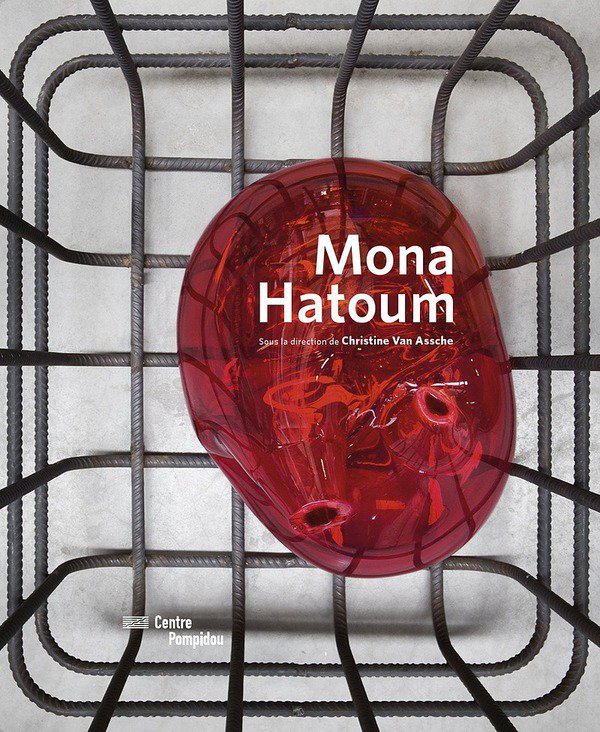

Mona Hatoum

dal 23/6/2015 al 27/9/2015

Segnalato da

23/6/2015

Mona Hatoum

Centre Pompidou, Paris

The exhibition provides audiences with a journey through her output based on formal and sensitive affinities between the works. In this way, the performances of the Eighties, whether documented in photos, drawings or videos, are seen in relation to installations, sculptures, drawings, photographs and objects dating.

Curated by: Christine Van Assche

In a world driven by contradictions, geopolitical tensions and diversified aesthetics, Mona Hatoum offers us an output that achieves unrivalled universality ? a body of work that has become a "model" for numerous contemporary artists. The Palestinian-born British artist is one of the key representatives of the international contemporary scene. Her work stands out for the relevance of its discourse, the perfect match between the forms and materials used, the multidisciplinary aspect of her work and her original, committed reinterpretation of contemporary art movements (performance, kineticism and minimalism).

After staging the first museum exhibition dedicated to Mona Hatoum's work twenty years ago, the Centre Pompidou is now devoting its first major monograph exhibition to her, featuring a hundred-odd pieces, and covering the multidisciplinary aspect of her work from 1977 to 2015. Without any chronological order, similar to a "map" of her career path, the exhibition provides audiences with a journey through her output based on formal and sensitive affinities between the works. In this way, the performances of the Eighties, whether documented in photos, drawings or videos, are seen in relation to installations, sculptures, drawings, photographs and objects dating from the late Eighties to the present day.

Mona Hatoum, born in the Lebanon in 1952 to parents of Palestinian origin, left that country in 1975 for a short stay in London just when war broke out in her homeland. She remained in the British capital, and began to study art. Her work falls into two main periods. During the 1980s, she explored the realm of performance and video. Her work at that time was narrative, and focused on social and political questions. From the 1990s onwards, her output has involved more "permanent" works ? installations, sculptures and drawings. Now situating herself as part of the avant-garde, Mona Hatoum explores installations influenced by kineticism and phenomenological theories, and other installations that can be defined as post-minimalist, using materials found in the industrial world (grids and barbed wire), or in her own environment (hair). Some of these installations and sculptures, most of which have a political dimension, are imbued with feminism. Around her gravitate somewhat Surrealist objects, works on paper produced with unusual everyday materials or photographs taken during trips, which have a link with other works in the exhibition. We talk to the artist.

Christine van Assche - You spent 23 years in the Lebanon, where you were born, and you have lived for 40 years between Britain and Berlin. How do you situate yourself between these different cultures, between the Middle East and the West ? or rather, how do you situate your work?

Mona Hatoum - I don't think one should see my work in these terms. I find it a pity that people approach my work with the idea of linking it with my origins. This limits their interpretation, and avoids the formal subtleties and comprehensive experience my works can offer. My work uses geometry, abstraction and the formal language of art. The large installations I have created since the early 1990s make reference to the architecture, the structures of power and control I have observed in the West. My roots lie in the Middle East. All my schooling took place in Beirut, a cosmopolitan city where I attended a French school, finished my studies in an Italian school and then went to an American university. So, long before leaving the Lebanon, I had already been exposed to a wide range of eclectic influences. This is a situation typical of the postcolonial situation in Arab and North African regions, where the conjunction of multiple cultural influences nourishes the psyche with its complexity and richness. I have already spent two-thirds of my life in England, and more recently I began to share my time between London and Berlin. I thus have a hybrid cultural experience, a plural existence, and I think that this is clearly reflected in the diversity of forms and approaches that appear in my work.

CVA - What do you mean when you refer to "the structures of Western power"?

