Three exhibitions

dal 27/10/2006 al 27/1/2007

Segnalato da

De Pont museum of contemporary art

27/10/2006

Three exhibitions

De Pont Museum, Tilburg

Willem de Kooning / Jan Andriesse / Charlotte Dumas

Willem de Kooning

Paintings & sculptures from Dutch museums

October 28 through January 28, 2007

Two former directors of Dutch museums died last year. Edy de Wilde, born in 1919, headed the Stedelijk Museum from 1963 to 1985 and Rudi Oxenaar, born in 1925, the Kroller-Muller Museum from 1963 to 1990. The exhibition Willem de Kooning, paintings and sculptures from Dutch public collections and the presentation Picture books from the collection of Rudi Oxenaar are a tribute to these men who were so important for modern art and who both, as board members, have been closely involved in the establishment and development of De Pont museum of contemporary art.

On July 18, 1926 Willem de Kooning (1904-1997) managed to board, as a stowaway, a British cargo ship headed for America with the help of an acquaintance named Leo Cohan. It was certainly not an ambition to become one of the most prominent painters of the twentieth century that drove him to do this. Actually, he had not expected to find artists at all in America; at that time, he said in a 1960 interview, painters did not even comply with his notion of modern man. To him, America was a place where one could get ahead by working hard. And he wanted to achieve that as a commercial artist, having been trained in Rotterdam at the Gidding brothers' studio for interior decoration. How, at the end of a long and often difficult road, De Kooning became, during the 1950s, a major figure in the heroic generation of painters that gave American art an identity of its own for the first time is wonderfully described by Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan in his biography (2004).

In the Netherlands that success was hardly noticed at first. On a trip to New York in 1949, then director of Amsterdam's Stedelijk Museum Willem Sandberg ignored the advice of his American colleagues and forwent the opportunity to visit De Kooning. When A.M. Hammacher, director of the Kroller-Muller Museum, did see him one year later, he was indeed quite impressed but unable to exhibit the work of De Kooning in the Netherlands. The painter had his Dutch debut in 1956 at the Gemeentemuseum Den Haag, where Rudi Oxenaar was then curator. In the exhibition 50 years of art in the USA, De Kooning was represented with three paintings. These drew little attention however. The first real acquaintance with the work of Willem de Kooning took place in 1968 with his major retrospective at the Stedelijk Museum. On this occasion the artist, by this time sixty-four years old, set foot on Dutch soil again for the first time and received, at the opening, the International Talens Prize from jury chairman Rudi Oxenaar.

De Wilde's interest in the work of De Kooning dates back to the time when he was still director of the Van Abbemuseum. In 1959 he wrote his first letter to him, but it remained unanswered. In 1963 contact did come about while De Wilde was staying in New York; then he had just become director of the Stedelijk Museum. During that visit he must have seen De Kooning's recent work Rosy-Fingered Dawn at Louse Point. The museum purchased this in 1964: the first painting of his to be acquired by a European museum and, to this day, one of his most beautiful works.

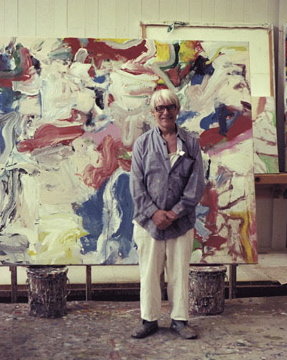

Until 1987, when De Kooning became increasingly affected by Alzheimer's disease, De Wilde visited him at least once a year at his impressive, self-designed studio in Springs, on the outermost point of Long Island. Personal dealings with artists were of great importance to De Wilde; this is how he gained a sense of the work's 'intensity', which was among the main criteria for quality in his view.

Intensity is a key word with the art of De Kooning. In order to translate sensory and emotional experiences into paintings that were a cross between abstraction and figuration, De Kooning took an intuitive approach, without clearly envisaging the end result. The strength of his paintings lies with the chemistry between the artist and the work in progress. During his visits, De Wilde also witnessed De Kooning's characteristic way of working. The act of painting was rapid and brief; this was continually interrupted by longer periods of concentrated observation meant to elicit the next step, as it were, from the painting itself.

