The Jazz Century

dal 16/3/2009 al 27/6/2009

Segnalato da

16/3/2009

The Jazz Century

Quai Branly Museum, Paris

The exhibition, created by the philosopher and art critic Daniel Soutif, presents the relationship between jazz and the graphic arts chronologically throughout the entire 20th century. From painting to photography, cinema to literature, not forgetting graphic design or comics, the show pays particular attention to the development of jazz in Europe and France during the 1930s and 40s. The exhibition is organised in ten chronological sections which are linked together by a timeline: works of art, objects and documents, illustrated score sheets, records and cover sleeves, photographs, etc.

curator: Daniel Soutif

Jazz, along with the cinema and rock music, stands as one of the major artistic events of the 20th century. The sounds and rhythms of this hybrid musical style have made their mark on world culture.

The exhibition, created by the philosopher and art critic Daniel Soutif, presents the relationship between jazz and the graphic arts chronologically throughout the entire 20th century.

From painting to photography, cinema to literature, not forgetting graphic design or comics, the exhibition pays particular attention to the development of jazz in Europe and France during the 1930s and 40s.

the route of the exhibition

The exhibition is organised in ten chronological sections which are linked together by a timeline, a vertical cabinet which runs through the whole exhibition displaying works of art, objects and documents, illustrated score sheets, records and cover sleeves, photographs, etc., which directly evoke the main events in the history of jazz.

This timeline is the common thread running through the exhibition which follows the sections, themselves divided into themed rooms or rooms on one subject.

1. Before 1917

Of course it is impossible to pinpoint the exact date of the “birth” of jazz, but the year 1917 has long been considered pivotal. This year was marked by two decisive events: one was the closure of Storyville, the red-light district in New Orleans, where the famous houses of pleasure were one of the melting pots where jazz was formed (and whose disappearance would drive musicians towards the northern states in the US, to Chicago and New York in particular); the other decisive event was the recording of, if not the first jazz record then at least the first record with the word “jazz” on the sleeve (or, to be more precise, “jass”). This 78rpm record by the Original Dixieland ‘Jass’ Band had two songs: Livery Stable Blues and Dixie Jass Band One Step.

The earlier manifestations and forerunners — minstrels, gospel, cake-walk, ragtime, etc. — of the music phenomenon which was waiting in the wings to dramatically change the 20th century had inspired many artists well before this date: African-Americans, Americans like Stuart Davis or Europeans like Pablo Picasso.

2. The “Jazz Age” in America 1917-1930

The second section describes the fantastic vogue for jazz which marked American culture after the First World War. Indeed, it was so fashionable that after F. Scott Fitzgerald used the term “Jazz Age” in the title of one of his books, this would regularly be used to define the whole era, the entire generation and not just its soundtrack.

This section opens with the work by Man Ray specifically titled Jazz (1919) and gathers various other American artists or artists living in the United States such as James Blanding Sloan, Miguel Covarrubias and Jan Matulka.

The King of Jazz, John Murray Anderson’s extraordinary film about Paul Whiteman marks the end of these years, which have also been called the “wild” years, like a fireworks display.

3. Harlem Renaissance 1917-1936

One of the most noteworthy facts about this period of the Jazz Age is the blossoming of African-American culture in Harlem (but also in other big American cities) and music definitely played a major role in this.

Throughout the 1920s, under the leadership of a few eminent figures like Carl van Vechten and Winold Reiss, numerous artists (African-American or otherwise) produced a considerable amount of literary as well as visual works which often found much more than just a favourite subject in the music. This section of the exhibition is the opportunity to discover paintings, drawings and illustrations by Aaron Douglas, Archibald Motley, Palmer Hayden and Albert Alexander Smith, among others.

4. The “Jazz Age” in Europe 1917-1930

The story of how Europeans discovered the syncopated rhythms brought by the James Reese Europe’s military orchestra is quite well-known and was soon followed by shows from Harlem, and in particular the world famous “Revue Nègre” which made Josephine Baker the talk of Paris and made Paul Colin a star in the world of art posters.

