Sigmar Polke: 1963-2010

dal 8/4/2014 al 2/8/2014

Segnalato da

8/4/2014

Sigmar Polke: 1963-2010

The Museum of Modern Art - MoMA, New York

Alibis. The artist elided conventional distinctions between high and low culture, figuration and abstraction, and the heroic and the banal in works ranging in size from intimate notebooks to monumental paintings. The first comprehensive retrospective, encompassing his work across all mediums, including painting, photography, film, drawing, prints, and sculpture. Four gallery spaces are dedicated to the exhibition, which comprises more than 250 works.

Alibis: Sigmar Polke 1963–2010 brings together the work of Sigmar Polke (German, 1941–2010), one of the most voraciously experimental artists of the 20th century. This retrospective is the first to encompass the unusually broad range of mediums Polke worked in during his five-decade career, including painting, photography, film, sculpture, drawings, prints, television, performance, and stained glass. Polke eluded easy categorization by masquerading as many different artists—making cunning figurative paintings at one moment and abstract photographs the next. Highly attuned to the distinctions between appearance and reality, Polke elided conventional distinctions between high and low culture, figuration and abstraction, and the heroic and the banal in works ranging in size from intimate notebooks to monumental paintings. Four gallery spaces on MoMA’s second floor are dedicated to the exhibition, which comprises over 250 works and constitutes one of the largest exhibitions ever organized at the Museum. Alibis: Sigmar Polke 1963–2010 is organized by MoMA with Tate Modern, London. It is organized by Kathy Halbreich, Associate Director, MoMA; with Mark Godfrey, Curator of International Art, Tate Modern; and Lanka Tattersall, Curatorial Assistant, Department of Painting and Sculpture, MoMA. The exhibition travels to Tate Modern from October 1, 2014, to February 8, 2015, followed by the Museum Ludwig in Cologne, in spring 2015.

Beneath Polke’s irreverent wit and promiscuous intelligence lay a deep skepticism of all

authority—artistic, familial, and governmental. To understand this attitude, and the creativity that

grew out of it, Polke’s biography and its setting in 20th-century European history is relevant: in

1945, near the end of World War II, his family fled Silesia (in present-day Poland) for what would

soon be Soviet-occupied East Germany, from whic

h they escaped to West Germany in 1953. Polke

grew up at a time when many Germans deflected bl

ame for the atrocities of the Nazi period with

the alibi, “I didn’t see anything.”

Alibis is organized chronologically and across mediums, but begins in MoMA's Donald B.

and Catherine C. Marron Atrium with a sampling of works from across Polke’s career. The works

presented in this gallery reflect Polke’s persistent questioning of how we see and what we know,

and his constant experimentation with representational techniques, from the hand-painted dots of

Police Pig

(1986) to the monumental digital print

The Hunt for the Taliban and Al Qaeda

(2002),

which he described as a “machine painting.” Polke’s fluid approach to images and materials and

his embrace of chance as a way of undermining fixed meanings is exemplified in the selection of

films in the Marron Atrium, all of which have never before been shown publicly. The artist avoided

conventional narrative structures and often double-exposed the film material, superimposing

different layers of images. A preference for flux and a distrust of inherited categories are also

evident in the way Polke questioned the distinction between high and low culture, as in

Season’s

Hottest Trend

(2003),

which mocks the art market’s reliance on rarity by making a painting out of

tacky, mass-produced textiles. Polke also toyed

with language, often using verbal and visual

humor to make a claim while simultaneously positing its opposite—as, for example, in the painting

Seeing Things as They Are

(1991), whose title is reproduced on the back of a semitransparent

textile so that, when standing in front of the work, one sees the words in reverse.

The exhibition continues in the Marron Atrium with some of Polke’s earliest works,

alongside notebooks and publications from throughout his career. Polke made most of the works

in this section in his twenties, while a student at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, an influential art

school where many of the major German artists of his generation studied. For this generation, the

bravado of Pop art, which went hand in hand with the spread of American culture, was both a

fascination and a target. By adopting an adamantly clumsy approach to figuration in his earliest

drawings and paintings, he offered a sharp critique of consumerist behavior and popular taste,

with its desire for both sleek new furnishings and kitsch decorative elements. As the juxtaposition

of images and contradictory approaches in his notebooks demonstrate, Polke remained a

contrarian throughout his life.