'Willem de Kooning is unmistakably an American artist in terms of the vitality, the energy and the breadth of his approach (...) Yet his sensibilities and intellectual uncertainty, which are so characteristic of him, seem to have European origins,' De Wilde wrote in 1983 for the exhibition catalogue of North Atlantic Light, a retrospective comprised of paintings from the period 1960-1983. While his themes - the woman, the landscape and a fusion of the two - had remained basically unchanged throughout the years on Long Island, De Kooning continued to seek new painterly solutions.

In other respects as well, he was receptive to new ideas. While spending time in Rome in 1969, he modelled his first figures in clay, sculptures no larger than a hand. In the years to follow, he kept his concern for this. Both irregular and schematic, these seem to be three-dimensional versions of the 'blind' drawings that De Kooning produced while watching television in the evening.

Thirteen of the sculptures cast in bronze were donated to the Stedelijk by the artist. Together with the eight paintings, several drawings and prints, this became a unique collection of his late work. The only other work in a Dutch public collection, The Cliff of the Palisade with Hudson River, can be found at Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen. Like Rosy-Fingered Dawn, this gouache from 1963 is among De Kooning's abstract portrayals of landscape. The work is dedicated to Leo Cohan, who had provided De Kooning with a hiding place in the engine room of the SS Shelley in 1926. In 1977 Cohan donated this work, in his name as well as that of Willem de Kooning, to the museum in Rotterdam, the city from which De Kooning had departed roughly fifty years before.

The works in this exhibition have been generously lent by the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam and Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam.

Picture Books from the collection of Rudi Oxenaar

October 28, 2006 through January 28, 2007

Children's books and picture books, frequently found on travels abroad, have always had a special place in the Oxenaar family. Initially they were collected by Thil Oxenaar-van der Haagen. After her death Rudi Oxenaar continued, from the mid eighties onward, to develop his wife's collection. With this he confined himself to picture books produced since World War II, books which focus on the image and where text serves as no more than a further specification of that.

Just as with his collecting activities as director of the Kroller-Muller Museum, Oxenaar approached the task with expertise and single-mindedness. From the very start, his collection was international in scope. Picture books from the United States, where prestigious prizes such as the Caldecott Medal contribute greatly to the concern for the picture book, constitute an important part of his collection. But Japan, where Oxenaar has been several times and which, in his view, plays an equally pioneering role in this field, is also strongly represented. Completeness was never Oxenaar's aim. Quality was a decisive factor to him. He remained true to that principle when an illustrator admired by him had produced a less successful book or when his grown children brought him children's books from other countries.

The strict criteria employed by Oxenaar related to the imagination and originality of the illustrator, the artistic quality of the image, the surprising nature of the technique applied, the subtlety of the humor, fantasy and intensity with which the story is portrayed - in short, to all those facets that can make picture books unforgettable.

Rudi Oxenaar selected his picture books one by one and recorded his findings in small notebooks. Over a period of more than twenty years, he brought together seven thousand picture books from all over the world. From that immense wealth of material, graphic designer Tessa van der Waals has made a selection of roughly one hundred picture books, which give an impression of the diversity present in this highly personal collection.

Picture books only begin to come alive when they can be held in one's own hands. For that reason, this presentation also makes a large number of picture books available for perusal.

************

Jan Andriesse

30 years of drawing

September 23 through January 7, 2007

Artist and researcher: Jan Andriesse (Jakarta 1950) takes many approaches to the phenomenon of light. As one of the makers of the documentary Hollands Licht (2003) he set out to discover the characteristic properties of light; as an artist he attempts to express its miraculousness in images.