From Jean Cocteau to Francis Picabia, from Kees van Dongen to Fernand Léger, the jazz bug would penetrate every aspect of culture in the Old Continent during the interwar period. In 1918, the Dadaist artist Marcel Janco called one of his important canvases “Jazz” … This section also depicts the time some of the figures of the Harlem Renaissance, such as Albert Alexander Smith, spent in Paris.

The task of illustrating this “Tumulte Noir” fell to Paul Colin who did so throughout the pages of his famous portfolio.

5. The Swing Years 1930-1939

After the Jazz Age, Swing came into fashion and large orchestras, like those of Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Benny Goodman and Glenn Miller, would get the masses dancing throughout the 1930s.

With the advent of sound in the cinema, many films bear the distinctive stamp of this era, and prestigious artists like Frantisek Kupka or the realist Thomas Hart Benton drew their inspiration from the seductive syncopated rhythms of jazz. During this period, the majority of artists who has emerged within the context of the Harlem Renaissance, like Carl van Vechten, continued their work while other African-American painters like William H. Johnson were setting out on their careers.

6. War Time 1939-1945

The Second World War made a deep impression on world culture. Music for armies and other V-Discs were on all fronts. Jazz and the influence it exerted over other artistic worlds of course could not escape the effects of this tragic war. Thus, it was during these years that Piet Mondrian, who had immigrated to New York, discovered Boogie Woogie which would have a definitive impact on his major works. In Paris at this time while the outfits worn by the “Zazous” (Zoot Suit!) — who probably got the name from Cab Calloway — demonstrated their opposition to the occupation in an ironic, albeit not very risky way, Dubuffet became drawn to the music these young people listened to and made some superb paintings and very lively drawings based on it. As regards Matisse, he created his famous Jazz in 1943 … As for American dances, the Jitterbug was now in fashion, immortalised in a magnificent series of paintings by William H. Johnson.

The end of this decade saw an event which would prove to be of fundamental importance for the future, the as-yet unknown graphic artist Alex Steinweiss created the first album cover for the Columbia…

7. Bebop 1945-1960

The end of the war coincided with the advent of Bebop, a musical revolution launched by Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonious Monk, Miles Davis and a few others. Jazz became modern.

In the world of painting, abstract expressionism, or Action Painting, was getting ready to emerge into the light of day. Some of the figures who would be the stars of this movement found their inspiration not only among the European artists living in exile in the United States during the war, but also in the jazz they listened to non-stop, as is the case with Jackson Pollock. Larry Rivers, a figurative painter but close to the spirit of this movement nonetheless, was also a saxophonist and dedicated several paintings to the music he was passionate about. Romare Bearden, the African-American figurative but undoubtedly modern artist, produced many works of art connected to the music of his community. In Europe, Nicolas de Staël dedicated some of his most important paintings to a musical style that still attracted young people in their masses… which would soon be swept away by rock music.

These post-war years would also see the growth of a new artistic field which, though minor, was fascinating: that of the record cover. Whether anonymous or famous like Andy Warhol, dozens of graphic artists devoted themselves to seducing music lovers in a 30 X 30cm format. As a mass consumer of images, this very applied art form would give some of the big names in photography, notably Lee Friedlander, a start in their brilliant careers. Other boldly specialised photographers, like Herman Leonard, would acquire quite a high level of fame through this medium.

Cinema of the 1950s were often infiltrated by modern jazz which could so easily adapt its rhythms and expressive colours to the black and white images on the screen: among the dozens of feature films, the most representative are “Ascenseur pour l’échafaud” by Louis Malle (with the music of Miles Davis) and Shadows by John Cassavetes (with the music of Charlie Mingus).

8. West Coast Jazz 1949-1960

Conventional jazz history would have us believe that Bebop was black and from New York and that West Coast Jazz grew in response to it under the shadow of the Hollywood film studios, so “fresh and refined” that some thought it effeminate. With quite a large degree of qualification, this way of seeing things is not entirely untrue. Comparing the graphic art on the sleeves of records made on both costs illustrates this opposition: blondes on sun-drenched beaches in the photographs of the west coast by William Claxton, geometric lettering and portraits of black musicians on the east coast… Many famous jazzmen from the West Coast, who were indeed mainly white, made a comfortable living composing music for Hollywood films which bear their distinctive touch… This, however, did not stop them from going to jam on Sundays in the clubs, of which Howard Rumsey’s Lighthouse would remain the most potent symbol.

