Robert Morris

dal 21/6/2005 al 30/7/2005

Segnalato da

21/6/2005

Robert Morris

Spruth Magers Lee, London

Early Sculpture

American born artist Robert Morris is widely considered to be one of the main exponents and practitioners of 1960’s Minimalism. Sprueth Magers Lee is pleased to be able to bring together several of the artist’s key early works, highlighting an important period in Minimalist art history.

In 1960 Morris and his wife, choreographer and dancer Simone Forti, moved to New York and quickly became involved with the Judson Dance Theatre. Morris’ change in practice from Abstract Expressionist painting into the fields of both sculpture and dance had been directly influenced by his work as a choreographer and prop maker within the varied group of artists and performers that made up the theatre. The sculptural work Columns (1961) is the first example of this shift and is also the earliest work in the exhibition. First appearing on stage as a surrogate dancer, the Column would move through what Morris termed to be performative and expressive positions. In the early sixties Morris would have several exhibitions in New York showing compositions of these stark architectural forms. The simple wooden construction of these pieces soon gave way to more industrially manufactured materials and processes, still maintaining Morris’ exacting and formal considerations in their aesthetic. Morris, like many other artists of the time sought to remove the imprint of technique or metier from the artwork, instead choosing to produce work that in no way bore the marks of its creator. The desired exchange between audience and artwork became pure aesthetic appreciation of form and for Morris this would become a removal of the artist himself.

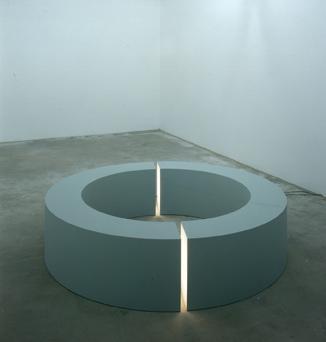

Morris’ later work Ring with Light (1965-66), was to become one of the main protagonists in Michael Fried’s attack on Minimalism in his essay ‘Art and Objecthood’ (1967). Written one month after the closing of the Los Angeles County Museum of Arts exhibition American Sculpture of the Sixties, Fried’s essay marked Morris’ work as a direct example of Minimalism’s ‘Theatricality’ in its direct involvement in the viewers experience of the artwork. Fried pinpointed Minimalism’s primary flaw as a reliance on its audience, discounting any artwork that required the existence or presence of any extraneous factor in its comprehension and visual understanding. In Fried’s eyes, the viewer’s durational participation with the works had become necessary for their completion and such deliberate attention to the context and placement of the sculptures rendered the works lacking and staged. Clement Greenberg’s earlier essay ‘After Abstract Expressionism’ (1962) laid the foundations for what he believed to be the correct pathway of Modernism’s continued progression; to follow a greater and more refined movement towards the entirely self-sufficient and autonomous art object. These texts had constructed a restrictive framework within which Minimalism could not function. Alongside contemporaries such as Donald Judd and Carl Andre, Morris would actively discount these increasingly redundant theories in favour of a criticality that held the experience of the audience as central to the artwork.

Like Judd, Morris was a prolific and engaged critical writer, publishing a manifesto for his own practice in ArtForum in 1968 in the essay ‘Anti Form’. This essay would cite his influence as an artist, reinforcing his appreciation of Romanian sculptor Constantin Brancusi. Brancusi’s obsession with the importance of the art work and its placement within its surroundings had encouraged much of Morris’ early work to deal specifically with the relationship between objects and the extent to which an artworks physical presence could affect its audience. Morris included Jackson Pollock’s action painting as a point of influence, marking his interest and movement towards his own experimentation with Process Art in the late sixties.

Morris would use many different media in his later practice, ranging from the ephemeral dirt pieces to the blindfolded drawings and films of the Seventies; each of which rejecting the forced or lasting manipulation championed by his early Minimalist works. Morris’ career has spanned over fifty years, throughout which the same interest in formally driven physical interventions have worked through a commitment to audience and context.

Morris’ work is included in many important collections across Europe and the US, including the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, the Hamburger Kunsthalle, in Germany and as a part of Tate Modern’s permanent publicly displayed collection here in London.

Spruth Magers Lee

12 Berkeley Street London W1J 8DT