De Pont has followed the work of Jan Andriesse for years and has a number of drawings and paintings by him in its collection. The exhibition that the museum is now dedicating to his work provides a retrospective view of drawings produced since 1978. The emphasis lies not so much with completeness as with diversity. In the early drawings figuration is juxtaposed with abstraction. In the later work small drawings are alternated with several larger 'drawn' paintings, a drawing done directly on the wall and a maquette of this exhibition. But the most striking aspect of Andriesse's drawings is that direct observations from nature and carefully constructed, geometric drawings coexist in the work as two expressions of the same fascination.

No matter how he approaches his subject - light, space and water - observation remains the prime concern. Jan Andriesse never gets tired of the view from his houseboat studio: the Amstel River, always the same but constantly changing according to the weather conditions, the time of day and the time of year. In a series of studies on water, from 1998, Andriesse has captured the agile play of reflective light. Sometimes a single detail evokes the actual situation: the hull of a boat that casts a heavy shadow, the reflection of the moon that becomes multiplied on the rippling water, or a coot that swims by and leaves a V in its wake. But usually the drawings consist of graphic patterns of light and dark which, despite their diversity, are always recognizable as depictions of water. Aside from the observations of nature, there are the meticulously constructed drawings of curves and lines that intersect, meet and divide each other. These works are closely related to the paintings in which Andriesse evokes, with minimal means, the current of the river, the profile of a bridge or the dividing line between land, water and sky. While the curved lines and forms do not reveal their origins in the paintings, the drawings show the geometric construction on which the composition is based. Rather than being preliminary studies, these are drawings made in retrospect, as a kind of justification for the developmental process that took place in the painting. In that process the ratio of the golden section plays an important role. Just as the Renaissance painters made use of geometry for the construction of a central perspective, so are Andriesse's compositions based on a framework of triangles, rectangles, pentagons and curves in which the ratio 1:0.618 of the golden section continues to recur. This is how he anchors the bend of a spiral, the position of the curved lines or the point at which these meet. The laws of geometry provide stability to the 'panta rhei', or pervasive flux, of light and water. And at the same time the golden section, the Fibonacci numbers and the seven basic forms of the curve furnish Andriesse with the autonomous and universal set of instruments by which he can give shape to his sensory emotion without lapsing into the overly personal or to the banality of the cliche'.

Andriesse 'discovered' the golden section during the early eighties, when he was grappling with the issue of what course to take, having rejected both abstraction and figuration as being too limited. A 1979 drawing involving a square and a long, tilted rectangle still shows this abstraction. The geometric forms relate to each other not only in terms of position and color, but also in size. Though the square and the beam differ in appearance, their surface is identical. The title of this work, the same and the other, has been borrowed from the Greek philosopher and mathematician Pythagoras, who allegedly gave this as an answer on being asked about his image of God. The intangible nature of Pythagoras's all-embracing characterization is conveyed in the work of Andriesse. Despite, or perhaps in fact because of the concreteness of his mathematical constructions, the analogies with nature are maintained; in the form of the ellipse, in the catenary as an embodiment of gravity and in the principle of natural growth, which forms the basis of the number sequence of Fibonacci.

Echoes and analogies can also be heard among the works themselves. In the organic shapes of the series studies for Caryatide (1994) the curved lines of undulating water recur in a different form, as upright and materialized hybrid shapes: the same and the other.

Among the carefully constructed drawings, there is one that stands out. On a large drawing from 2004, a brownish cloud-like shape is interrupted on the right by an austere, white rectangle. The transition from dark to light and the blending of organic and geometric forms has not been created deliberately but has come about by chance, due to the effect of moisture on a blank sheet of paper; when this happened, the rectangular area was covered in such a way that the moisture could not affect the paper there. All that Andriesse himself added to this work is the text: alle richtingen - andere richtingen (all directions - other directions).

The text refers to a traffic sign that he encountered years before, while driving through Belgium, at a T-junction: alle richtingen appeared on the sign pointing left, while the one pointing to the right read andere richtingen. In the paper damaged by a leak at his studio, Andriesse finally found the visual equivalent for this paradox; the same and the other.

