Art of Two Germanys

dal 24/1/2009 al 18/4/2009

Segnalato da

Willi Baumeister

Carlfriedrich Claus

Hans Grundig

Werner Heldt

Hannah Hoch

Ernst Wilhelm Nay

Wilhelm Rudolph

Richard Peter Sr.

Fritz Winter

Ursula Arnold

Rudolf Bergander

Chargesheimer

Arno Fischer

Hermann Glockner

Konrad Klapheck

Willi Sitte

ZERO group

Georg Baselitz

Joseph Beuys

Hartwig Ebersbach

Bernhard Heisig

Eva Hesse

Jorg Immendorff

Anselm Kiefer

Konrad Lueg

Markus Lupertz

Wolfgang Mattheuer

Blinky Palermo

Sigmar Polke

A. R. Penck

Gerhard Richter

Dieter Roth

Thomas Schutte

Werner Tubke

Autoperforationists

Klaus vom Bruch

Lutz Dammbeck

Todliche Doris

Harun Farocki

Isa Genzken

Hans Haacke

Georg Herold

Martin Kippenberger

Via Lewandowsky

Marcel Odenbach

Albert Oehlen

Helga Paris

Thomas Ruff

Katharina Sieverding

Thomas Struth

Rosemarie Trockel

24/1/2009

Art of Two Germanys

Los Angeles County Museum of Art - LACMA, Los Angeles

Cold War Cultures. For East and West Germany during the Cold War, the creation of art and its reception and theorization were closely linked to their respective political systems. Reacting against the legacy of Nazism, both Germanys revived pre-World War II national artistic traditions. Yet they developed distinctive versions of modern and postmodern art. By tracing the political, cultural, and theoretical discourses during the Cold War in the East and West German art worlds, Art of Two Germanys reveals the complex and richly varied roles that conventional art, new media, new art forms, popular culture, and contemporary art exhibitions played in the establishment of their art in the postwar era.

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) presents Art of Two

Germanys/Cold War Cultures (on view January 25 to April 19, 2009), the

first major exhibition in the United States to examine the range of art

created during the Cold War. Art of Two Germanys/Cold War Cultures

continues LACMA’s tradition of thematic explorations of twentieth century

German art in its political, social, and historical contexts and is cocurated

by LACMA’s Stephanie Barron and Eckhart Gillen of Kulturprojekte

Berlin GmbH. Barron previously curated two critically acclaimed German

exhibitions at LACMA—“Degenerate Art”: The Fate of the Avant-Garde in Nazi

Germany (1991) and Exiles and Emigrés: The Flight of European Artists from

Hitler (1997).

For East and West Germany during the Cold War, the creation of art and its

reception and theorization were closely linked to their respective

political systems: the Western liberal democracy of the Federal Republic

of Germany (FRG) and the Eastern communist dictatorship of the German

Democratic Republic (GDR). Reacting against the legacy of Nazism, both

Germanys revived pre-World War II national artistic traditions. Yet each

developed their own distinctive versions of modern and postmodern art—at

times in accord with their political cultures, at other times in

opposition to them. By tracing the political, cultural, and theoretical

discourses during the Cold War in the East and West German art worlds, Art

of Two Germanys reveals the complex and richly varied roles that

conventional art, new media, new art forms, popular culture, and

contemporary art exhibitions played in the establishment of their art in

the postwar era.

Barron explains, “Modern and postmodern German art has been generally

identified with expressionism, which has prevented a more complex reading

within an international context. This reception of German art has been

inextricably connected to national identity and political context. Art of

Two Germanys/Cold War Cultures is the first exhibition since the end of

the Cold War to fully examine the intricacies of the art of the two

Germanys without reducing the works to familiar binaries of East versus

West, national versus international, and traditional and static mediums

versus open and experimental art forms. The exhibition mines these

complexities, ultimately revealing a more multifaceted perspective on the

art of East and West Germany.”