The first gallery within MoMA’s Contemporary

Galleries begins with Polke’s work in the

1960s, when he examined the desires and drab realities of postwar reconstruction by singling out

images of food, housing blocks, and symbols of the often unrequited longing for leisure. His

source images were frequently drawn from newspapers and magazines, where the topics of the

day occupied the same page as cartoons and advertisements. Polke was particularly interested in

the halftone reproductions (images made up of grids of tiny dots that the eye blends to form a

picture) that were common in cheaply printed mass media. From 1963 onward, Polke created a

series of paintings in which he painstakingly transcribed—albeit not always faithfully—the dots of

his halftone source. He often began by spraying

a layer of paint through a perforated metal sheet;

to these dots he added others by hand. By creating or amplifying distortions in his source images,

he undermined the photographs’ alleged fidelity to

reality and collapsed the distinction between 3

figuration and abstraction. Works on view include

Chocolate Painting

(1964),

Girlfriends

(1965/66), and

Japanese Dancers

(1966).

The exhibition continues with Polke’s work

from the late 1960s, when he repeatedly

treated himself as a test subject and manipulated the structures of science to question its

rationality. By taking on such varied guises as a palm tree, his own doppelgänger, and a telepathic

medium, he embodied his own fluctuating view of

reality. Against the backdrop of worldwide

political and cultural upheavals and the space race

between the USSR and the United States, Polke

made it clear that the aims of science, such as

precision, measurement, and objectivity, were not

necessarily utopian or progressive. For

Cardboardology

(1968–69) and

People Circle

(1968), he

used office materials such as cardboard, ballpo

int pen, and twine to reflect how, despite the

flimsiness of the science behind Nazi eugenics, a huge bureaucracy charged with the

extermination of millions of people had developed around it. The works in this gallery also

represent Polke’s caustic dialogue with art

from the past and present. In the drawing

Constructions around Leonardo da Vinci

(1969), Polke’s ambiguous respect for and skepticism

about the station of artists in society is exemplified by an ironic but fond alignment of himself with

the great Renaissance scientist and artist.

The Large Cloth

of Abuse

(1968), with its aggressive

insults hurled across the canvas in a style reminiscent of Jackson Pollock’s famous drip paintings,

is an assault on both the veneration of Abstract Expressionist painting and the subsequent

emergence in the 1960s of Conceptual art, which often used analytical language as a primary

medium.

When Polke studied at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf in the early 1960s, abstraction had

returned—after having been deemed degenerate du

ring the Third Reich—as the dominant style of

modern art. But Polke was skeptical of this purportedly pure, non-referential visual language. In

the painting

Modern Art

(1968), he cataloged an array of stereotypical non-figurative painterly

forms, from geometric shapes to expressionist sp

lashes; however, with its white border and hand-

painted title, this pastiche looks more like a cheap reproduction. In the early 20th century, the

Soviet Constructivists heralded the social and utopian purpose of abstract art. But Polke evokes a

contrary association with the black and white lines in

Constructivist

(1968); by mimicking the

form of a partial swastika, Polke suggests that the return to abstraction in West Germany was a

specious attempt to mask the reasons for its pr

evious abandonment. Other paintings, in turn,

conflate abstraction with the mundane realm of decoration and kitsch, as when he adopts the

patterned grid—a key modernist motif—of store-bought fabrics that serve as both support and

background for a series of ostensibly idyllic yet outlandish sunset scenes dominated by pairs of

herons in

Heron Painting I

(1968) and

Heron Painting II

(1968). Polke’s approach to abstraction

was one of interrogation, however, rather than absolute rejection.

The works in the following galleries were largely made in the 1970s, a time of great social,

political, and artistic unrest, as well as widespre

ad experimentation with countercultural lifestyles

and drugs such as hallucinogenic mushrooms. In

these films, photographs, prints, and paintings, Polke created layered, mutable visions of everyday life, including altered states of consciousness.

