:

"AMAZING! AWESOME! BREATHTAKING! HEARTSTOPPING! MIND BLOWING! OUT-

OFSIGHT! COOL! WOW! GROOVY! CRAZY! KILLER! BITCHIN'! BAD! RAD!

GNARLY! DA BOMB! SHUT UP! OMG! YESSS!"

Rather harmless and traditional exclamations are gradually

transformed into modern, colloquial expressions, which can be

found in contemporary synonym dictionaries. The garish colors of

the letters and the lined background act as an visual amplifier

for the expressions, but, after prolonged observation, these jump

into the foreground so that the text is in danger of being

swallowed up by color; the message sinks into the sensory

overload.

In the series "If the Color Changes" (1997-2000) Bochner quotes

from one of Ludwig Wittgenstein's treatises on color: "Viewing is

not the same as observing or looking (...) If the color changes,

then you are no longer seeing what I meant (...)." While the

philosopher engaged in various theoretical visual processes,

Bochner translates Wittgenstein's texts into a painterly concept.

He overlaps the original passage with its English translation to

force the viewer to actively observe the complex text-image,

leading him or her to question its meaning.

In "The Joys of Yiddish" (2006), color and text are also closely

linked. Bochner originally designed the two-color banner for the

Spertus Institute of Jewish Studies in Chicago. The over-size work

will be installed on the façade of Haus der Kunst for this

exhibition. The word chain contains Yiddish slang words that have

found their way into contemporary American English. These include.

KIBBITZER, KUNI LEMMEL, DREYKOP, ALTER KOCKER, MESHUGENER, PISHER

(wise guy, simpleton, scatterbrain, geezer, crackpot, brat). The

banner's colors – yellow on black – are reminiscent of the

armbands and patches used by the Nazis to stigmatize the Jewish

population. There is an inherent tension between them and the

words residents in the Jewish ghettos used to express their unity

and defiance during the Third Reich. This connection between the

offenders' color and the victims' language is typical of the

subtle provocation that runs through Bochner's work.

The exhibition is organized by Whitechapel Gallery, London in

collaboration with Haus der Kunst, Munich and Museu de Arte

Contemporânea de Serralves, Porto.

Catalogue Published by Hirmer; with contributions by Achim

Borchardt-Hume, Briony Fer, Ulrich Wilmes, Mark

Godfrey, João Fernandes and Mel Bochner; ISBN

978-3-7774-8011-4, 214 pages, 168 illustrations,

24.5 x 28.5 cm, soft cover, 30 €

Next venue Museu de Arte Contemporânea de Serralves,

Porto, Portugal, July 12 – October 13, 2013

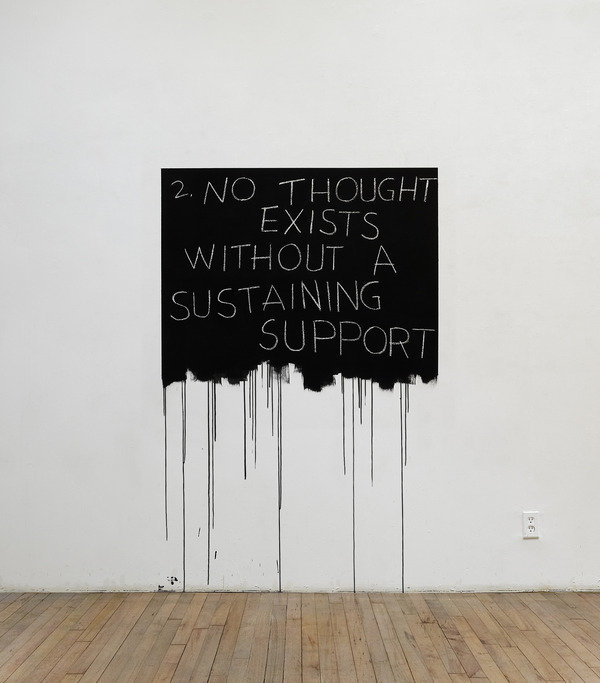

Image: Mel Bochner, No Thought Exists Without A Sustaining Support, 1970. Acrylic and chalk on wall, 182.9 x 121.9 cm. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, bequest of J.D. Zellerbach, by exchange, 2009.84 © Mel Bochner

PRESS

PRINZREGENTENSTRASSE 1

80538 MUNICH

+49 89 21127 115

+49 89 21127 157 FAX

PRESSE @ HAUSDERKUNST.DE

Press Viewing Wednesday, March 6, 2013, 11 am

Opening Wednesday, March 6, 2013, 7 pm

Haus der Kunst

Prinzregentenstrasse 1 - 80538

Opening Hours Mon — Sun 10 am — 8 pm, Thu 10 am — 10 pm

Admission 8 € / reduced rate 6 €

under 18 2 € / children under 12 free

Combined ticket 2 exhibitions 12 € / reduced rate 10 €

3 exhibitions 15 € / reduced rate 12 €