Art of Two Germanys is the first special exhibition to go on view in

LACMA’s new Renzo Piano designed-building, the Broad Contemporary Art

Museum (BCAM). Divided into four chronological sections, the exhibition

includes approximately 300 paintings, sculptures, photographs, multiples,

videos, installations, and books by 120 artists. The show features large

scale installations and recreations of major works by Hans Haacke, Heinz

Mack, Sigmar Polke, Raffael Rheinsberg, Gerhard Richter, and Dieter Roth,

as well number of videos and performance-based works.

Section I: 1945–1949

Artists: Willi Baumeister, Carlfriedrich Claus, Hans Grundig, Werner

Heldt, Hannah Höch, Ernst Wilhelm Nay, Wilhelm Rudolph, Richard Peter Sr.,

Fritz Winter, and others

Art of Two Germanys/Cold War Cultures begins with the defeat of Germany at

the end of World War II. The work generated during this period illustrates

artistic ruptures and continuities in relation to the surrealist and

expressionist traditions before 1933. The depiction of war, ruins, and

mourning represented in works by Hans Grundig, Werner Heldt, Hannah Höch, and Richard Peter Sr. reveals artists dealing with the devastated

landscape and exploring the mindsets of the German people following the

war. The so-called formalism debate of 1948 in the West defined realism as

the appropriate form of representation for a new socialist society, and

the pluralism of stylistic expression in East Germany consequently

narrowed. Abstract and semi-abstract work by Willi Baumeister, Ernst

Wilhelm Nay, Fritz Winter, and others in the West was associated with

freedom and democracy, thus possessing its own definite political stance

as well.

Section II: The 1950s

Artists: Ursula Arnold, Rudolf Bergander, Chargesheimer, Arno Fischer,

Hermann Glöckner, Konrad Klapheck, Willi Sitte, ZERO group, and others

The contradiction of West Germany’s reliance upon now-flourishing

modernist abstraction and East Germany’s connection to Soviet-style

socialist realism is explored in the second section of the exhibition,

which encompasses the 1950s. During that economically robust period in the

West, abstraction and the dependence on new materials was evidenced by the

ZERO group (Heinz Mack, Otto Piene, and Günther Uecker), which, in works

like Mack’s elaborate installation Relief Wall from the Diogenes Gallery

(1960), examined relationships among science, technology, and art as well

as questions of perception. Simultaneously, a realistic pictorial language

emerged in the East in the works of painters such as Rudolf Bergander and

Heinrich Witz. Hermann Glöckner, whose previously unseen work is a feature

of the exhibition, was one of the few artists working privately in the East. He created a group of constructivist objects from found materials

and challenged the image of art produced in the GDR, since the aim was

neither to champion socialist principles nor to critique them. The

optimism of the so-called economic miracle in the West was questioned by

critically focused photographs by Chargesheimer working in the Rhineland;

in the East Ursula Arnold and Arno Fischer captured images of contemporary

society that were critical of official views.

Section III: The 1960s and 70s

Artists: Georg Baselitz, Joseph Beuys, Hartwig Ebersbach, Bernhard Heisig,

Eva Hesse, Jörg Immendorff, Anselm Kiefer, Konrad Lueg, Markus Lüpertz,

Wolfgang Mattheuer, Blinky Palermo, Sigmar Polke, A. R. Penck, Gerhard

Richter, Dieter Roth, Thomas Schütte, Werner Tübke, and others Testing and expanding conventional art terms, experimenting with new

forms, materials, and technology, and the changing status of art and the

artist all played a key role during the 1960s and 70s, the period

encompassed in the third and most complex section of the exhibition.