This dense constellation of works is intended to evoke the stimulation of all the senses that occurs

during a hallucination. In 1973 Polke moved from

Düsseldorf to a farm in nearby Willich, where

the comings and goings of friends often led to artistic collaborations. Polke’s constant companion

during this time was his Beaulieu movie camera. To the handful of these films he showed publicly

during his lifetime, Polke added soundtracks by musicians such as the enigmatic Captain

Beefheart (Don Van Vliet), whose innovative compositions blended psychedelia and blues. During

this decade, Polke also traveled widely in sear

ch of unfamiliar experiences. All the while, he

remained keenly responsive to the political climate in Germany, as in

Dr. Bonn

(1978), a painting

that responded to the controversial deaths in 1977 of imprisoned members of the Red Army

Faction, a leftist German terrorist group. Works on view in this section include the paintings

Mao

(1972) and

Menschkin

(1972), and the films

How Long We Are Hesst/Looser

(c. 1973–76) and

Quetta’s Hazy Blue Sky

(c. 1974–76).

In 1981, after returning from more than a ye

ar of travel, Polke entered a period of

explosive experimentation as he rethought how and

out of what to make paintings. He employed

a broad array of both arcane and ordinary materials ranging from toxic Schweinfurt green paint to

newspaper clippings capturing the anxious politics of the Cold War period. Polke achieved complex

results with minimal means. In the triptych

Negative Value

(1982),

he used a few materials—

including a common, non-artistic synthetic purp

le pigment—and burnished the surface of the

painting to create iridescent gold, purple, green

, and bronze colors that change depending upon

the viewer’s position in the gallery.

Paganini

(1981–83) combines the figure of the Italian virtuoso

musician, who was said to have been assisted by the devil, with a demonic jester juggling symbols

of nuclear extinction—an ever-present threat during

the Cold War. As one looks closer, dozens of

swastikas also emerge.

The Living Stink and the Dead Are Not Present

(1983) juxtaposes painted

rows of binders—with the clinical inscriptions “Heilung” (healing) and “Besserung” (reform or

recovery)—with a printed textile of Arcadian scene

s by Paul Gauguin. Polke’s use of this kitsch

fabric suggests an ironic view of his own love of the exotic, which was a subject of fascination

during his earlier travels through Oceania and Southeast Asia. Making his images visually unstable

and conceptually ambiguous was one of the ways he sought to thwart the possibility of a definite

interpretation.

The next gallery offers an intimate view of Polke’s experiments with materials and

processes. He explored a variety of pigments, chem

icals, and techniques, many of which he tested

in small abstract paintings known as

Farbproben

(color experiments). In the related film, liquid

spills and piles of pigment seem to be characters

animated by invisible forces as they explode,

mix, and run across the canvas. Polke appears only briefly, pretending to paint his large canvas

with a tiny brush. Three works in a vitrin

e use photography, xerography, drawing, and

printmaking to simultaneously degrade images and generate new, unforeseen ones. In

Purple

(1986), Polke painted silk with a dye laboriously extracted from snails, harking back to a time

when this pigment, known as Tyrian or imperi

al purple, was highly prized and could not be

synthesized industrially. The wrinkled and pale result is anything but majestic, belying the hard

work that went into making the dye. In contrast, in the subtle and delicate

Velocitas-Firmitudo

(1986), Polke transposes marginal decorative elements from Albrecht Dürer’s 1522 woodcut

The

Great Triumphal Cart

onto nuanced clouds of graphite dust and silver oxide, conjuring a granular,

multidimensional space, distinct from the clearly defined perspectival space of Renaissance

painting that Dürer intensely explored.