The exhibition will be accompanied by a special publication, dedicated to the subject Kitsch.

Contributions have been made by roughly forty authors who, at Jan Andriesse's request, conveyed their thoughts on the phenomenon.

************

Charlotte Dumas

project-space

November18, 2006 through January 21, 2007

The exhibition Reverie consists of two recent series of photographs by Charlotte Dumas (Vlaardingen 1977). In the series of 'portraits' made in the stables of racetracks in Paris and Palermo during the early part of 2006, Dumas focused on the horse, an animal that appeared in her work at an earlier stage as well. For the other series being shown, she travelled to reserves in Norway, Italy, Germany and the United States over the past year. In these photographic portraits, she has portrayed the wolf.

Animals are a well-liked subject in our visual culture, but in the context of visual art they are hardly considered a serious theme. In defiance of this supposed triviality, Charlotte Dumas has made police dogs, horses and now wolves the subject of her photography since graduating from the Rietveld Academie in 2000.

Not a trace of irony or sentimentality can be found in her work. Characteristic of her approach is the unbiased concern with which she portrays her subject. The sizes of the photographs are substantial, yet not so large that intimacy is lost. The animals are placed centrally and monumentally on the image surface, in poses that precede or follow the action. We see a full focus on their stance, on the softness and the nuances of color in their coats or the relief of veins on glistening skin. These are quiet images, which seem to elude the momentary quality of the 'here and now' due to their setting and incidence light.

Dumas takes her inspiration more from painting than from photography. Delacroix and Ge'ricault are the shining examples for her. She is fascinated by the way in which these artists have portrayed horses - heroically and tragically, as passionate and dedicated creatures. Like these painters, Dumas is primarily interested in the eloquence of the image. In addition to the cropping and the pose, she employs light as a means of achieving this in her photographs.

With the 2004 series Day is done she showed the horses of Rome's mounted police in all their vulnerability, in the nocturnal darkness of the stables. The series now on view remains closer to the traditional horse portrait. But due to the recurrent motif of the ropes and chains that restrain the animals, as well as the halters and brightly colored covers under which the horses are sometimes almost entirely concealed, the photographs acquire connotations that differ greatly from those in traditional photographs of horses. And then there is the incidence of light that gives the images a poetry of their own. In the portraits photographed in Paris the light has rich contrast, intensity and expressiveness, while those made in Palermo have a clarity of light, which lends a certain serenity not only to the horses but also to the weathered wall behind them.

With her portraits of wolves, Dumas has taken an entirely different approach. While the series involving horses derives its strength and rhythm from the consistent manner in which they have been photographed, the wolf is always portrayed in a different way: looking up, sleeping, hunting, watchful or relaxed. But here, too, the incidence of light is essential to the sometimes almost brittle atmosphere.

Just as with the horse, the thematic appeal that the wolf has for Charlotte Dumas relates to man's complex relationship with this animal. The symbolic and emotional connotations that both the horse and the wolf have in our culture make up the context within which her portraits reveal themselves. Whereas the horse, as man's trusty companion in war and peace, symbolizes the close bond between man and nature, the wolf represents the other end of the spectrum. The often vehement reactions evoked by this 'underdog' among the predators vary from nearly moral loathing to a 'grizzly-man' desire for identification. The images created by Dumas escape any such unambiguous characterization. That clearly emerges in the confrontation of the two series. Despite the traits ascribed to wolves, they assume a certain vulnerability when juxtaposed with the scarcely controllable temperament of the horses. A trace of melancholy can be found in both series.

De Pont museum of contemporary art

Wilhelminapark 1 - Tilburg

Open Tuesday through Sunday 11 am - 5 pm, Closed Monday, Open on public holidays, except for December 25 and January 1

Admission: Adults € 6,00, Groups of at least 15 people € 4,00, Students, 65+ € 3,00