Revelations about the Nazi era, widely disseminated for the first time,

coincided with the burgeoning student movement as artists began to address

the trauma of the German past, break the taboo of guilt, and question

German national heroes and symbols. This was framed by an increasingly

divided Germany with the erection of the Berlin Wall in 1961. Wolf Vostell

and Joseph Beuys figured prominently, as do many of Beuys’ students,

several of whom had left East Germany for West Germany shortly after the

Berlin Wall went up. Many artists were engaged with performance activities

of the international Fluxus movement during the mid-1960s that centered in

West Germany (Nam June Paik, Beuys, and Vostell). Artists such as Georg

Baselitz, Anselm Kiefer, Markus Lüpertz, Gerhard Richter, and Wolf Vostell

in the West engaged Germany’s recent revelations from the Auschwitz Trials

in Frankfurt, while the coded critiques of Cold War politics and responses

to Germany’s recent past can be found in the work of Bernhard Heisig,

Werner Tübke, Wolfgang Mattheuer, and Hartwig Ebersbach in the East. This

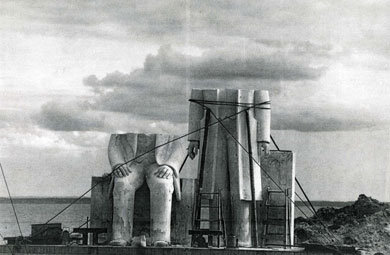

section also features The Wall (1977), a large installation of over 1,000

paintings by Thomas Schütte, the recreation of Gerhard Richter’s 1966

Volker Bradke exhibition, Sigmar Polke’s Potato House (1967), as well as

his multipart work, The Fifties (1963–69), and Dieter Roth’s Chocolate

Lion Tower (1968–69).

Section IV: The 1980s

Artists: Autoperforationists, Klaus vom Bruch, Lutz Dammbeck, Tödliche

Doris, Harun Farocki, Isa Genzken, Hans Haacke, Georg Herold, Martin

Kippenberger, Via Lewandowsky, Marcel Odenbach, Albert Oehlen, Helga

Paris, Thomas Ruff, Katharina Sieverding, Thomas Struth, Rosemarie

Trockel, and others

The fourth section of the exhibition begins with the politicization of the

visual arts as a result of growing unrest, the student movement, and the

terrorist underground during the late 1970s and 1980s. Widespread

violence, fueled in part by assassinations, kidnappings, and hijackings by

members of the Red Army Faction (RAF) in West Germany, are reflected in

photography, video, installations, and paintings of a number of artists,

including Katharina Sieverding, Lutz Dammbeck, and Klaus vom Bruch. In the

1980s, postmodern concerns of gender and sexuality, class, and race took on particular German characteristics and are reflected in the work of

Martin Kippenberger, Isa Genzken, and Rosemarie Trockel. Changing

political conditions in the East allowed the emergence of loose networks

of artists working independent of official state sanctions. The exhibition

introduces rarely seen photos, videos, and relics from the

Autoperforationists’ performances in Dresden in the 1980s, works by the

Clara Mosch Group in Karl Marx Stadt, and examples of unique artists’

books, all of which epitomize the increasing production of unofficial art.

Unofficial East German photography in the 1970s challenged state mandated

imagery; the photos of cities and ordinary citizens by Ulrich Wüst and

Helga Paris, filled with symbols, layers, and pastiche, are among the most

interesting and challenging work to emerge. This final section also

examines the synthesis of private and political spheres in art, which

undermine the Eastern state’s cultural doctrines. At the same time, topics

such as abandoned landscape and architecture offer the neutrality of

evoking the past without any direct references to politics or gender. The

exhibition closes nearly five decades after its starting point, with the

demise of the Soviet Union and the collapse of the GDR in the late 1980s.

Richter’s November and Marcel Odenbach’s video No One is Where They

Intended to Go, which includes footage of the tearing down of the Berlin

Wall on November 9, 1989, finally and fittingly frame Art of Two

Germanys/Cold War Cultures.

Upon closing at LACMA, the exhibition will travel to Germanisches

Nationalmuseum, Nürnberg (May 27–September 6, 2009), and Deutsches

Historisches Museum, Berlin (October 3, 2009–January 10, 2010).

Los Angeles County Museum of Art - LACMA

5905 Wilshire Boulevard - Los Angeles

Museum Hours and Admission: Monday, Tuesday, and Thursday, noon–8 pm; Friday, noon–9 pm;

Saturday and Sunday, 11 am–8 pm; closed Wednesday. Adults $12; students 18+ with ID and

senior citizens 62+ $8; children 17 and under are admitted free. Admission (except to

specially ticketed exhibitions) is free the second Tuesday of every month and on Target

Free Holiday Mondays. After 5 pm, every day the museum is open, LACMA’s “Pay What You Wish”

program encourages visitors to support the museum with an admission fee of their choosing.