Thomas Baumhekel

dal 14/2/2007 al 12/5/2007

Segnalato da

14/2/2007

Thomas Baumhekel

Museum fur Angewandte Kunst, Frankfurt

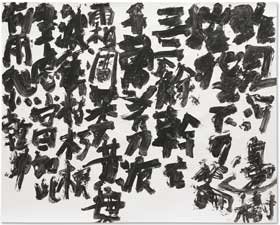

Sign language. The artist fell victim to the fascination of Chinese characters because of their structure and so initially approached their content through their form.

Sign language

Thomas Baumhekel, who lives and works in Dresden, has been fascinated by writing Chinese characters for more than fifteen years, whereby his engagement with China and its writing system is of a purely intellectual kind; the furthest he has ever travelled eastwards was a visit to the city of Leningrad many years ago. In his student years, writing systems were already the focus of Baumhekel's artistic work – the Cyrillic alphabet as well as Neolithic cave drawings and sign systems he developed himself; consciously or unconsciously, the gestural cipher art of A.R. Penck, who was born in Dresden in 1939, may have been a source of inspiration. Baumhekel fell victim to the fascination of Chinese characters because of their structure and so initially approached their content through their form. Yet this does not mean that the texts, usually Taoist or Buddhist, which he puts down on paper are not deliberately chosen.

Free of the burden of tradition with which, as a rule, a script artist in the Far East grows up, Baumhekel allows himself an uninhibited approach, and it is this that largely constitutes the charm of his works. He does not use the typical eastern Asian absorbent paper, preferring to write mainly on large sheets of white drawing paper. For his more recent works he used an ink mixture which does not quite blend, but instead gives the lines an internal structure which makes the sequence of the lines and the writing process understandable even for the lay person. As a result, the time factor can be visually experienced. These structures also conjure up associations with the grain of wood. Sometimes the lines seem like boards nailed together and thus form a link to those works for which he used driftwood or other wooden finds as a ground. The writing works thus take on a new form of physicality or develop inthe direction of the sculptural. For all their expressive force, Baumhekel's signs have nothing elegant, pliant or yielding about them. Here a certain affinity to the exotic enters into a special bond with unaffected naturalness.

The focal point of the exhibition in Frankfurt is the installation Treibholz (Driftwood) which consists of found pieces of wood – Baumhekel's studio in Dresden-Pratzschwitz is not far from the river Elbe. By writing short Chinese texts on these he gives the weathered pieces of wood a new level of meaning, which of course is also mysterious for anyone unable to read it. Over a length of almost 30 metres, a “river” runs through the museum's China Gallery, its rhythmic structures provided by the driftwood and the texts on them. In the Taoist sense, this work stands for the principle of constant change, the basis of our very existence. This message is also underscored by the time factor imminent in the work – the installation entails works from the years 1997 to 2006, thus spanning a time-continuum of ten years.

This installation is being shown together with various works on paper, of which the cycle of poems by the Chinese Zen Master Han Shan takes up the most space. This particular figure is more the focus of legend than of historical fact. He is said to have left the “world of dust”, presumably in the mid-7th century, to retire to a summit of the Tiantai Mountains, called Cold Mountain (Han Shan). Soon, the name of the mountain became intermingled with that of the poet himself and his search for the ultimate truth. Despite philological efforts, it is still a matter of speculation whether a single historical personality is behind the preserved texts. Han Shan, often seen together with the foundling Shi De and the Zen Master Feng Gan, turns up in countless works of East Asian painting, in the form of a totally wild figure with ragged clothes and unruly hair, depicted wandering through the mountains, drawing on cliff faces, engrossed in blank scrolls or discussing the teachings of Buddha and Tao with his two comrades. Han Shan became the prototype of the successful Zen lay-person who arrives at true insight without monastic rules, in cheerful serenity.

Museum fur Angewandte Kunst

Schaumainkai (Museumsufer) 17 Frankfurt am Main

Opening hours: Wed 10 - 21; Tue and Thru - Sun 10 - 17.