MH - The constant surveillance imposed on society is one of the first things that struck me when I arrived in England. At the end of the 1970s, my commitment to feminist groups led me to examine the relations of power that existed ? firstly through the prism of the gulf between the genders, then through that of relations between the races. I also observed that the bureaucratic institution I was part of at the time (University College, London) was a microcosm of colonial powers. This observation pushed me to analyse the relationship between the West and the Third World. At the time, I was reading Foucault and Bataille, and was extremely interested in Panopticon and surveillance concepts, together with other mechanisms of state control.

CVA - All your work draws the spectator into a complex relationship, which is nonetheless different in the performances, sculptures and installation works. How are you developing this involvement?

MH - I like to draw people towards a visual and physical approach, so that associations or interpretations suddenly leap out from this first physical contact with the work. In my performances, I had a direct relationship with the audience, but when I began to create installations, I wanted the spectators' bodies to replace my own. Within very large installations, which can be quite imposing in terms of surface area, the spectator gradually becomes a part of the space and the formal elements of work, and eventually feels a sense of instability or danger, for example. With the sculptures ? especially when they take the form of domestic objects and furniture ? spectators can project their own bodies onto a work and imagine themselves in the process of using it. The fact that these works have been transformed into unusable and threatening objects pushes us to question the security of the world we live in.

CVA - How are the performances presented in the exhibition?

MH - A selection of performances ? 10 in all ? is presented, documented through photographs, sketchbooks and descriptive texts. Four video recordings of performances are also shown in the exhibition, representing the majority of the work I produced throughout the 1980s, together with the video pieces. Everything is spread out in the exhibition, thus providing a different perspective and experience of the visit, alongside more formal, experimental installations and sculptures.

CVA ? You have produced several videos that were not linked with performances. Do these correspond to a certain period in your career, or to certain specific explorations?

MH - In the 1980s, alongside my performances, which often included an element of live video, I produced several videos that were an extension of what I was doing at that time, based on temporality and narration. The first of these videos, So much I want to say, consisted of a performance with a slow scan satellite transmission, produced between Vancouver and Vienna in 1983. I also used sequences filmed in Super 8 during the performance Under siege (1982) to introduce chaos into the second part of the work Changing parts (1984). In addition, I totally reconfigured certain elements from an excerpt of a complex performance entitled Mind the Gap (1986) to create the video entitled Measures of Distance in 1988. Since then, I have produced installation/videos that deal with the problem of surveillance, such as Corps ?tranger (Foreign body) [a work produced in 1994 for the Centre Pompidou, which entered its collection the same year ? Ed.], together with a series of installations for which I projected sounds and live images captured in the street into the exhibition area, using a surveillance camera.

CVA - The exhibition features a number of impressive installations, which are minimalist in terms of materials and their relationship with space and the spectator. What do these installations represent in your work as a whole? How do you situate them in the minimalist movement?

MH - In the large installations, I used grids, the geometry of the cube, seriality and repetition, like formal minimalist systems. But when the cube turned into a cage and the grid became a barrier, they stopped being abstract: they made reference to confinement, control and in the end, the architecture of the prison. Some of these installations, like Light Sentence (1992), are performative and use light, shadows and movement to destabilise the space. Others, such as Map (clear) (2015) incorporate an unstable material ? here glass marbles ? in order to transform the ground beneath our feet into a deceptive surface. This work is thus only minimalist on a formal and aesthetic level. It is not self-referential, but open to interpretation and often makes reference to the instability and conflict present in the world we live in.

CVA - You also produce objects that seem to be based even more on Surrealism, and which have a distinct touch of humour. Is this deliberate on your part?

MH - Humour has always played an important role in my work. I have often associated it with a touch of Surrealism in order to contradict or deflate certain serious themes evoked in my first works. As with Roadworks, a 1985 performance where I walked barefoot through the streets of Brixton dragging heavy police boots behind me, or in the picture entitled Over my dead body, where the symbol of masculinity was reduced to a toy in the form of a little soldier. Humour is also evident in the sculptures such as Jardin Public (1993), Untitled (wheelchair) (1998-99), and T42 (gold) (1999). It can also be found in a series of sculptures where I enlarged inoffensive kitchen utensils to Surrealist proportions, and transformed them into threatening screens or beds. I am interested by Surrealism, because I see it as a visualisation of the contradictions and complexities that inhabit us, and a way of making art based on intimate reality rather than our logical spirit. The concept of the uncanny, or of the familiar thing that becomes disturbing ? or even menacing ? because it is associated with a certain trauma, has often featured in all my work in one way or another.

CVA - Which contemporary artists do you feel closest to?

MH - The artists who have inspired me at different stages of my career are Marcel Duchamp, Ren? Magritte, Meret Oppenheim, Agn?s Martin, Eva Hesse and Felix Gonzales-Torres ? though there are many others.

Press contact:

Benoît Parayre tel +33 (0)1 44781287 mail benoit.parayre@centrepompidou.fr

Céline Janvier tel +33 (0)1 44784987 email celine.janvier@centrepompidou.fr

Opening: 24 June 2015

The Centre Pompidou

Place Georges Pompidou 01 , Paris

open every day, except Tuesdays and 1 May,

from 11.00 a.m. to 10.00 p.m.