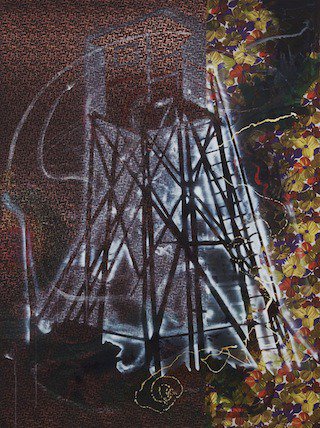

During a period of rapid and momentous developments—including the end of the Cold

War, the nuclear disaster in Chernobyl, the fall of the Berlin wall in 1989, and the reunification of

Germany—Polke worked with a broad view of histor

y in the works on view in the following gallery,

which are among his largest paintings. Between 1984 and 1988, Polke

created a group of

paintings in which a single watchtower is painted on surfaces ranging from bubble wrap to

collages of patterned textiles. The kind of tower in the image is commonly used for hunting in

Germany, but such structures also overlooked

the border between East and West Germany and

the perimeters of concentration camps during World War II. In these paintings, Polke used specific

images and materials to convey his ideas about the fugitive nature of vision and memory; for

example, in

Watchtower II

he covered the canvas with silver salts (light-sensitive compounds that

darken over time) so that the image, like a repressed memory, would ultimately disappear in a

black haze. Likewise, in four untitled works on glass from 1990, Polke obscured a once-

transparent surface with ornamental skeins of soot created with an ancient oil lamp.

Throughout the 1990s and the first decade of this century, Polke expanded his range of

tools and procedures for manipulating images. He often used chance events to create new

compositions by distorting his sources. In several works made using a copier, he moved the

source images while they were being scanned, yielding distorted forms that blur the distinctions

between abstraction and figuration, handmade an

d mechanical, and copy and original. In his

Printing Error

works, he similarly looked for irregularities

in the grids of tiny dots that compose the

halftone reproductions typically found in newspa

pers and magazines. He discovered meaning in

the way such “errors” fail to maintain the perfecti

on we expect from mechanical reproduction. The

culmination of these techniques can be seen in

the slide projections on view here, which bring

together drawing, photography, and xerox to suggest a rudimentary film. The so-called Lens

Paintings, such as

The Illusionist

(2007)

,

were another major interest for Polke in the 2000s. Their

surfaces are covered with an undulating, semitransparent layer that functions like a handmade

hologram, optically animating and deforming the pa

inting underneath as the viewer moves in front

of it.

The Illusionist

suggests that both magicians and artists deal in deception, making things

appear and disappear, recalling the origin of the word

alibi

—a Latin word meaning “in or at

another place.”

A major publication accompanies the exhibition, comprising 16 essays covering the entire span of Polke’s intermedial production, a comprehensive narrative chronology, an interview with Benjamin Buchloh on the groundbreaking 1976 solo exhibition of Polke’s work that he curated, an illustrated checklist, and a bibliography of publications from 1997 to the present. Texts are from a broad spectrum of artists and scholars, most of whom have not previously published work on Polke. The authors are Paul Chan, Christophe Cherix, Tacita Dean, Barbara Engelbach, Mark Godfrey, Stefan Gronert, Kathy Halbreich, Rachel Jans, John Kelsey, Erhard Klein, Jutta Koether, Christine Mehring, Matthias Muehling, Marcelle Polednik, Christian Rattemeyer, Kathrin Rottmann, Magnus Schaefer, and Lanka Tattersall.

The exhibition is made possible by a partnership with Volkswagen of America.

Major support is provided by Hanjin Shipping.

Image: Sigmar Polke. Watchtower (Hochsitz). 1984. Synthetic polymer paints and dry pigment on fabric, 9' 10" x 7' 4 1/2" (300 x 224.8 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Fractional and promised gift of Jo Carole and Ronald S. Lauder. © 2014 The Estate of Sigmar Polke/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Press Contacts:

Paul Jackson, (212) 708-9593 or paul_jackson@moma.org

Margaret Doyle, (212) 408-6400 or margaret_doyle@moma.org

Media preview Wednesday, April 9, 2014 10:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m.

Contemporary Galleries, second floor; The Donald B. and Catherine C. Marron Atrium, second floor; The Yoshiko and Akio Morita Media Gallery, second floor; Projects Gallery, second floor

The Museum of Modern Art MoMA

11 West 53 Street, New York, NY 10019

Hours:

Saturday through Thursday, 10:30 a.m.–5:30 p.m. Friday, 10:30 a.m.–8:00 p.m.

Museum Admission:

$25 adults; $18 seniors, 65 years and over with I.D.; $14 full-time students with current I.D. Free, members and children 16 and under.