Divisionism / Neo-Impressionism

dal 25/4/2007 al 5/8/2007

Segnalato da

Vittore Grubicy De Dragon

Emilio Longoni

Angelo Morbelli

Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo

Gaetano Previati

Giovanni Segantini

Georges Seurat

Paul Signac

Camille Pissarro

Giovanna Ginex

Vivien Greene

Dominique Lobstein

Aurora Scotti Tosini

Ellen Lee

25/4/2007

Divisionism / Neo-Impressionism

Guggenheim Museum, New York

Arcadia and Anarchy. First U.S. exhibition to focus on Italian Divisionism and its relationship to French Neo-Impressionism. The exhibition comprises 40 paintings drawn from major museums and private collections including Giovanni Segantini, Angelo Morbelli, and Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo, together with significant oevre by Georges Seurat, Paul Signac, and Camille Pissarro, among others.

Arcadia and Anarchy

First U.S. Exhibition to Focus on Italian Divisionism and Its Relationship to French Neo-Impressionism

From April 27 to August 6, 2007, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum presents Divisionism/Neo-Impressionism: Arcadia and Anarchy, the first exhibition in the United States to focus on Italian Divisionism —a style so named for its painting technique, which employed the “division” of vibrant color through brushstrokes— and to examine its relationship to French Neo-Impressionism. The exhibition comprises approximately forty paintings drawn from major museums and private collections by the masters of Italian Divisionism, including Giovanni Segantini, Angelo Morbelli, and Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo, together with significant Neo-Impressionist paintings by Georges Seurat, Paul Signac, and Camille Pissarro, among others. Divisionism/Neo-Impressionism situates the Italian Divisionists within an international context alongside the major proponents of Neo-Impressionism.

Divisionism emerged in Northern Italy around the end of the 1880s. The first generation included Vittore Grubicy De Dragon, Emilio Longoni, Morbelli, Pellizza, Gaetano Previati, and Segantini. Their painting method was characterized by the juxtaposition of strokes of pigment to create the visual effect of intense single colors. While these artists were anchored in the traditions of Italy’s artistic heritage, they took cues from the modernist practices occurring elsewhere in Europe, primarily those of the French Neo-Impressionists, or Pointillists. They were also influenced by the optical and chromatic ideas developed by French and American scientists, namely, Michel-Eugène Chevreul and Ogden Rood.

The shared concerns of the Neo-Impressionists and Divisionists, paired with the latter’s emergence at a slightly later date, have often caused the Italian style to be regarded as a derivation of the French one. Yet distinct differences marked the Divisionists’ art, and the exhibition reveals that they developed an idiom that was all their own. This included a preference for large-scale compositions, an ongoing interest in modeled form and the representation of three-dimensional space, and a desire to connote movement. Unlike the French, Belgians, or Dutch, the Italians eschewed representations of bourgeois life or urban spectacle. Instead, they painted Symbolist imagery, largely absent from the work of their European contemporaries. Underlining the paradoxical nature of Italian art in this period, these pursuits both reflected the Divisionists’ grounding in Italy’s rich visual heritage and pointed the way for the next generation, the Futurists.

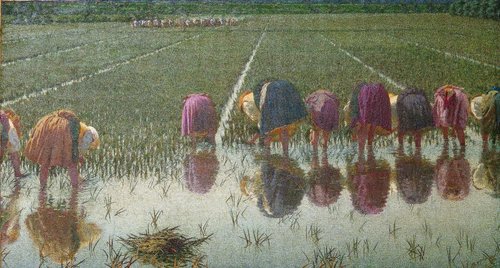

The exhibition is organized in five thematic groupings—“Light,” “Landscape,” “Rural Life,” “Social Problems,” and “Symbolism”—to address the concerns these artists shared as well as to reveal how their work diverged. The first section, “Light,” demonstrates the preoccupation with the depiction of refracted lamplight upon color in interiors. “Landscape” features works that capitalize on the effects of sunlight, particularly in the reflective surfaces of rivers, lakes, glaciers, and the sea. “Rural Life” denotes the pervasive representations of agrarian labor in aesthetically beautiful images that seemingly contradict the hardships implicit within these scenes. In contrast, the paintings in “Social Problems” more directly call attention to the political issues of the day by portraying strikes, industrial labor, and the urban malaise of the working class. Finally, “Symbolism” reveals the direction taken in the late 1890s, primarily by the Italian Divisionists, when artists turned away from political matters to realize transcendent allegorical or spiritual visions.

The exhibition’s subtitle, Arcadia and Anarchy, literally and metaphorically alludes to philosophies shared by many Divisionist and Neo-Impressionist artists. Their choice of a radical new style was as anarchic as their allegiance to leftist politics, but their search for the ideal led to arcadian evocations in idyllic landscapes and mystical imagery.

Catalogue

A fully illustrated catalogue with scholarly essays by Italian, French, and American authors, which expand the current discourse on the subject, accompanies the exhibition. The authors are Giovanna Ginex, Vivien Greene, Dominique Lobstein, and Aurora Scotti Tosini.

Public Programs

Unless otherwise noted, all public programs take place in the Peter B. Lewis Theater, Sackler Center for Arts Education.

A panel discussion, “Art for Humanity,” addressing the painting and politics of the Neo-Impressionists and the Italian Divisionists, is held at the museum on Monday, April 30. Speakers include Mark Antliff, Professor of Art History, Duke University; Giovanna Ginex, independent art historian, Milan; and Ellen Lee, The Wood-Pulliam Senior Curator, Indianapolis Museum of Art.

On Tuesday, July 10, 6:30 p.m, in a program entitled “In Paint and Film: Riso Amaro,” exhibition curator Vivien Greene speaks on Angelo Morbelli’s painting For Eighty Cents! (1895) and introduces Giuseppe De Santis’s film Riso Amaro (Bitter Rice, 1945, 107 minutes), both of which feature women working rice fields in Piedmont, Italy.

Every Tuesday morning in June (5, 12, 19, 26), beginning at 11:30 a.m., Italian films screen in the News Corporation New Media Theater. Selections include Francesca Bertini and Gustavo Serena’s Assunta Spina (1915, silent film with music track, 50 minutes), a precursor to 1940s Italian neorealism; and Luchino Viscounti’s Il Gattopardo (The Leopard, 1963, restored English language version, 161 minutes), an epic film that re-creates the tumultuous years when the aristocracy lost its grip on power and the middle class led the formation of a unified democratic Italy. Screenings are free with museum admission.

Generous support for this exhibition is provided by the Italian Cultural Institute of New York.

The Leadership Committee for Italian Art at the Guggenheim Museum is gratefully acknowledged.

Additional support is provided by an indemnity from the Federal Council on the Arts and the Humanities.

The museum thanks the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs for its patronage.

The exhibition was organized by Vivien Greene, Associate Curator, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, and premiered at the Deutsche Guggenheim in Berlin earlier this year.

Image: Angelo Morbelli, Per ottanta centesimi!, 1895. Oil on canvas, 69 x 124.5 cm. Museo Francesco Borgogna, Vercelli. Photo: Giacomo Gallarate

For additional information contact:

Betsy Ennis / Leily Soleimani Guggenheim Public Affairs 212 4233840 E-mail: publicaffairs@guggenheim.org

Preview: Thursday, April 26, 10 a.m.–Noon

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

1071 Fifth Avenue (at 89th Street), New York