Geometry of Motion 1920s/1970s

dal 18/3/2008 al 22/6/2008

Segnalato da

El Lissitzky

Laszlo Moholy-Nagy

Hans Richter

Marcel Duchamp

Robert Irwin

Gordon Matta-Clark

Robert Smithson

Anthony McCall

Klaus Biesenbach

Roxana Marcoci

18/3/2008

Geometry of Motion 1920s/1970s

The Museum of Modern Art - MoMA, New York

Taking cinematic experience as its point of departure, this exhibition uses 14 historic works to trace the transformation of the art object from static image to fluid light projection within two artistic lineages: the unconventional optical techniques of the 1920s Neue Optik, or "New Vision," generation of artists, among them El Lissitzky, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, Hans Richter, and Marcel Duchamp; and the situational aesthetics advanced by Robert Irwin, Gordon Matta-Clark, Robert Smithson, and Anthony McCall in the 1970s.

Exhibition organized by Klaus Biesenbach, Chief Curator, Department of Media, and Roxana Marcoci, Curator, Department of Photography

The Museum of Modern Art presents Geometry of Motion 1920s/1970s, on view in the second-floor Yoshiko and Akio Morita Media Gallery from March 19 through June 23, 2008. The phrase “geometry of motion” in the exhibition’s title derives from the literal meaning of the French word cinématique. Taking cinematic experience as its point of departure, this exhibition uses fourteen historic works to trace the transformation of the art object from static image to fluid light projection within two artistic lineages: the unconventional optical techniques of the 1920s Neue Optik, or “New Vision,” generation of artists, among them El Lissitzky, László Moholy-Nagy, Hans Richter, and Marcel Duchamp; and the situational aesthetics advanced by Robert Irwin, Gordon Matta-Clark, Robert Smithson, and Anthony McCall in the 1970s. All of these artists have explored new perceptual propositions for the geometry of motion, conveying indelible filmic even ts.

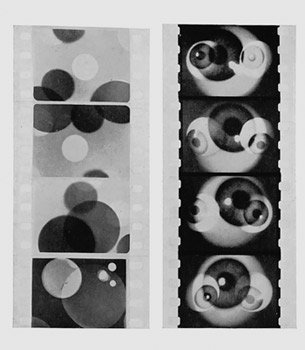

From 1919 to 1923, Lissitzky developed his Prouns, paintings and works on paper of translucent and opaque abstract planes, some of which were intended to be rotated or hung in any direction, and which evolved into fully three-dimensional installations. A few years later, Moholy-Nagy conceived Light Prop for an Electric Stage (Light-Space Modulator), a mobile light mechanism that materialized its creator’s goal of “painting with light” into space. Also in the 1920s, Richter translated geometrical shapes into pure cinematic sensation. His pioneering abstract films, exemplified in the exhibition by the four-minute film Filmstudie (1926), codified a visual syntax based on rhythmical patterns of light and motion. Richter’s interest in experimental cinema was related to Duchamp’s abstract optical tests with rotary discs and afterimages that in 1926 resulted in Anémic Cinema (also on view at MoMA), a film alternating shots of rotating spirals w ith discs inscribed with erotic puns.

During the 1970s, a new generation of artists built on the earlier artistic experiments with light to tap into sensory perception. This is the case with Matta-Clark’s anarchitectural projects that carved unexpected, vertiginous apertures of light into abandoned buildings, and with Irwin’s light installations that heightened spatial perception. Concurrently, Smithson explored the idea of experiencing art as itinerant and filmic in his monumental Spiral Jetty, orchestrated in 1970 at the Great Salt Lake in Utah. The exhibition includes Smithson’s film of the completed sculpture taken from a helicopter, capturing the moment when the sun’s reflection hit the water at the exact center of the spiral. Looking directly into the sun is not unlike turning away from the screen in a movie theater to look into the film projector’s beam. McCall draws upon this accidental occurrence, fusing the properties of film and sculpture in his slide projection Miniature in Black a nd White (1972), a precursor of his solid light films.

Geometry of Motion 1920s/1970s brings together historic light- and movement-capturing experiments that draw attention to the conditions and complexities of perception, both within the framework of institutional display and in outside surroundings. It also complements the survey exhibition Take your time: Olafur Eliasson (April 20 - June 30, at MoMA and P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center) by offering context to Eliasson’s protocinematic experiments with mechanisms of motion, projection, shadow, and reflection.

Image: Hans Richter. Still from Filmstudie. 1926. 35mm film transferred to video (black and white, silent). Film in the permanent collection of The Museum of Modern Art, New York

PUBLIC PROGRAM

Proto-Cinema: Contemporary Art and the Geometry of Motion

Tuesday, April 22, 6:30 p.m.

The Celeste Bartos Theater, 4 West 54th Street

From Andy Warhol’s conceptual use of filmmaking in Empire to Olafur Eliasson’s incorporation of cinematic effects in his environments and installations, the mechanics of the projected and perceived image have played a significant role in the art of recent decades. This program explores how contemporary artists address the interstice between film and photography by deconstructing these mediums. Participants include Kerry Brougher, Acting Director and Chief Curator, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C.; Chrissie Iles, Anne and Joel Ehrenkranz Curator, Whitney Museum of American Art; and Anthony McCall, artist. Moderated by Klaus Biesenbach and Roxana Marcoci.

Tickets can be purchased at the lobby information desk, the film desk, or online at http://www.moma.org/thinkmodern

For press inquiries, please contact Kim Donica at 212/708-9752 or kim_donica@moma.org

The Museum of Modern Art

11 West 53 Street New York, NY 10019