9. The Free Revolution 1960-1980

In 1960 Ornette Coleman’s Free Jazz album was released. With its title that had a double meaning and a reproduction of Jackson Pollock’s White Light on the cover, it marked the dealing of a new hand: after the modern period came the free avant-garde…

This “Free revolution” was contemporary with black freedom movement— Black Power, Black Muslims, Black Panthers, etc. — and had its counterpart in the art world in the work of artists such as the stellar Bob Thompson. At this time Europe came up with its own version of Free music in the performances which were often close to the spirit of the Fluxus movement. Among the many upshots of this revolution, one can point out “Notes for an African Orestes" (Appunti per un Orestiade africana), the astonishing rough draft film where Pier Paolo Pasolini calls upon the improvisations of the free jazzman Gato Barbieri to tell the story of both Aeschylus and Africa at the same time.

10. Contemporaries 1980-2002

The visual arts began to regularly resort to using the adjective "contemporary" all through the 1960s, probably because the word “modern” no longer fit the new forms which were appearing. The term "contemporary jazz", on the other hand, has not become dated: in the “Jazz Worlds” (to use the title of a book by André Hodeir), the eras live side by side and, nowadays, they sometimes merge and blend. The exhibition gives an outline of the past two decades by highlighting the dominance of three distinct movements: the first, under the leadership of Wynton Marsalis, historicises Bebop in an almost academic way following the example of so-called classical music and regularly takes it uptown onto the distinguished stage of the Lincoln Art Center in New York; the second, with John Zorn at the forefront, pursues and develops the libertarian and avant-garde tradition inherited from Free and which settled Downtown in the small, independent clubs where Jewish composers are often celebrated — Great Jewish Music, is the title of a series of records by Zorn with a notable tribute album to Serge Gainsbourg; the third is, to put it simply, the rest of the world and Europe in particular where many very talented musicians demonstrate the universality of jazz and its multiple descendants which do no more than merely reference the American model.

Moreover, jazz’s presence in contemporary art remains considerable as demonstrated by the many pictures imbued with Black Music painted by Jean-Michel Basquiat over the course of his brief career, videos by Adrian Piper or Lorna Simpson, or even that admirable photograph by Jeff Wall inspired by the prologue to Ralph Ellison’s The Invisible Man.

Enitled Chasing the Blue Train, the large installation made in 1989 by legendary African-American artist David Hammons - with its small toy train running non-stop, its piles of coal and its piano lids standing on their sides - provides the entire exhibition with the following conclusion: if the 20th century, this jazz century, is well and truly over, the train of the music which accompanied it perhaps more than any other, will always be in motion.

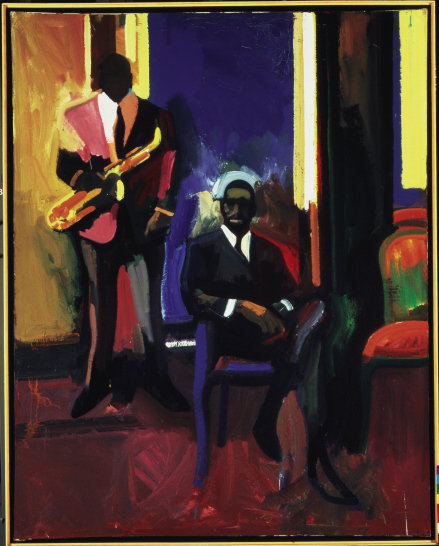

Image: James Weeks, Two Musicians © San Francisco, Museum of Art

Co-production

This exhibition has been co-produced by the Mart – Museo d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto, the musée du quai Branly, Paris and the Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona

Musee du Quai Branly

37, quai Branly 75007 – Paris

tuesday, wednesday and sunday : 11am . 7pm

thursday, friday, saturday : 11am . 9pm